This was fourth grade, maybe fifth, when everyone I knew I knew by full name. Forrest Norman. Carlton Hickok. Mike Heenan. Carol Blosser. Mika Sam. I recall the names, but few details. Each classroom was the same as the last. One day’s ignominies slid into the next.

When I try to recall myself as a kid, I rarely see myself in the world. I see everything I could not understand swirling around me, like some isolated star whose gravity draws to it a unique set of confusions & terrors.

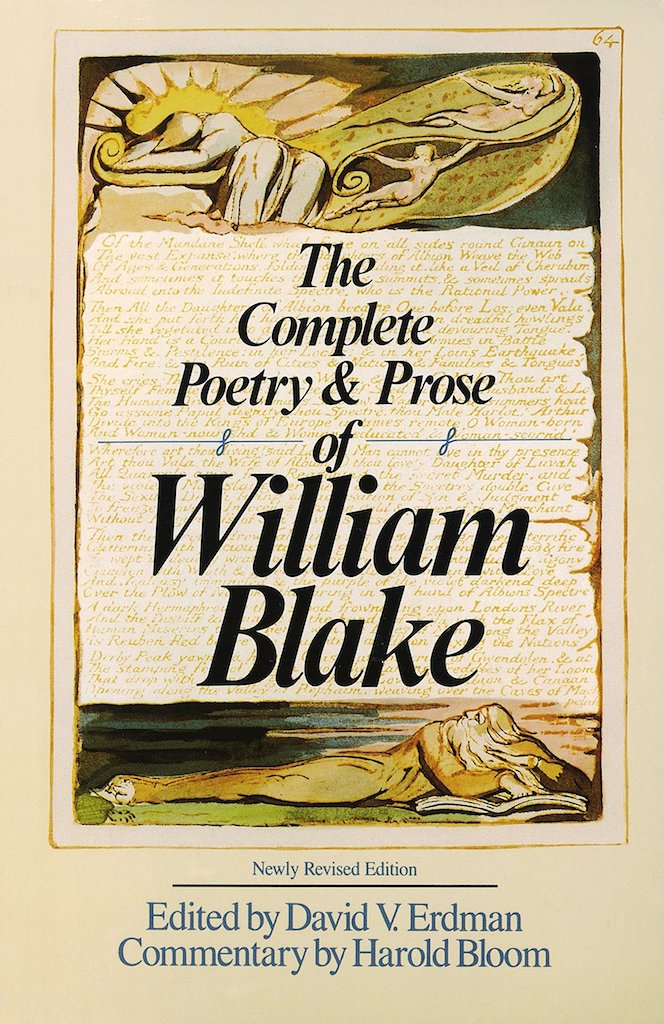

But I do recall myself reading this: “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, In the forests of the night; What immortal hand or eye, Could frame thy fearful symme… tri.”

When I read this the first time, my mind buzzed. I recall the buzzing.

The effects of those lines seem parsable now, now that I know a bunch of stuff about poetry: how the rigid trochees march lock-step into semantic & sonic failure; how the “try” in “symmetry” visually makes a rhyme with “eye” but refuses to fully work, thereby working more; how words pound; how words mean more than meaning; how words both desire & refute confinement; how the mind & the tongue can be controlled & can be liberated; how we can, as words sometimes do, sneak into transcendence; how we each have the chance to escape terror’s murderous gravities.

I didn’t know this stuff in fourth grade, or fifth, obviously. I just knew the buzz. I knew this little poem in a little textbook in a little classroom in a little school in a little suburb in a little state in a little country in a little world was somehow very very very big. I read the poem again & again. I read it in class. I read it at home. Some nearly forty years later that poem can still bebuzz me.

It was my first run-in, I guess, with that feeling that each railroad tie & cracked glass & dead leaf & fluorescent light & Carlton Hickok & insect & blue whale & grubby desktop is there because I am there. And vice versa. And also not. And also so much more, a more that words can’t behold. My first run-in with what the mystics bank on, that the world is little & the self is big.

It was maybe perhaps somewhat similar to how those unsuspecting test subjects dosed by the CIA with LSD might have felt. The visionary rising up unbidden. Maybe my dedication to poetry, a vocation I have never been able to justify admirably, this desire to manufacture transcendences out of words, is just chasing this first high of visionary realization & its predicating brain chemistry.

But also, it’s true. One moment you can be a child in a classroom, terrified & trapped, & then you read the right words, & you are free. It’s true. Freedom is real. Art is true. And once you know a true thing, it is difficult to un-know.

I don’t read a lot of Blake these days. Sometimes reading his stuff can feel like listening to The Doors. Though it is more likely that my soul no longer has the stamina for what his work demands. But when I run into Blake’s poems, especially the short stuff, it’s always a good encounter, a bit like when a Jodeci song comes on at the bar & I sing along, a bit like standing at the edge of a tall cliff as the nerves in my legs light up & I salivate.

And maybe what I’ve come to appreciate most about recalling that moment of reading Blake’s “The Tyger” for the first time, of getting a poem for the first time, of getting a work of art for the first time, is that it is one of the rare moments that I can look into my memory & see someone I recognize as being me.