My family lived at the top of a mostly wooded hill in a little town in Connecticut, about an hour and a half from Stevens’s Hartford. Some 80 acres of mixed deciduous woods stretched behind our house and lots more forested watershed-conservation land surrounded it—beyond our biggest spruce, across the road, and all down the steepish hill to the reservoir, a wide lake whose water was meant for Bridgeport or somewhere. (Ours came from a well.) A strange moony sort of girl, when not in school or riding the bus to and from, I mostly read novels or tramped around in those woods.

I don’t think I ever felt I needed permission to write poems. Year in, year out, well meaning teachers encouraged us all to write little ditties, haikus, and pretty rhyming things and—don’t get me wrong—I enjoyed the task and could usually rack up a “+” or an “A” for my efforts. But one day Mr. Concilio, mild-mannered 9th grade English teacher (and it turned out something of a poetry Superman) changed for me what “poem” meant when he handed out a mimeograph sheet, still damp and smelling deliciously of probably toxic purplish ink. He’d managed to fit both Wallace Stevens’s “The Snow Man” and Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Pied Beauty” on one page.

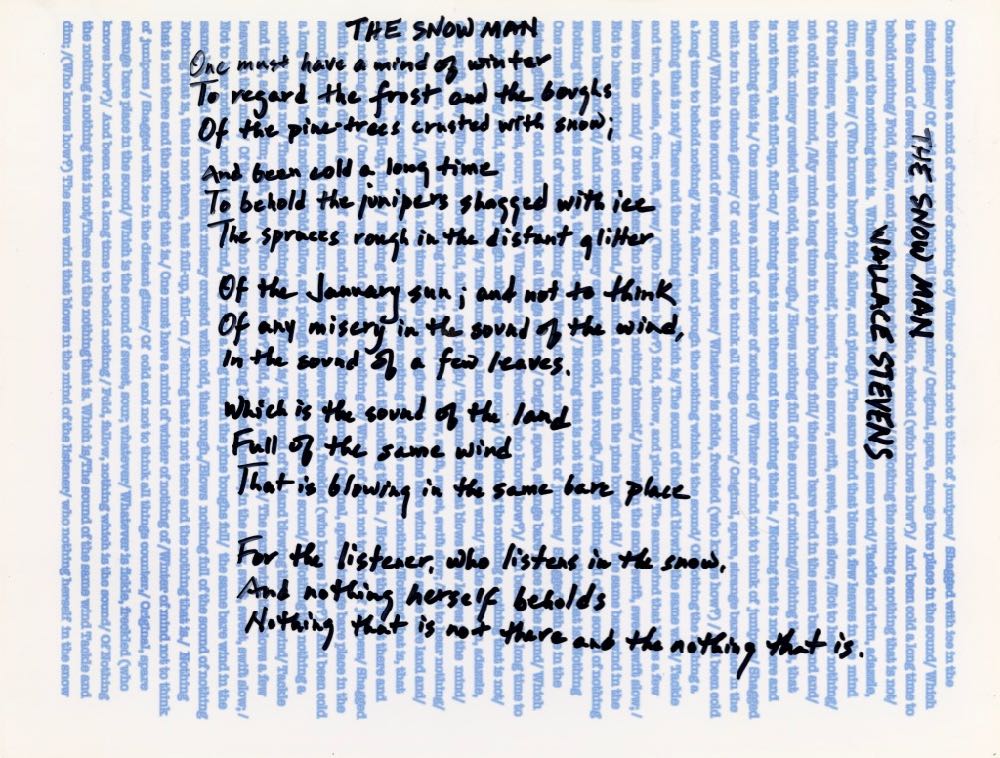

He probably introduced the poems with something about unusual words and whether we knew what juniper and pied meant. But I wasn’t listening. I was reading: “One must have a mind of winter… junipers shagged with ice … rough in the distant glitter,” and wondering what it felt like to be cold so long that your mind turned wintery and you felt like a snowman. I was repeating silently to myself over and over that mysterious, solemn, slow last line. “The nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” Nothing and nothing at the far-end of a long sentence and an un-foot-printed walk through the snow.

And then I was on to the next tiny poem on the handout. It started out familiarly, too, if in a different way. It started out rather like the many “What I Love About ____” poems I’d been writing since 1st grade, except that it leapt quick into music I’d never heard anywhere before: “Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings… swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim…”

Intoxicated by the blurry blue words on the page, I lost track of everything else for awhile, even my adolescent self-loathing. I was head over heels in love. The combination of Stevens’s stately rhythms and mysterious distant glitter with Hopkins’s word-crazed, jerky, dazzling music didn’t give me permission to write—it gave me a reason to want to.