The Art of the Rift: Translating Eva Kristina Olsson’s The Angelgreen Sacrament

1.

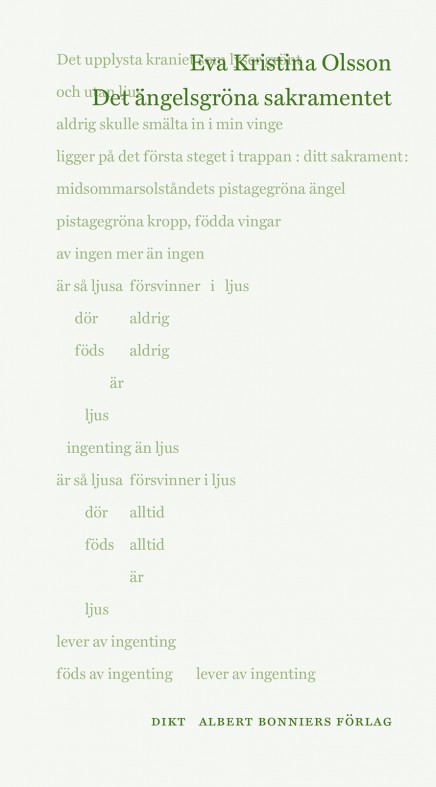

Right now (in fact right before I sat down to write this essay) I am working on a translation of Swedish poet Eva Kristina Olsson’s occult masterpiece, The Angelgreen Sacrament (Det ängelsgröna sakramentet), a long poem that both documents and re-stages Olsson’s encounters with angels.1 The poem focuses on certain ritual-seeming objects (staffs, shrouds, stairs), but the poem itself might be the ultimate ritual object, the object that folds in the other objects. To read the poem is to find out “about” these angels and Olsson’s angelic encounters, but it is also to participate in them, to be brought into an incredibly intensive experience.

When I asked Olsson in a recent interview about the origins of the book, Olsson told me:

But then she quickly pivoted to another source for the book:

As in the book—which ends with the line/dedication “to the angels and my first 12 years”—Olsson’s vision of the poem brings together something as different as angels and a dress she wore when she was a teenager: the extreme alterity of the angels coexists with the personal memory of a dress. Like the angels, the materiality of the dress—both its “green” color and the “pistachio” that gives a strange physicality to the dress—appears throughout the poem, at times it even seems to be a stand-in for the angels. But for me, it ultimately serves a role akin to that of the poem itself: the intensive materiality brings her (and the reader) into the dream, into the strange encounter.

In the intensity of this strange encounter, the difference between I and you, poet and angel, as

well as what is poem and what is object of poem collapses. In a recent essay I wrote for the Swedish poetry journal Lyrikvännen about McSweeney’s idea of “the necropastoral,” I argued that Olsson’s poem participates in what McSweeney in her book calls “strange meetings.” 3 As McSweeney puts it, these meetings “eat away at the model of literary lineage that depends on separation, hierarchy, before-and-after, on linearity itself.” Instead these meetings define the necropastoral with “its proliferation, its self-digestion, its eructations, its necroticness, its hunger, and its hole making.” As with Wilfred Owen’s poem, the intensity of the poem’s hallucinatory experience both dissolves and amalgamates self and other, this world and the dream.

2.

In my book Transgressive Circulation: Essays on Translation, I argue that translation challenges pervasive core US beliefs about the poem—or the lyric—especially the underlying belief that the poem is an expression of the subject’s interiority, and that this expression is threatened by noise that gets in the way of this act of idealized communication. With such a model of the lyric, poetry will always be what is “lost in translation”—or really “lost in transmission.” But I don’t think of Olsson’s book as fragile, vulnerable to my translation. Rather translation participates in the poem as “strange meeting,” “eating away” at hierarchies and divisions between I and you, reader and writer.

The other day I listened to the podcast Weird Studies, where one of the hosts, JF Martell, talked about the importance of “rift” in great works of art: “imperfections, surreal excesses, strange turns of phrase, inconsistencies…” 4 In difference to the traditional lyric model, where any “inconsistencies” make the artwork suspect, Martell argues that it is these very rifts that open the poem up, throw the reader into a “real” of artistic encounter. I would say that Olsson’s book is a “rifted” lyric. It’s a lyric but it goes on too long, it confuses who is reader and who is writer, who is angel and who is human. It even confuses the angel with a dress worn as a teenager.

Further, I think that translating the book has made me think about translation as an “art of rift,” or an art of exposing rifts in texts. For example, in Olsson’s book, one gorgeous feature is the repetition of the word “svepa.” This word can mean to wrap or to wind, as well as to sweep, but Olsson also uses the word “svepelse,” which means a shroud. Part of the beauty is to see the different ways the same word is used to mean different things, but this is something that I’m thinking about in the translation. Right now, I am introducing a number of different words—wind, unwind, winding sheet, sweep—to cover the different meanings, though I am not sure which of these I will ultimately use. There is a rift in the translation of the poem, an excess generated by Olsson’s volatile word usages.

Contrary to the impulse of saying that this means that the poem is “lost” in translation, I think this rift opens the poem up, sabotages the illusion of self-sufficiency, reveals it to be a deformation zone where variations and potentials are at play. This is very much in keeping with my vision of Olsson’s book: a process, an auto-digestion, a strange meeting: between reader and poem, poet and angel, translator and pistachio-green dress.

As a translator (or publisher of works in translation) it is generally my hope that the foreign text—auto-digesting and volatile—will enter into the US literary system, rifting open the conventional frameworks: Is Olsson writing confessional poetry or spiritualism? Religious kitsch or lyricism? Lyric or long poem? My hope is this will lead us to further strange encounters, not just with Olsson’s own poem, but, when the rift of the foreign has thrown us out of the comfort of US literary convention, a re-encounter with US poetry itself.

__________________________

1 The Swedish original was published by Albert Bonnier in 2017. My translation will be published by Black Square Editions in Spring of 2021.

2 The complete interview can be found here.

3 The Necropastoral: Poetry, Media, Occults by Joyelle McSweeney (U of Michigan Press 2015)

4 “Love, Death and the Dream Life.” Weird Studies 79: https://www.weirdstudies.com/79