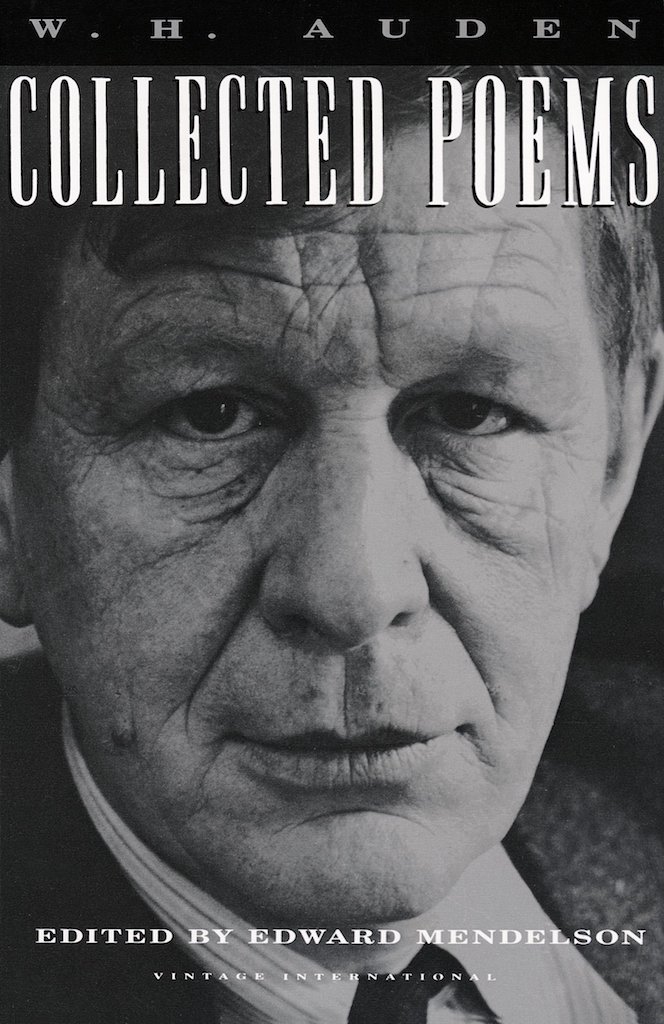

I found “Petition” by W.H. Auden in a thrift shop paperback anthology from the fifties.

I loved the way the second line complicated the first line, though I did not completely get the entire shebang as a continuous statement. “Sir, no man’s enemy, forgiving all/ But will his negative inversion, be prodigal.” But I trusted obscurity, the switcheroo in point-of-view from talking-to-you, Sir, to talking about you later in the sentence in the third person. Athlete. The English comma seemed more about attitude than grammar. Will you wear that shirt, Lord? Will you be prodigal, though inverted? And what on earth was a “negative inversion”? Isn’t that maybe good? No living teenager wants to have “ingrown virginity.” Painful toenails. The Smiths.

Naturally, I enjoyed the subtle rhymes so much that I did not even notice them, nor the poem’s sonnet form, a perfect spell working on my barely conscious mind because here, in the last line and a half of the poem, was a sentiment so sudden that I could, without embarrassment, sport around with it typed and taped to my binder on a strip of paper, a fortune cookie fortune, a restaurant’s first dollar: “look shining at/ New styles of architecture, a change of heart.”

The sound of distant eloquence is its own charm. Today my favorite line is “Prohibit sharply the rehearsed response.” Those days in Pittsburgh, I could walk a mile or two to see a big sooty dark neo-gothic skyscraper on the Pitt campus, nicknamed the Tower of Ignorance. Or I could take the bus downtown and see the giant castle made of mirrors, the brand-new, postmodern PPG Place, a building that mirrors and distorts the local landmark that inspired it, always looking to shine, even in the rain.