In 1997, I was sitting in the office of my MFA program advisor, a fiction writer. I don’t recall exactly what we were discussing—a story I’d written, a story we’d read in class, likely both. Neither do I recall what prompted my advisor to say, “You know: you may actually be a poet.”

This was the second year of the two-year program, and I remember feeling freaked out, energized, and deflated by the comment all at once. I’d come to the program with little confidence in my talent and even less about my identity as a writer. It had taken me all of the first year just to try The Artist’s shoes on for size, faking it until eventually, maybe, making it. It did me all the good in the world to receive serious feedback from serious people, and to read and discuss serious literature. My fear that you either ARE or AREN’T a writer—from birth, or based on your college major, or the people you hang out with, or whether your parents talk about Cheever at the dinner table—was just starting to dissipate as I focused on the words I generated (and revised) on the page, and the ones I read that were transforming me deep in my bones.

But now: you may actually be a poet? What the hell did that mean? My advisor meant it seriously but not-too-seriously. Still, alarmingly, it resonated with me. On some level I knew what it meant. I’d been finding narrative short story-writing forced and clunky. I loved words, sentences, punctuation, the sounds & rhythms that words made when you arranged and rearranged them, the ways those sounds & rhythms made you feel or see something differently, more intensely. I wrote with my ear more than my mind. Later that semester I submitted to workshop a story that was really a collection of scene fragments, collaged together, revised on the line level ad nauseam but hardly narrative—yet for me very much a coherent emotional-spiritual whole. It seemed unlikely that anyone else would feel the same. But it turned out most of the class, and my advisor, did feel that coherence. It went over well, meaning something had broken through; I had found a way to translate my untranslatables, express my ineffables. Through crafted fragmentation and refraction, art and meaning were happening, or beginning to happen; and I wasn’t faking it anymore.

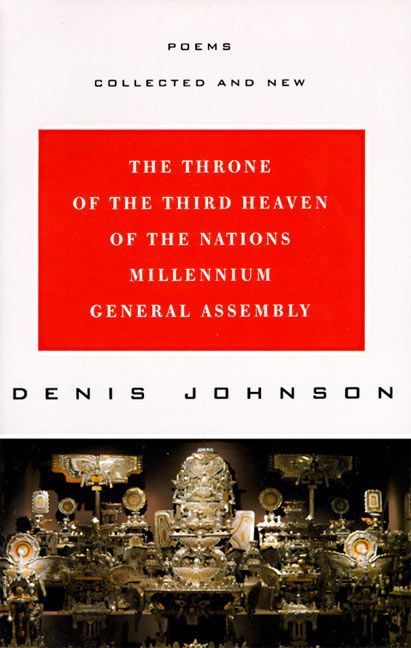

My advisor furnished me with a list of linked story collections—perhaps a prose form I should try—including Denis Johnson’s Jesus’ Son. People were buzzing about it, floored by the way brutality and tenderness, despair and beauty, danced together so compellingly. You could see this in story and character, sure, but mostly I was taken with how Johnson did this in language: it was clear to me that he was “actually a poet,” an ear writer, a word and fragment arranger; and indeed it turned out he was.

The Incognito Lounge was Johnson’s third collection of poetry (he published four before turning primarily to prose). The title poem killed me the first time I read it. Rereading it—both on the page and listening to a recording of Johnson reading it aloud—has been like bathing in enchanted waters: deep pleasure, stimulation of youthful muscle memory, refreshment. Johnson marries the gritty American mundane with the gorgeous sublime like no other writer. His desolate motel-like courtyard setting in Phoenix—“Alleys of dark trash, exhaustion”—is “the center of the world,” one of countless “towns of earth” where the faces of his neighbors strain to be human – “like a baseball with glasses,” “an empty, empty face,” “no face at all,” a face in which “nothing is possible,” faces that “go blank.” Yet these same figures pulse and glow in the strange light of loneliness: “looking like he’s made/out of phosphorous,” in a world “full of megawatts,” a “pale, electric light”; that meaningless, familiar, somehow also seraphic “standing in a dark house at midnight / before the open refrigerator, completely transformed in the light…” Think Edward Hopper, his lonely figures plucked out of their rarefied social class and passivity, dropped into the arid Southwest and infused with raw yearning … for answers to “questions of happiness,” to be touched by the “lady with no face,” to “Maybe permit yourself to find/ it beautiful…”

The thing about Johnson’s work is that it’s tempting to think it’s about being “married to a deep comprehension and terror”; but it’s also I think always about “how inextinguishable it all is”—light, loneliness, the heavens, the pursuit of happiness.

I chickened out, by the way, on pursuing the question of whether or not I was a poet—to this day wondering if I should start over, take some classes, give it a shot. I’m pretty sure it doesn’t matter. Though, I rather like this potential prescription for my writing life henceforth: “And so on—nap, soup, window … smaller and smaller words.”