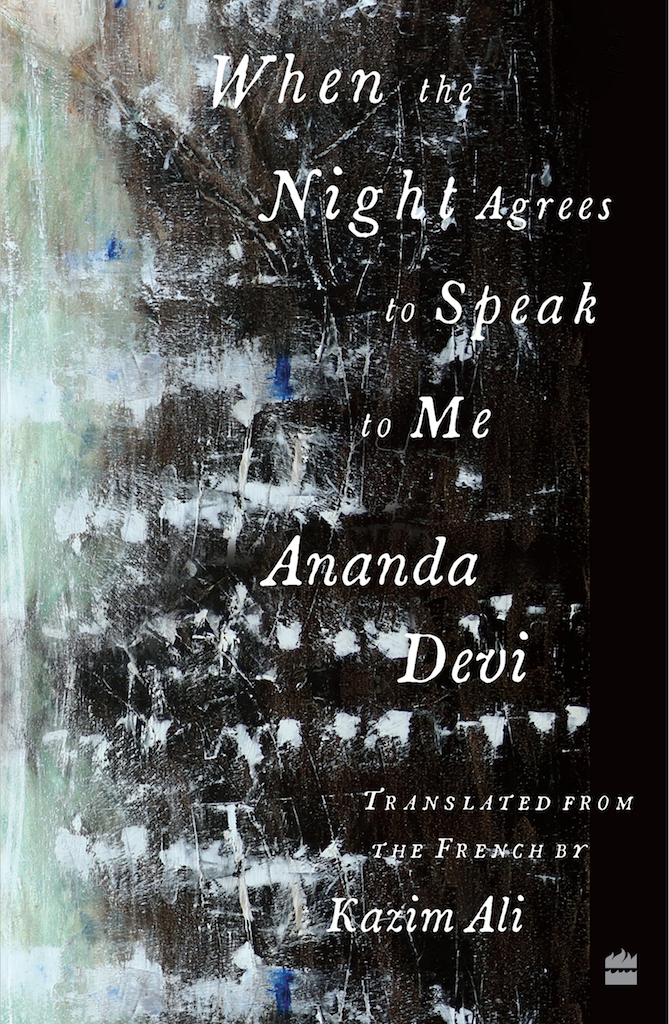

Strangeness is what drew me to translating Ananda Devi’s poetry. I was in France when I first saw her book Quand la nuit consent à me parler on a table in the poetry section of Gibert Joseph. It was small chapbook-sized collection in hot pink with bright yellow letters. A long title poem in thirty small sections with three short prose pieces at the end. Something about the size was appealing; I like short poems, I like tight collection. I took the book home and began reading it.

My French is home-taught. I learned it by reading and listening and fumbling through trying to socialize with my Parisian cousins (whose father is Indian and mother is French). I learned it by sound—for example eventually I figured out that if I heard “va” it meant something was happening in the future and if I heard “a” something was happening in the past. Because the French I learned was mostly verbal and aural, I never learned tenses, never learned how things were spelled. Frankly, it’s an easy way to learn French. I went from kindergarten level to going to poetry readings and academic lectures in about a month and a half. I’m not saying I understood everything but I more than got by.

Of course. Technical problem. Duras I could actually read in the French without needing much help in the way of a dictionary or a native speaker to help me, but Devi was another level. Not only was her vocabulary much more complex, she also used sound, image, and metaphor in a dense and allusive manner. I could read the book with difficulty (and the occasional side-track to Robert & Collins), but it was slow, slow going. That winter I flew from Paris to Chennai to take part in a literary festival and after it was over I planned a trip to Kerala. While in Chennai, the driver—quite an accommodating festival! I had a driver—took me down to Pondicherry one day.

I strolled the (smallish) French Quarter and spent a grand afternoon at one of the cafes. The Quarter is right on the ocean—there’s nearly no beach—a wall of boulders stacked high against the tide and waves thundering against them. It was there that I realized—the sound of French being spoken by South Asian people, a phenomenon I had not until then experienced—that the French was a South Asian language. I know it’s ridiculous that it took me leaving Metropolitan France where I had been reading a book in French by a writer of Indian descent, but somehow, there next to the ocean, the sun beating down and the sea wind blowing in, it really sunk in.

I had a notebook but no dictionary. I just worked up word-for-word glosses, bracketing and leaving in French any word I didn’t know. A week or two later, in the cliff-town of Varkala, in another cafe, looking over the brilliant Arabian Sea, this time an old battered paperback dictionary I’d scared up by my side, I began again with the poems and prose in the book.

Writing Devi’s poems into English—I guess I mostly believe that Benjamin was right: even the original poem is a ‘translation’ of an experience past language—made me a writer of poems nothing like the poems I myself wrote. They were poems of great despair, of great rage, emotions ordinarily thought of perhaps as ‘negative;’ certainly they were emotions and feelings that I myself was only just beginning to explore in my own work.

Yet at the same time, the spare and elegant way Devi had with French—for example her “les mots meure un lent mort” has an assonance that “words die a slow death” can never have—just seemed impossible to achieve in English. Sometimes I tried that most faithful of the faithless translator’s tricks: equivalence rather than equation, what Erín Moure calls “faithfulness rather than fidelity.” For example for the delicate phrase “les pas de les absents,” I knew I couldn’t say “the absents” or “the absent ones,” so I dispensed with trying to match the precise delicacy she had achieved with the spareness of phrase and instead leaned back on what English does well, the monosyllabic: “the footsteps of those long since gone.” Devi approved.

Translating Devi transformed me. I know of no other way of saying it.