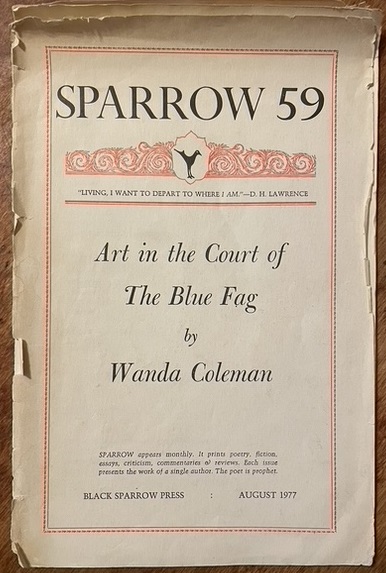

I don’t remember by what means I first became aware of the sui generis WOW of Wanda Coleman, but I do remember that the first book of poetry I ever bought, for myself, outside of required texts for classes, was one of hers: a thin, paper/staple chapbook from a magazine rack at Beyond Baroque, L.A.’s iconic poetry clubhouse in Venice Beach. Art in the Court of the Blue Fag by Wanda Coleman, Black Sparrow Press.

It was such a strange title, heralding some kind of Elizabethan-meets-punk/drag-Los-Angeleno scene, and “fag” disquieted me: were people allowed to say that, write that, out loud? It seemed a little subversive to me then, at nineteen, fresh off the highway from Lancaster, an hour northeast in the Mojave Desert, land of alfalfa farmers and aerospace engineers.

It was 1984. I was starting my first year at Pitzer College. My favorite poet was Sylvia Plath.

Easy to pooh pooh that, huh, such a cliché! But listen: it was the incredible force of voice in Plath’s poems that captivated me: her singular female voice, and an uncanny gift for making vivid images. Plath was the whole opera: set and aria. I think reading Plath had prepared my enthusiasm for Coleman’s work. Later, of course, time and education would teach me that the stages they sang from were very different. Yet in their vocal and linguistic intensities, in the incisive and sometimes brutal way they analyzed and expressed the world, they were kin.

Standing at the magazine rack at Beyond Baroque, I opened Coleman’s chapbook at random and read: “She kept it in a black green felt-lined box.” Ten monosyllabs—how I loved saying them, each one a kind of floating stone in the mouth—introducing the speaker’s “thang”: seductive and dangerous, wreaking havoc on her love life. It seemed so clear, didn’t it, that this “thang” was a snake, something that could really open its jaws.

And the snake represented the speaker’s sexuality, didn’t it, my AP English brain surmised, my hormone-driven nineteen-year-old body confirmed: look how she’d “take it from its box/caress it gently, lay it on the bed/watch it glide easily over the blanket…”

And yet there was something about my interpretation that felt incomplete. For years, I just couldn’t get at it: snake, sexuality, ____?

And then, over ten years later, preparing to teach a bunch of Coleman’s poems, it hit me: of course! That “certain rhythmic motion;” how “after having invested so much time in the thang/she couldn’t bear to throw it away”—her thang was her poetry! Beloved, seductive and dangerous, intimidating the men she got involved with, snapping one of them up with a gulp, so that “it took a long time for that lump to go away”—so comic and so pointed. This was a poem about sexual politics of a particular order and one with which I could, by my early thirties, completely relate. Suddenly the last two lines ramified: “a friend suggested she sell it/she’s into that process now.” Maybe this wasn’t a tale about giving away one’s power in order to stay relationally “fit”—maybe this was a tale about deciding to publish, frightened men be damned.