Or How to Do Things With Words, When You Can’t Leave the House

I’ve been reading a lot over the last year, but much of it has been long, old novels. I’m always drawn to the allure of imaginative transport and brushes with the sublime afforded by narrative, and this year the draw has been especially strong. Being a poet, so much of my own mental life tends towards the fragmentary, momentary, and emergent, and that can be a wonderful habit of being, but it can also be emotionally exhausting. This tendency leads to ecstatic moments. Often, in an inhospitable world, ecstasies of worry. So, the durational extension of Proust, Dostoevsky, and Dickens has been a relief to me in my hermitage.

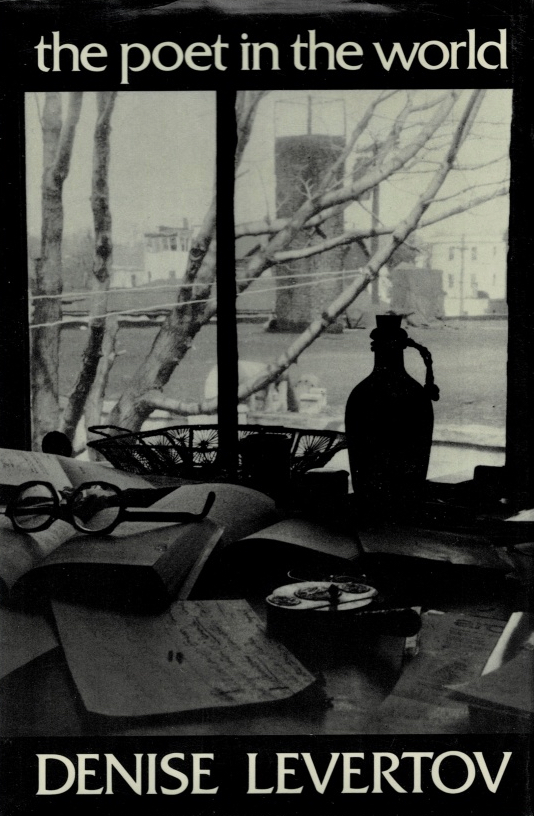

But I have been reading poetry, too, of course, and essays on poetry. One of the books that has meant the most to me over the last year has been Denise Levertov’s The Poet in the World. I guess there is some irony in that, since I have been less in the world this year than ever. That’s true anyway if what we mean by “the world” is the space of flesh-and-blood social congress. But, if I’m honest, I feel like I’ve been less and less in that world every year for some time. I hardly need to say the internet is partly to blame. But the internet is only a tool, and much of this retreating is a consequence of my own temperament and the process of getting older.

Levertov’s sense of “the world” is, naturally, quite sophisticated and can’t really be reduced to anything as simple as “what’s going on out where the action is.” At a fundamental level, the world in her title refers to an Heideggerian entanglement of existential elements: the webs of interrelation between subject, object, and consciousness (as opposed to more traditional divisions between those entities) that Heidegger’s term “In-der-Welt-sein” (being-in-the-world) suggests represents the human situation.

Seeing the world in this way is not quietism, and Levertov was never shy about the relationship, for example, between poetry and politics, crisis, and social change. We are, as she says, “living our whole lives in a state of emergency” and therefore have no choice but to resist the petty politics of disenfranchisement peddled by nationalist revanchism and instead to embrace a truly radical form of conservatism—the effort to “save that earthly life, that miracle of being, which poetry conserves and celebrates.”

Levertov’s argument is also a disclosure of the writer’s ethical obligation to regard words as a form of action with the same ethical implications of any other form, viz.:

The obligation of the writer is: to take personal and active responsibility for his words, whatever they are, and to acknowledge their potential influence on the lives of others…. When words penetrate deep into us they change the chemistry of the soul, of the imagination. We have no right to do that to people if we don’t share the consequences.

I’m inclined to make a leap here that Levertov only implies and say the writer’s obligation is to try to love the world in its terrifying emergence and even in its hatefulness, as a neighbor and sometimes an enemy. For me, at least, this has been a healthy corrective in my darker moments in this challenging time, staring at a screen instead of a world of faces.