One of the joys of Autumn has been wandering the nearly 700 pages of Jane Augustine’s Traverse: Collected Poems 1969 to 2019. Paradoxically filled with Augustine’s light touch, brief lines, and white-space silences, the volume manages to be both monumental and warmly open, crossing what Andrew Schelling has called the “wry vernacular” of Objectivism with a woman’s intimate eye.

Spare, unselfconscious, nearly transparent, Augustine’s poems reach out to the things of this world like a ship whose constant soundings describe its own location. No part of her lived experience is excluded, so a reader may find herself meditating on a painting, carrying a backpack, searching for a homeless man under a scaffold, or pulled suddenly back to a parent’s death-night twenty years before. Witnessing may be delicate—as when rain during drought:

freshens grass-tips, not

deeper

“Rain”

or brutally physical and female, as when

gloved hands

lift out the baby

blood mucus pain

alive—

the mother laid

open helpless—

my body mine—

alive

on the street

in hard light

“Incident”

The southern Colorado Rockies are a touchstone—her beloved Sangre de Cristo range, where the self is drawn out into Earth’s unending thingness, till stillness and motion become interchangeable, a syntax waterfalling down uneven levels of line toward insightful pause.

No pressure to move the mind

which doesn’t slow any more than

the exuberant diamond chilling

stream rests. It sends

its overflow into calm shallows.

“At the Aspen Stump Again”

At once completely matter and completely spirit, the range and its waters form a living, touchable presence through births and wars, travel and aging, a son’s drug addiction, a daughter-in-law’s slow death from cancer.

Red-brown fluid dribbles from the

corner of her mouth into the kidney-shaped basin.

I empty it repeatedly

into the mauve plastic bowl

beside me on the floor

until I can’t stand to look

down into that little lake

of darkness deep as the world.

“A Tomb for Michelle”

Whether here at death’s bedside, walking in Paris, or waking under mountain-clear stars, Augustine’s words tend to touch and move on, enacting her Buddhist perception that motion and intersection give rise to all things, including both insight and art—that “skewed composure / of what isn’t yet mastered” (“In Provence, Near Venasque: Le Beaucet”). Through multiple landscapes and changing moods, this openness of form allows attention to alight where it will, at times with a Marianne Moore-like pinch of wit, as in this invitation to put on:

a shirt bright as bougainvillea

and white summer sandals

to walk the city

whose sewers one may

visit

“In Paris Again”

or this moment on a plane about to take off, when a sense of enclosure and the upcoming birth of a grandchild fuse:

the way the blood-rush circles

through the amnion, nourishes

the baby to come—the souffle

of waves, of airconditioning—

audible through the stethoscope

held to the pregnant woman’s belly

“Takeoff, Taking In”

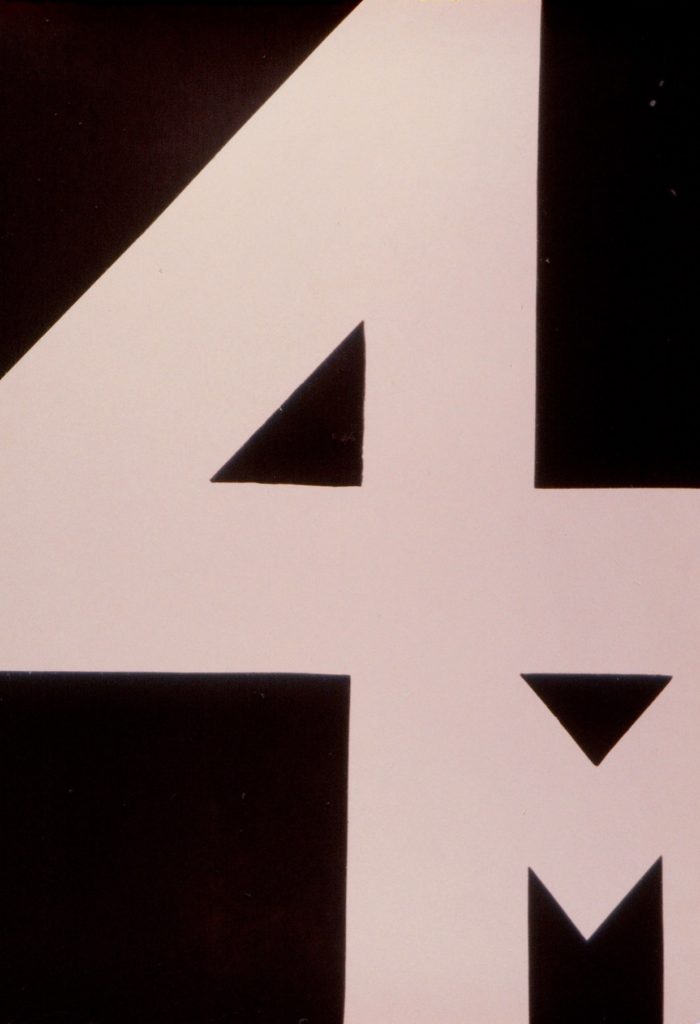

For readers new to Augustine, the biggest surprise will be flipping a page to arrive at the opening of Krazy: Visual Poems & Performance Scripts, a 2015 volume that rescued from the age of slide projectors, tape recorders, and typewriters an ephemeral chapter of 20th century feminist poetics. Unpublishable until the age of scanners, these Concrete poems and vocal scripts are difficult to excerpt, requiring a reader’s interaction to conjure the playful borderlands of eye, ear, and performance. As in the original edition, each visual poem is paired with the text or script that follows on the reverse page, a sequence that requires our attention to rest in the visual before escaping to more familiar and voiceable forms.

This visual interlude reminds me to mention Traverse’s many ekphrastic poems, whether formal meditations like “Draughtsmanship, or What Is Not in the Portrait”, in which “Albrecht Dürer with one hand drew the other finely,” or random encounters with shop-worn icons of culture, as when:

Our Lady in dulled aura

of uncleaned gold opens

accepting hands over the

holy book and microphone.

“Notre Dame de Blanc-Manteaux”

More intimately related to Krazy are poems that reflect on or imagine performances, such as “Live Painting,” in which the moment of creation—performed live on “thick paper… / cut from a human-body-size / sheet” trembles with beauty, playfulness, and terror.

So we went on

the painter first

fearless of course

bold black, porcelain turquoise,

that Chinese stroke

and the poet

in terror

to make a mark.

“Live Painting”

Since wandering a text grants permission to turn in most any direction, I’ll bring us back to what I think of as classic Jane Augustine—a mountain, a tree, the play of black ink against white page, and the quietest, world-touching light of her attention:

Consciousness

doesn’t make much

of itself, touches

lightly, breaks off,

resumes.

Evergreens spread

dry needles, a sign

that they live

for a while.

“Once More at Rosita Cemetery”