When I think about “objects” and poetry, I’m immediately reminded of the powerful influence upon me of the English translations of Rilke’s “thing” poems such as “Archaic Torso of Apollo” and “The Panther.” The power of these poems, it strikes me, is less in their rendering of a physical object, placing it before the visual imagination (though Rilke’s poems certainly achieve that), than in their unique energy and movement, their centrifugal force, that power to carry away the reader, as Rilke writes in the torso poem, “from all the borders of itself,” and “ to burst like a star,” the poem ending with one of the most well-known and astonishing lines in all of poetry, “you must change your life.”

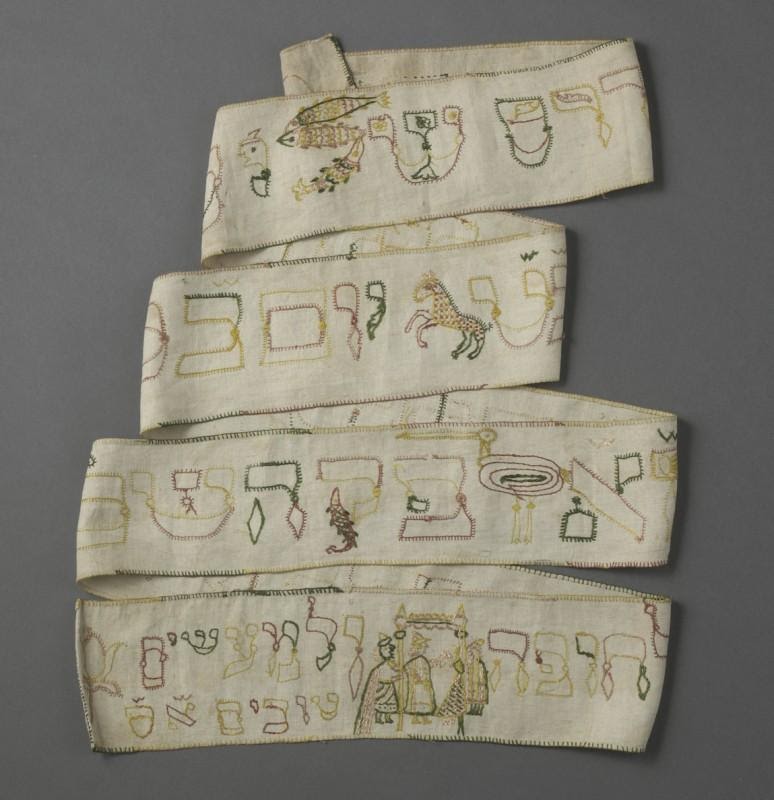

The “bandelette de Torah” is the embroidered ceremonial cloth wrapped around the sacred scrolls when stored in their cabinet. During a synagogue service, when the Torah is placed on the bimah or podium, the bandelette covers and protects the unscrolled portions of the sacred text. When the text is to be read, the cloth is lifted to expose the scripture for oration.

When I first saw the bandelette in the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, in Paris’s Marais district, I immediately experienced one of those Rilkean “bursts,” for here was an object, that in its ornate yet near-transparent being, invoked so much of the social, cultural and historic struggles of the Jews which are writ large across and infuse the whole of Western culture from earliest times through the rise of Christianity and the Church fathers, on up to the Shoah. At the time of composition, I was reading Gillian Rose’s Mourning Becomes the Law, a book, that with sharp intelligence, ranges over themes of power and domination, transcendence and eternity, poetry, the Holocaust and Judaism. And, in a way, it was her thought that left me ripe and open for the associative feast that the bandelette represented.

Even more “symbolic,” was that, in its daily use, the bandelette lies in the in-between, in the border that both joins and separates, as borders do, the sacred text and the profane world. This nexus or gathering point, with its many currents, seemed to demand some kind of articulation. And, in an almost required dictation, I wrote them down as they came to me.

The richness of the bandelette’s associations have stayed with me, as did my continual thinking about its symbolic use, which in some way seems inexhaustible. Some years after composing the poem, I wrote another entitled “Mappah,” the Hebrew name for the bandelette, which takes as its point of imagery the burning of Torahs and their ceremonial wrappings in the Shoah, and sees the smoke and ash as a warning, “a wish to call out.”

Like the bandelette, the poem, for me, has always been the object “in-between,” the words that form a pathway between poet and world. And in that sense, the bandelette can also symbolize the idea of poetry and poem-making as “the word between us,” “words” as richly figured “burls in woven cloth.” In Paris, in that old hotel particulier in which the museum was housed, the histories and traditions I had been raised in swirled around me.