Were it not for the epigraph a reader could hardly guess that “In Memoriam” honors a devastating public tragedy, the 1968 assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. In this, poet Wong May eschews the conventions of elegy, offering neither a lamentation nor a language by which we might mourn this particular collective loss. Instead, there is circumvention, the world in which the loss happens, loss elided by springtime, parties, and the bleak disorderliness of ordinary life. The poem begins in media res and with the conjunction of connection—“And if you come to my party / I will come to yours”—and then the poet effervesces: “There will always be parties / and poetry.” Such is the “human position,” to cite Auden, our greatest theoretician of public poetry, “how it takes place / While someone is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.”

On April 3, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his final speech, “I Have Been to the Mountaintop,” in Memphis, Tennessee. The next day James Earl Ray aimed his rifle at King, who stood on the balcony adjoining his room at the Lorraine Motel. King would not survive the shooting, and it’s arguable that the country did not survive (has it survived yet?), as cities erupted into violent race riots in the days following.

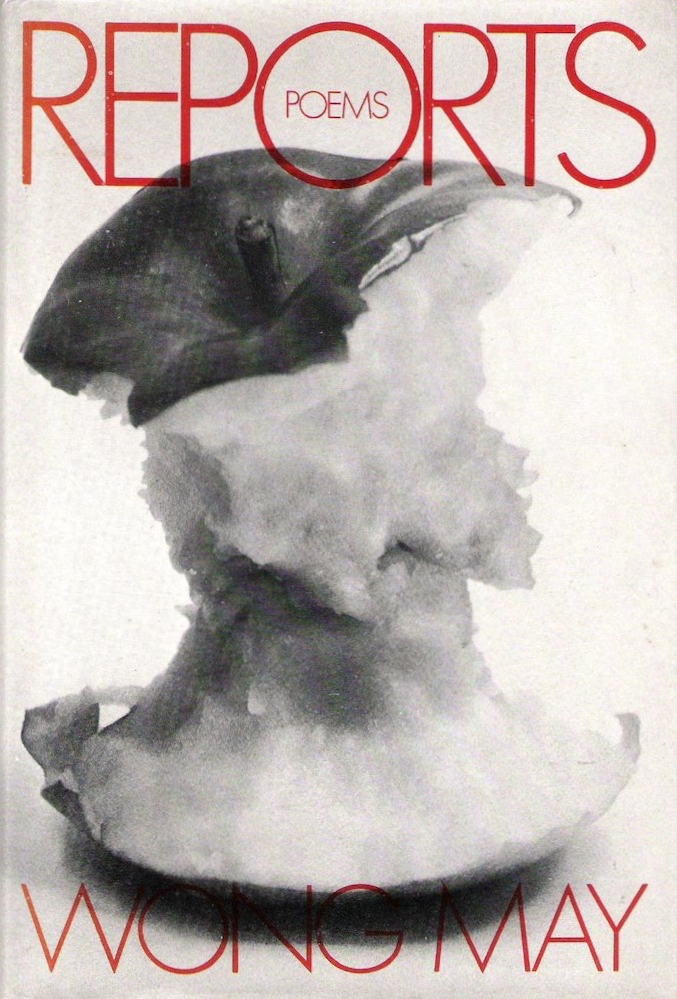

And where was Wong May? She had arrived in the United States from Singapore in 1966 to attend the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and then spent time in New York City and at The MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, but she was also, like many young poets, peripatetic, traveling to Europe and Asia until finally settling in Ireland in 1978. Nevertheless, living in the United States during the social unrest of the late 1960s no doubt informs the anxious sociocultural dynamics of “In Memoriam” and numerous other poems from Reports, the out-of-print second book in which “In Memoriam” appears.

One of the secrets of public life is that, despite the public record, people of color were indeed out and about. In public. They were at the parties, asking questions (“What is the occasion?”), watching, listening, immersed in spring and the quandary that is American freedom. Remarkably, “In Memoriam” exposes this secret. When I first encountered the poem several years ago, what stood out first to me was that an Asian poet was writing a contemporaneous poem about a defining tragedy of modern American history. “In Memoriam” documents the intersectionality of grief. It determines the distance between marginalized perspectives, between elation and devastation, as no greater than an enjambed line. Consider the resonances between the poem and the slain minister’s final speech:

“The nation is sick,” King proclaims, “Trouble is in the land; confusion all around. That’s a strange statement. But I know, somehow, that only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.”

If Wong May seems to refute this diagnosis, her use of repetition performs a collective denial, the fear that precedes great cataclysmic change:

Listen: I am not sick

You are not sick

the in-patients are indoors

the out-patients are outdoors

the world is not sick

The ensuing martinis cannot erase the prospect of blood or that “Assassins spring up everywhere like prophets.” As a reader, I long for more prophecies in poetry and in life, Wong May’s and Dr. King’s, who in that same speech declares, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now.”

In “In Memoriam,” after so much listening, the speaker finally hears nothing, and that is the silence loss grants us, what might be misread as peace or “catkins falling off willow trees.” No, silence is unintelligible. The memories of “In Memoriam” are fleeting, almost trivial, almost ironic; they signify the limitations of elegy, that there is no honoring a loss that should not have happened. It is a lie, then, that “the world is not sick.” Perhaps what’s public here is the unspeakable, beyond comprehension, unbearable, what no exegesis could ever adequately make clear.