The same man who allowed Zora Neale Hurston to die in a welfare home after she spent her final years working as a maid for a white woman despite having devoted her life to diligently collecting all of the grunts and snorts, shrills and moans of his stupefied condition, in the fields, on the corner, at the counter, from the ceremony, to the hound den, the same man who found his own voice so pretentious he only whispered or screamed, couldn’t work the middle, has passed into the next part of his journey, died in his sleep while on a plane fleeing to Paris. Uncle Tom was born into slavery but earned his freedom dancing as a stripper for his white slave mistresses, they offered tips and pet his head until he felt as ready as a beast or an adulterer for his nightwalks. Freed, he moved to Eatonville and later to Chicago then Boston, where he made his living as a tailor by day though he never stopped selling to the white women, it was a bit more dangerous for a free man than it was for a slave, to be touched by the other race. Sometimes he missed the certainty of the whip, and he often beat his wife Julia with the good leather belt he had lifted from a deceased customer. That felt healthy and as close to love as he’d ever be, beating the black off the mother of his seven children. Uncle Tom had wanted to be a good man, the best kind of man, a faithful, deliberate, and always home on time kind, but he lost track of who and what to be faithful to and self disappeared in the losing of that. Mirrors were cruel and ever wide and descriptive of a bible and a broken field hand hiding in the scripted factory. Uncle Tom became a rapper after his first son ran away to live back in South where the cotton crumbled into women who could cook grits and shoot guns. He felt something stolen that only language could return or demand in currency. He felt like a stowaway in a bang up song and wanted to rewrite his hunted lingering. Uncle Tom became everything he thought about and he thought a lot about a house, about a stethoscope, about the road, about the joke in the song that became that hook that he then hung from, clapping. Uncle Tom was ridiculous, the greatest pretender. He couldn’t disagree with anyone, he never knew Duke Ellington from Monk from Andrew Hill from Cousin Mary, he didn’t want to recognize any difference between souls, and as bitter as this futile refusal made him, he smiled and tamed his will to recoil into a position on the lantern’s edge. Watchman. Sellout. He had so many disguises and all the cadillacs and pinstripes to match. A couple cardigans, hard dimples and soft socks, shamrock and ciroc. Free Meek Mill. Free the people, free the land. We mean it. And Mumia, and the mummies stolen from egypt and on display in some museum in England. Uncle Tom is a burning wish; he is a wish that burns eternal. He is a songbook purged through rehearsal, one who must be practiced to be destroyed, loved into uselessness, and then at last, gone.

Obituary for Uncle Tom

Feature Date

- November 11, 2020

Series

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

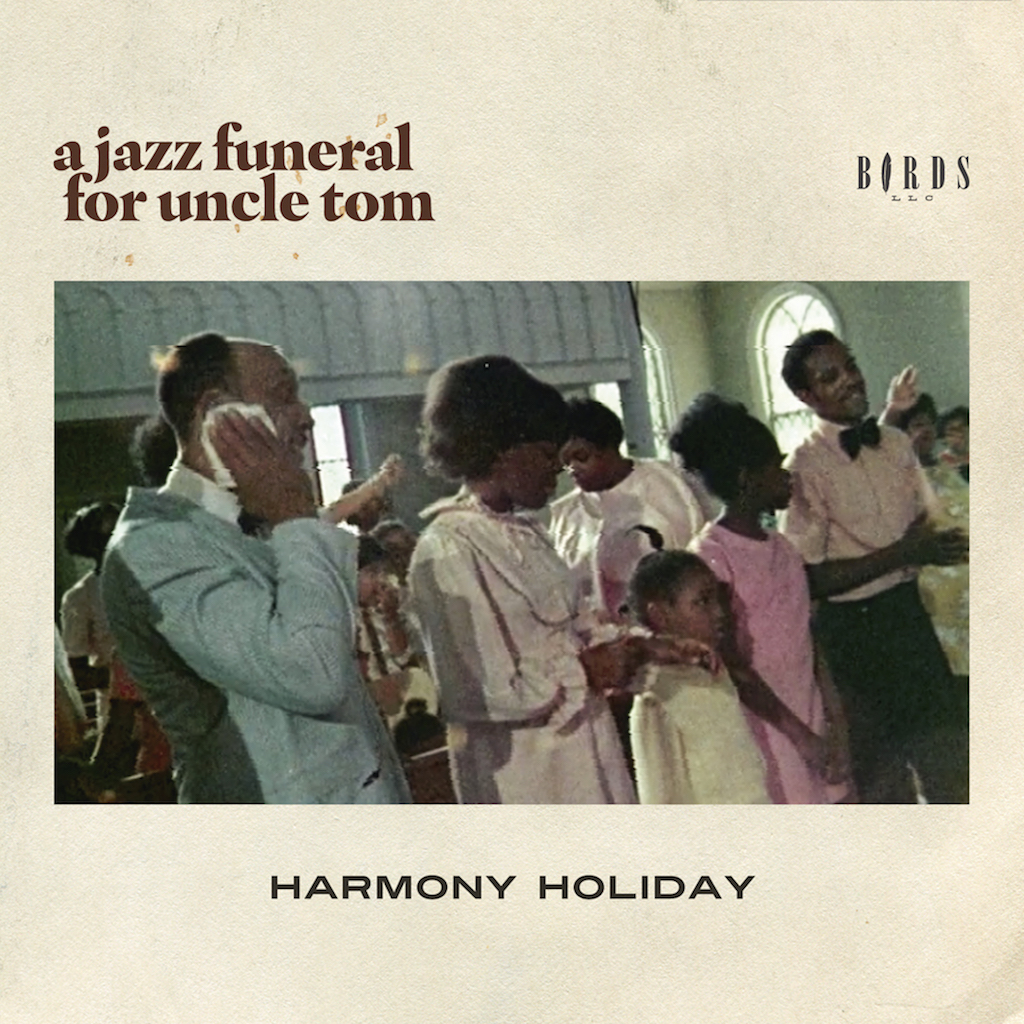

“Obituary for Uncle Tom” from A JAZZ FUNERAL FOR UNCLE TOM: by Harmony Holiday.

Published by Birds, LLC 2020.

Copyright © 2020 by Harmony Holiday.

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Harmony Holiday is a writer, dancer, archivist, director, and the author of four collections of poetry, Negro League Baseball, Go Find Your Father/ A Famous Blues, Hollywood Forever, and A Jazz Funeral for Uncle Tom. She founded and runs Afrosonics, an archive of jazz and everyday diaspora poetics and Mythscience a publishing imprint that reissues and reprints work from the archive. She worked on the SOS, the selected poems of Amiri Baraka, transcribing all of his poetry recorded with jazz that had yet to be released in print and exists primarily on out-of-print records and she is now editing a collection of his plays.

Harmony studied Rhetoric and at UC Berkeley and taught for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre. She received her MFA from Columbia University and has received the Motherwell Prize from FenceBooks, a Ruth Lilly Fellowship and a NYFA fellowship. She is currently completing a book of poems called M a à f a and an accompanying collection of essays and memoir, Love is War for Miles, both to be released this fall, as well as a biography of jazz singer Abbey Lincoln. Her work is deeply rooted by Black music, and collective improvisation with Black people, in the tradition of her father who was a Northern Soul singer and songwriter and introduced her to artists he worked with like Ray Charles, The Staples Singers, and Bobby Womack.

Winner of a 2020 California Book Award

"I’d recommend Harmony Holiday’s A Jazz Funeral For Uncle Tom, for how it blends lyric, imagery, and history to formulate a clear and striking narrative."

—Hanif Abdurraqib, author of A Fortune For Your Disaster

"In this extraordinary book-length sequence of linked prose pieces and lyric fragments, Holiday considers the role of visual rhetoric, particularly ads, in perpetuating race, class, and gender stereotypes. After presenting an image with two cropped and faceless subjects, the speaker remarks: 'We soon discover that the central question is who are we and what are we doing to ourselves? It takes years and years to turn the men real again.' Holiday invites questions of power and complicity in prose that is captivating and deceptive in its simplicity. She jostles hierarchies, mixing high and low culture, destabilizing a familiar language. The speaker seems to interrogate the intentions of the work itself, turning a rhetorical space into a stage for delightfully irreverent aesthetic gestures. In doing so, Holiday reminds us of the difference between performance and play. Through Holiday’s singular artistic vision, these remarkable poems reframe cultural exploitation and objectification, offering a stirring social commentary."

—Publishers’ Weekly, starred review

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.