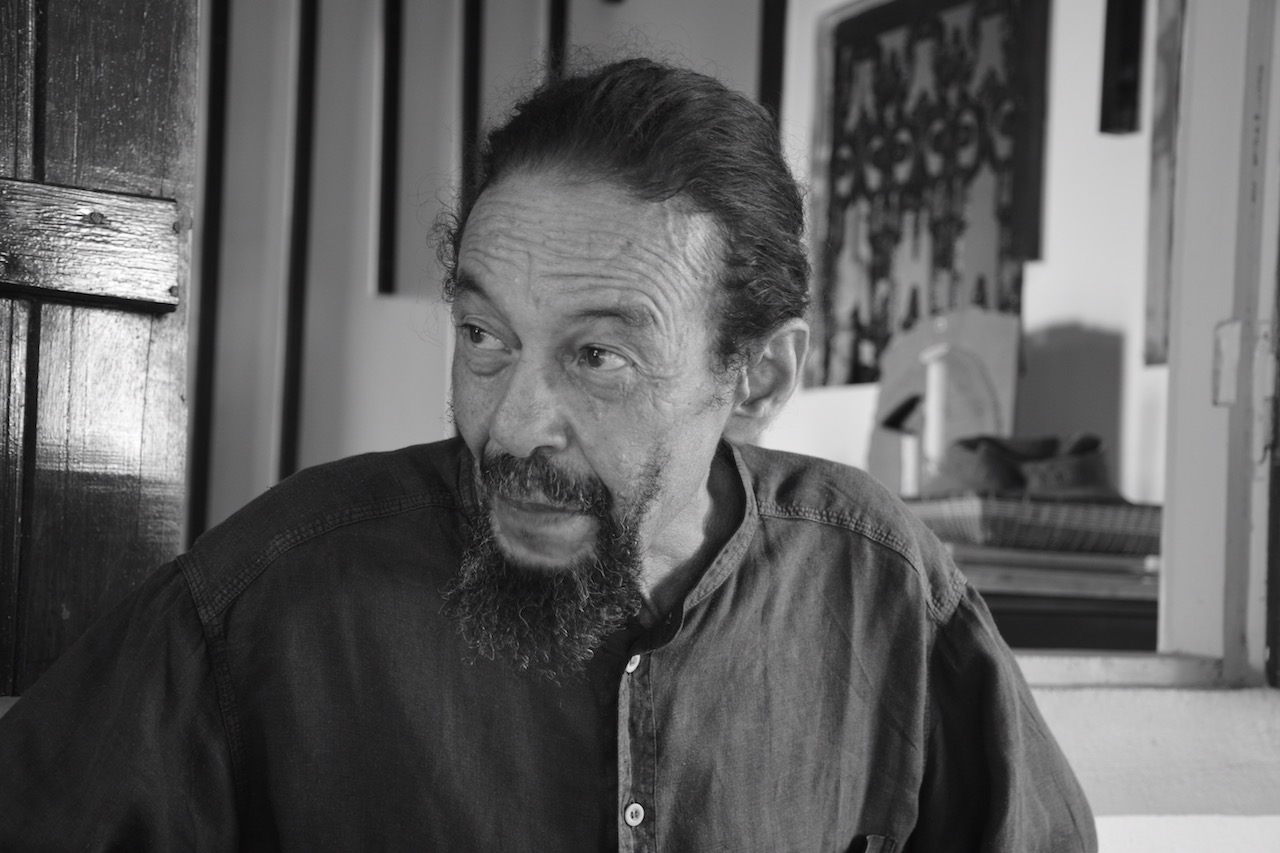

The poet, like the Indian, ear glued to the ground. He perceives what has happened—and resonates still—and what is coming.

He comes, overwhelmed, from the fallow colors of the dry season.

He hears Creole coming from Creole throats (rare and moving).

He notes the singular way in which we stare at one another.

Geography’s an act of “indicating.” A figure. Like all writing, it’s first of all marking, an imprint made through walking.

What is more catastrophic than writing and the earth?

*

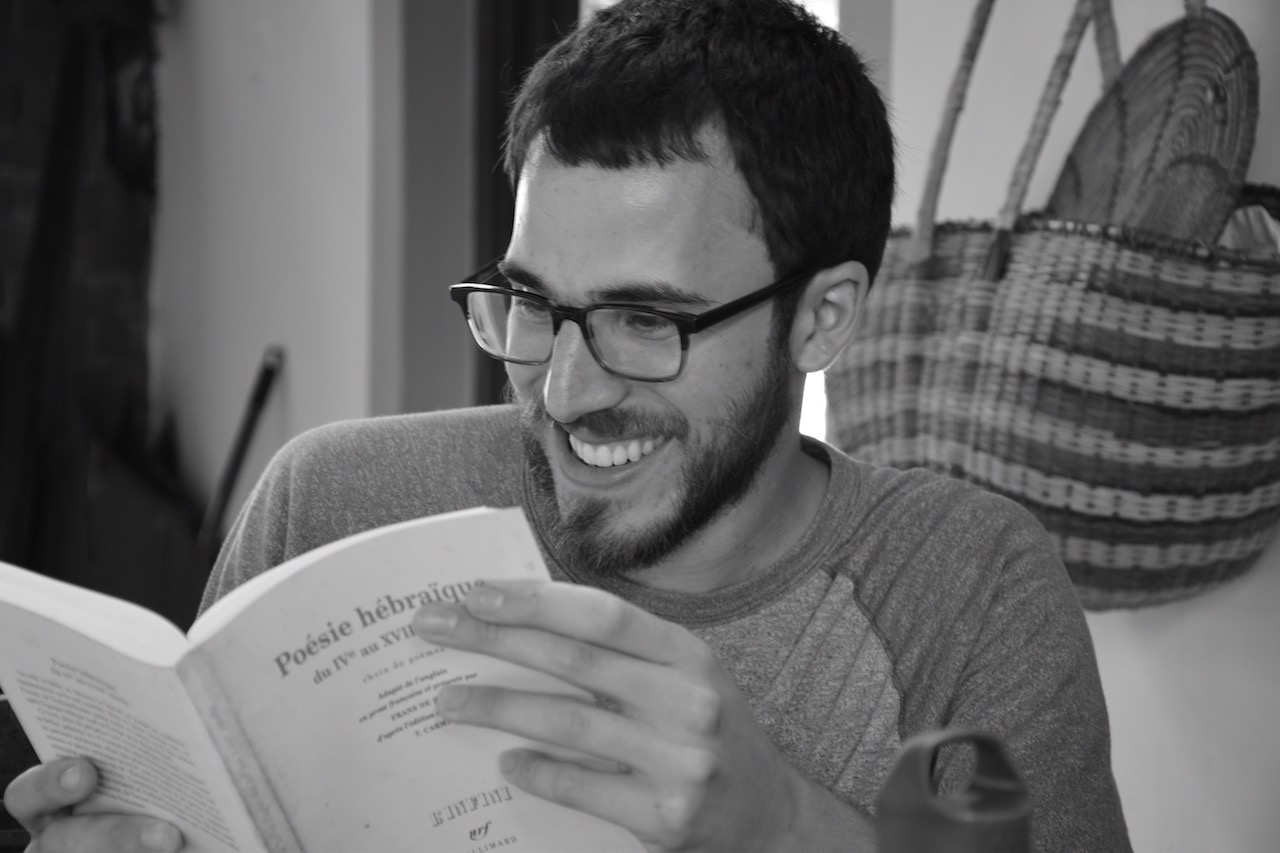

For us, the passage from Creole to French and vice versa is a subtle art, similar to footwork in soccer: to alternate between elegance, social decorum, and the pure pleasure of words, of speech in your mouth. The main art lies in the conjugation, to make sure it assuredly shimmers.

There are muffled places where your instinct would be to force your voice. In the Caribbean, due to the frequently chaotic topography (from hill to hill) and scattered geography (from island to island) we’re used to the leap. We’ve adopted the habit of calling out for each other.

This leaping topography and geography (from hill to hill, and from island to island) has its echo in Creole in the way forms are multiplied: di i di sa / mennen pou mennen-y alé / ralé menm i ka ralé-y. Heritage of the Caribs’ language.

The poet sees the islands (“yes, they are many, the islands, and beautiful”) like a text whose consonants would be but boulders on which to place his foot before springing into the open sky and sea, as in these Carib words:

bonambaé — kabonakati — amalaka.

“That he bursts in his leap through what cannot be imagined or named . . . ”

*

Eti jou ka kouri ouvè kon an wélélé.

The day arrives like a quarrel. Such a tangle of lovers that came together in the dream. Like the kingbirds you sometimes see collide mid-flight, in a great flutter of wings. And they part so forcefully that they leave a shimmer in our eyes, a piece of white sky.

*

The Caribbean could be considered a workshop for the modern world: with its deportations, its exterminations, and also its “wildly multiple” side, its “ubiquity of voices and sounds.” Its diphthong.

“For sale . . .

reassembled voices … the only chance to free

our senses!

For sale priceless bodies ( . . . )

For sale applications of computation and unimaginable

leaps of harmony ( . . .)

For sale bodies, voices . . .”

*

Full moon. The clouds make us remember our wanderings. Our escapes. Like the archipelago in its deployment: the poem.

Where is the Caribbean? What is its place?

“This world of dew

is a world of dew

and yet, and yet . . .”

“You must hurry.

History will close.”

The hut where the moon stays opens the time of the day before.

La case où se tient la lune

Le poète, comme l’Indien, l’oreille tendue collée au sol. Il perçoit ce qui a eu lieu et résonne encore et ce qui vient.

Il vient des couleurs fauves de Carême à s’affoler.

Il entend parler créole dans un gosier créole (ce qui est rare et émouvant).

Il note cette singulière manière que nous avons de nous dévisager.

La géographie est un « montrer ». Elle est figure. Comme toute écriture, elle est d’abord marquage, empreinte faite en marchant.

Qu’y a t-il de plus catastrophique que l’écriture et la terre ?

*

Chez nous, le passage du créole au français et vice versa comme un art subtil qui s’apparente au jeu de jambes au football : il fait alterner une manière de distinction et de convenance sociales avec le pur plaisir du mot et de la parole dans la bouche. Le grand art est dans la conjugaison, et d’y laisser paraître certain chatoiement.

Il y a comme cela des lieux sourds où la tendance naturelle est de forcer la voix. En Caraïbe, du fait d’un relief souvent chaotique (de morne en morne) et d’une géographie éparse (d’île en île) nous nous sommes accoutumés au saut. Nous avons pris l’habitude ici de nous héler.

Ce relief et cette géographie bondissants (de morne en morne, et d’île en île), il en perçoit l’écho en créole dans la forme de la réduplication : di i di sa / mennen pou mennen-y alé / ralé menm i ka ralé-y. Héritage de la langue des Caraïbes.

Le poète voit les îles (« oui, elles étaient nombreuses, les îles, et belles ») comme un texte dans lequel les consonnes ne seraient que des rochers où simplement poser le pied pour bondir dans l’ouvert du ciel et de la mer comme dans ces mots caraïbes :

bonambaé — kabonakati — amalaka.

« Qu’il crève dans son bondissement par les choses inouïes et innommables … »

*

Eti jou ka kouri ouvè kon an wélélé.

Le jour s’y lève comme une querelle. Tel un démêlé d’amants qui a pris souche dans le songe. Comme ces oiseux pipiris qu’on y voit parfois se heurter en plein vol, dans un grand battement d’ailes. Et ils se départissent si vivement qu’ils nous laissent dans les yeux un scintillement un grand morceau de ciel blanc.

*

La Caraïbe peut être perçue comme un atelier du monde moderne : avec ses déportations, ses exterminations, et puis aussi son côté « désordonnément multiple”, son « ubiquité par les voix et par les sons ». Sa diphtongue.

« À vendre …

les voix reconstituées … l’occasion, unique, de

dégager nos sens !

À vendre les corps sans prix …

À vendre les applications de calcul et les sauts d’harmonie inouïs …

À vendre les corps, les voix … »

*

Pleine lune. Les nuages nous font souvenir de nos vagabondages. De nos échappées. Comme l’archipel dans son déploiement, le poème.

Où se teint la Caraïbe ? Quel est son lieu ?

« Ce monde, une rosée,

Je le veux bien :

Pourtant, pourtant … »

« Il faut se hâter

L’Histoire va fermer. »

La case où se tient la lune ouvre le temps de la veille.