The mind of the state is pure paperwork, a complex network of ledgers, lists, reports, and correspondence. With its deep cache of data and document, the state could remember almost anything, but what it chooses to remember often reflects only its tremendous narcissism, its investment in perpetuating carefully chosen images of itself. These days it seems the state will remember almost nothing outside of the oft-told stories that justify its continued rule; it calls upon its powerful, vast, and highly detailed memory mostly to reinforce narratives that continue to consolidate and reify its own power. And yet, as Natalie Harkin’s Archival Poetics powerfully reminds us, the mind of the state can be made to remember what it’s strategically chosen to forget.

A self-described “Narungga woman and activist-poet from South Australia,” Harkin delves into Aboriginal Affairs records in an attempt to decolonize its archives, to take back from the state the traces of ancestral voices and lives it has stolen. Harkin’s work casts “a small spotlight on the state, its institutions/ systems/ processes, that generate particular fantasy-discourses and representations on histories, on people: that actively silence/ suppress/ exclude indigenous voice and agency.” Her research proves the state in fact remembers the smallest bureaucratic details of white supremacist policies designed to carefully and relentlessly subjugate and surveil indigenous people. Her poems, photographs, and sculptures literally wrest language from the state in order to tell stories that its archons first meticulously record and then later suppress and “forget.”

In using the state’s archive against itself, in forcing the state to remember its many forms of violence against indigenous people, in releasing ancestral voices from their archival confines, Harkin counters oppression with “infinite ways to imagine/ infinite possibilities to/ transform/ beyond this colonial-archive-box.” Her inventive and necessary interventions into Aboriginal Affairs records offer back to the state its own language not as a narcissistic exercise in nation-building but rather as an indictment of its alleged successes: first, at colonization, and then, at suppressing both its own memories of violence and the voice, memory, and agency of indigenous people.

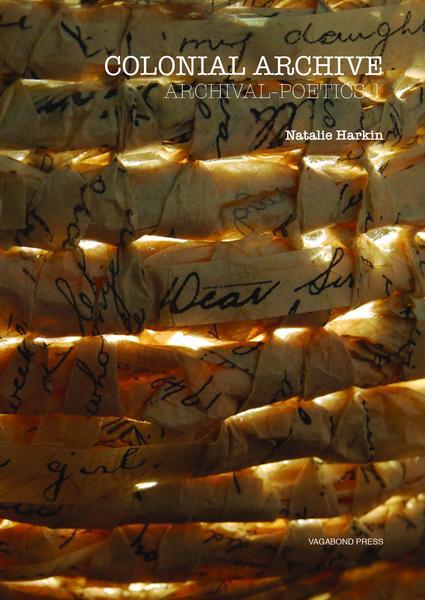

In the moving texts “A Basket to Haunt” and “I Weave Back to You,” Harkin details the process of literally reclaiming the words of “our grandmothers” from the archives in which they’ve been trapped. The accompanying photos document how she separates out their words from those of the archons, tearing and shredding before ultimately weaving a basket that can both “carry the load a bit lightly” and “haunt.” Taken together, Harkin’s decolonizing texts and images make the state do the work of incriminating itself, its meticulous memory offering damning and ample evidence of its crimes. With each phrase torn out of and reclaimed from the state’s papers, Harkin releases and weaves stolen words back into indigenous memory.