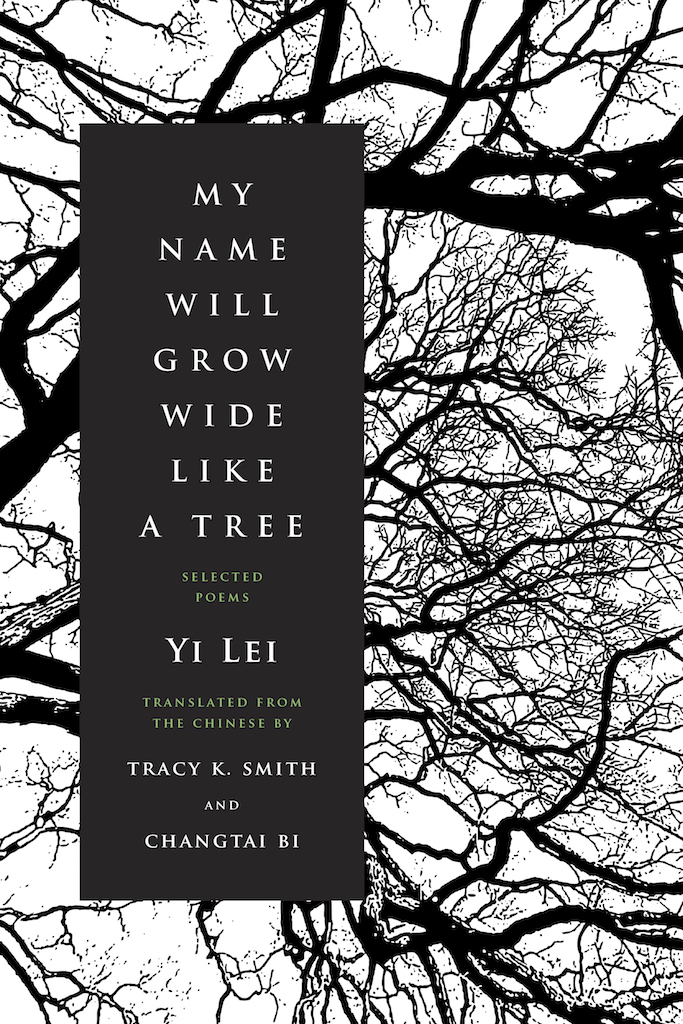

All Are Welcome: Translation as Permission

In 2013, a friend of a friend suggested I make time to meet Chinese poet Yi Lei while she was visiting New York. I was given a literal translation of her most famous poem, “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” by way of introduction. Reading that text was like catching sight of someone through a foggy window: details and key features must surely have eluded me, but some deep and abiding sense of character shone powerfully through. I needed to know more about this poet. I needed to dwell upon the things her spirit and voice had caused me to feel, see, long for and believe.

I don’t read or speak Chinese. Over the years of our relationship, every bit of communication I had with Yi Lei was the result of an act of mediation. And yet barriers like age, nationality, language, culture and race, which ought to have made us less recognizable to one another, instead became vantage points inviting us to see one another and ourselves anew.

The poem that comes to mind most readily when I ponder the intimacy and identification I came to feel with Yi Lei is “Black Hair.” In it, the speaker contemplates feminine power, beauty, freedom and vulnerability. While relatively brief, the poem strides through contexts and across scales until it begins to feel epic in its intention. Working on the poem, I saw clearly how the recurring image of black hair signifies within the specific context of Asian femininity, and yet in my hands—in my mouth—the phrase “black hair” began to make space for a second set of values and vulnerabilities as informed by my racially specific experience.

This poem gave me a new vocabulary for understanding the effect my presence in Yi Lei’s poems might seem to constitute. Beyond the conduit or medium I had long sought to be, I realized that I was also an audible presence there beside the poem’s original speaker, harmonizing. I knew full well that this two-voiced translation might be problematic for a reader who seeks to be left alone with Yi Lei and her poems. But what might it mean for another type of reader, the reader who finds, to her surprise, space for two or three or many distinct voices to cohabitate in these lines?

This is the miracle of translation, to me. I am elated that a Black woman in the US, alive in the midst of a national racial reckoning, might find her reality bolstered and clarified by a Chinese woman’s poem written on the eve of political uprising. What might it mean for a reader to be assured that her self as marked by race or any other signifier of identity need not submit to being an effaced presence in another poet’s lines, need not be a silent witness or mute interloper? What might it mean for a reader to be urged into vocal participation? What might it mean to be told all are welcome here?

And if all are, indeed, welcome here, what might the future of translation look like? What will we learn about ourselves and our neighbors across space and time when we admit that I am a viable conduit for you, no matter who I am, no matter who you believe yourself to be? What will we become when we begin to hear the music our voices and our lives make together?