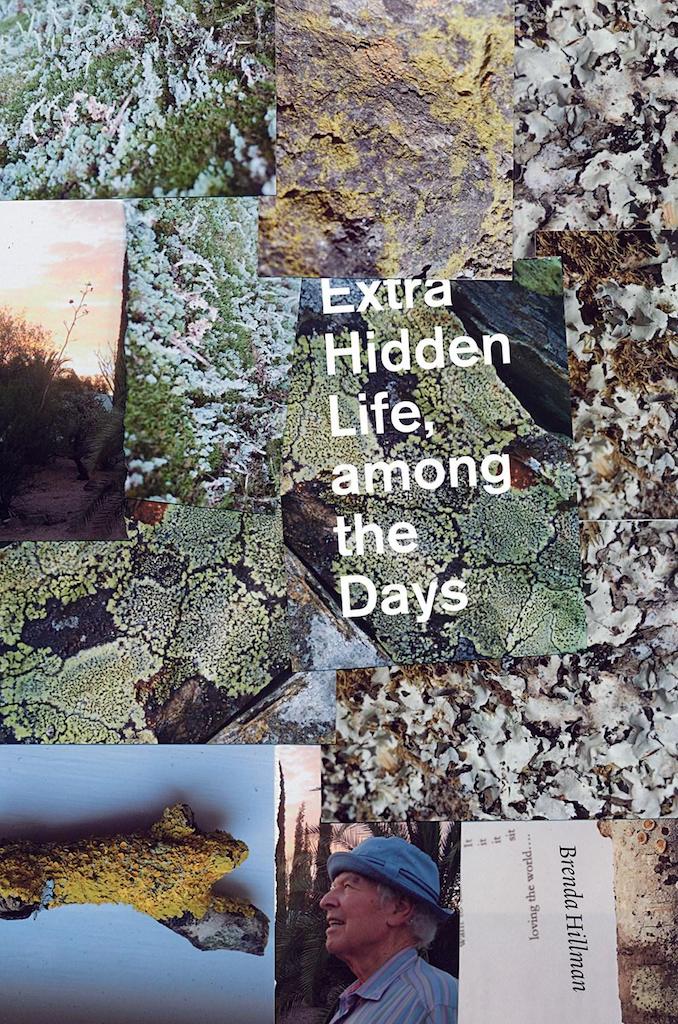

Brenda Hillman’s “Angrily Standing Outside in the Wind” begins with the witty opening gambit: “—kept losing self control / but how could one lose the self / after reading so much literary theory?” Recently, while reading Hillman’s Extra Hidden Life, among the Days and preparing to teach my own critical theory class, I discovered the work of new media artist Jacolby Satterwhite. In an Art21 segment “Jacolby Satterwhite Dances with His Self,” the artist layers drawing, video, and 3D animation, featuring multiple simultaneous images of himself, dancing, voguing, or just climbing into the frame. Satterwhite states: “Social media, technology, the Internet, and the way that our bodies exist virtually: it’s a paradigm shift for the multiplicity of the body. My body is multiplied several times in my videos.”

Satterwhite’s work, the way it makes a complex interiority public, partly through the proliferation of the artist’s own image, immediately brought to mind Hillman’s poem, in which—instead of Satterwhite’s “unlimited sci-fi surrealist paradise”—a subtle conflation of exterior reality and interior landscape become a space where the wild or sur-rational parts of the self can reach for expression. In Hillman’s landscape, littered with “doubt debris,” “clouds” move above the trees like “the bones of a Kleenex.”

The first line of the poem, “—kept losing self control,” exposes one danger of being in public, the danger of losing control. But is it in our best interest, or even rational, to demonstrate control over ourselves, our emotions, in the face of fascism or environmental collapse? What is the use of self control, the poem asks, as the speaker’s persona fractures on the page.

There is no “I” outside of quotation marks in this poem. The title omits a subject entirely, and in the body of the poem, itself (un)bounded by dashes that gesture toward an unlimited space, we find the “shorter ‘i’ stood under the cork trees” while “the taller ‘I’ remained rather passive,” and then, most surprisingly, “the Brendas were angry at the greed, angry / that the trees would die.” Like Satterwhite’s selves multiply in grief, joy, or desire in his evocative video work, the poem’s titular “anger” creates a pressure under which identity stutters across reality.

And what about the wind? The wind is “soughing” through the poem’s landscape, and the word “soughing” itself begins to enact the wind’s passage through the scene, appearing as a fresh gust each time. Though it’s most often pronounced to rhyme with “cowing,” it can also be pronounced, in British English, to rhyme with “huffing.” I hear the wind “suffing” and puffing, wind of change, a chilling “Weltgeist,” world-spirit, world-ghost haunting all of us as we weigh whether it is or is not, after all, “too late for trees.”

The poem abandons syntactic control in its final stanza, as phrases remix and repeat, and the “wind with its sound sash” deranges the awful, aforementioned “gaps between can’t and won’t.” Jacolby Satterwhite says of his artistic persona: “the body that I’m performing as doesn’t understand limits.” Hillman’s personae stand, likewise, vulnerable and powerful presences at the vortices of seemingly unlimited forces—climate crisis, hypocrisy of the powerful, philosophy, and emotion, to name a few—herselves “increasing bold.”