After a year of college, I knew I was not going to major in Classics (early class times), Political Science (dry texts), or Philosophy (huh?), so I signed up for a course called Contemporary American Poetry. We met in the afternoon, in a classroom dominated by a wood table that had been worn by age into a dark honey. It was shaped like a pond, a near ellipse, and how it got into the room was unfathomable to me. As the professor spoke, I would wonder how many lengths of my body it would take to reach the other side and then realize that everyone sitting around the table was paying more attention than I was.

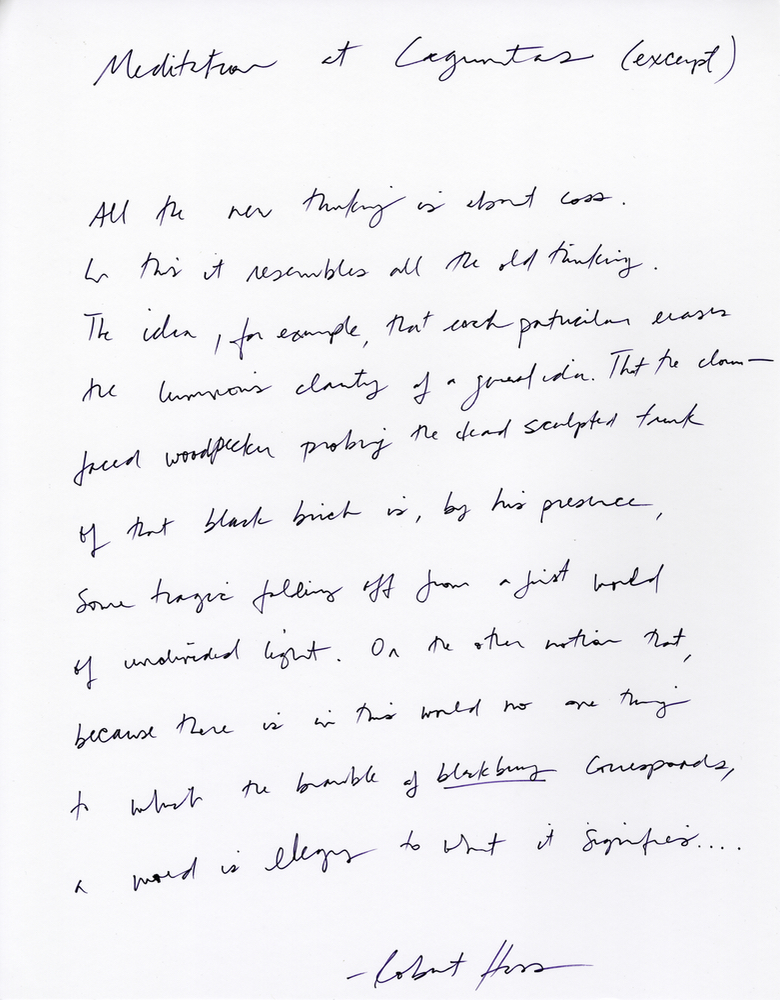

Professor Von Hallberg—whom we’d come to know as Bob—had a deep sonorous voice, one that sauntered as he read, as if he were wandering the coastline of his native California instead of standing solemnly in a cold seminar room at the University of Chicago. After he’d read a poem, his voice would, for a moment, linger in the air, a cloud of thought and feeling, and then he’d switch register, pitch gently rising, to ask us a question. Why didn’t I listen more carefully, and sooner? For, one day, after weeks of my daydreaming, he directed us to turn in our anthologies to the section on Robert Hass, and then he recited the poem “Meditation at Lagunitas.”

Even now, some twenty years later, there are two turns in “Meditation at Lagunitas” that I still hear in Bob’s voice. “[A] word is elegy to what it signifies,” the culminating observation to Hass’s opening images, a series of particularities that seem to sharpen the language. The second turn: “But I remember so much, the way her hands dismantled bread.” Here Hass begins to doubt that language should precipitate loss, or that loss alone informs our linguistic impulses. What about the memory and feeling that never leave? The private history of a word that remains, remaking us and that word? With the utterance of each line, I swore I heard a tender catch in Bob’s voice. Or rather, I was hearing the voice Hass constructs, the speaking subject reaching out to the reader for something that feels like intimacy.

The thing is, that day I hadn’t done my homework, had not done the reading, and my professor’s recitation was my first encounter with this poem, and so that final line startled me into revelation. I did not know that a single word could be uttered repeatedly and produce a different meaning—feeling!—each time: “blackberry, blackberry, blackberry.” Even now, the word, spoken thrice, sits on the page and in the air around me, shimmering with secret knowledge, the past and the losses of the past, shimmering with the ritual of naming which can make some poems seem unexpectedly sacred.