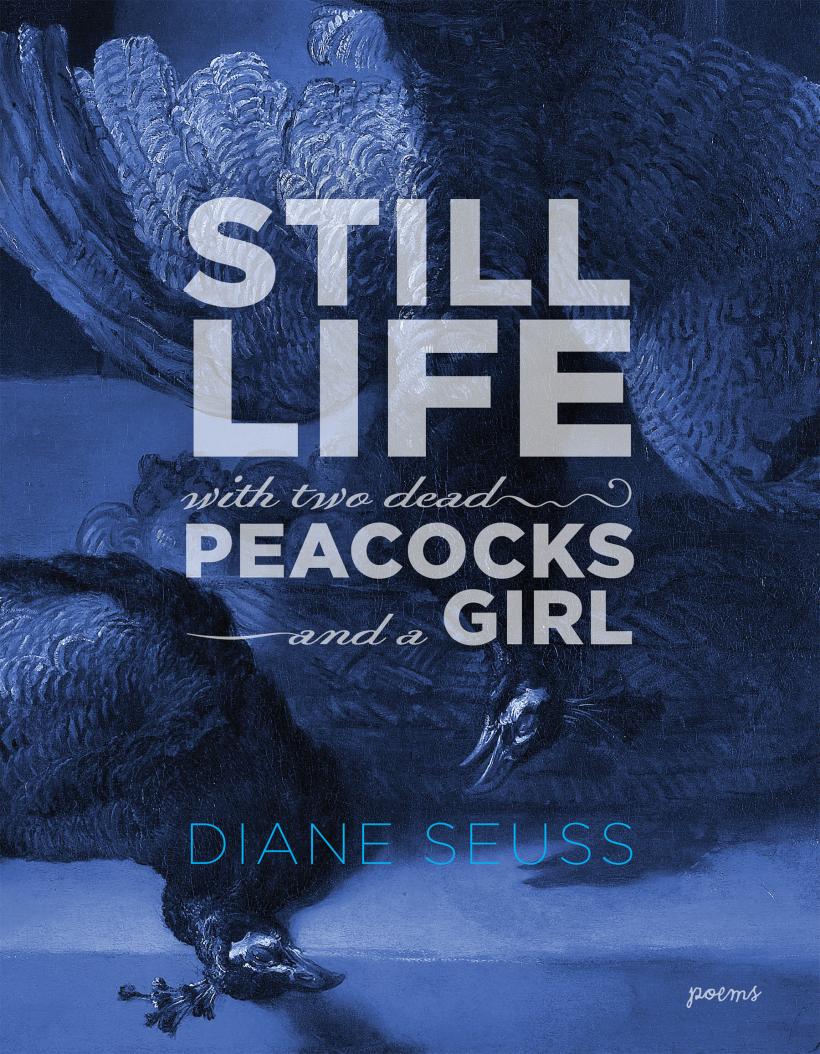

When I try to think of a poem that sparks poetry for me, I come back to “Still Life with Turkey” by Diane Seuss. The poem starts off with a crisp description of a dead turkey as if describing a Chagall or Van Gogh. Seuss writes, “My eyes / are in love with it as they are in love with all / dead things that cannot escape being looked at.” Seuss goes on to describe a father in a casket and a young child who is asked whether the child wants to see the father in the casket. The child says “no” after overhearing others describe the father’s body as not looking like himself. Seuss writes, “Now I can’t get enough of seeing, as if I’m paying / a sort of penance for not seeing then.” The speaker goes back to the description of the turkey and finds such beauty in the dead bird: “and the glorious wings, archangelic, spread / as if it could take flight, but down, / downward, into the earth.” Even if diving downward into the earth, this dead bird takes flight – it is reanimated, reincarnated by Seuss’ words. This ekphrastic interpretation of a dead turkey sparks in me a need to further explore my obsession with death and with the delicate, disastrous beauty of it.

I’d say my exploration of death started in Diane Seuss’ classroom. I will always remember her asking the class to think about the image of a beached whale and to ask ourselves what was our beached whale? Honestly, I’ve got several beached whales, who doesn’t? But my primary would definitely have to be death and the uncertainty surrounding it. I was raised Roman Catholic with the idea of resurrection and heaven or hell always looming on the other side. But I also learned about the Ancient Egyptian beliefs of reincarnation. My Aunt Jenny, my mom’s sister, died of a very quickly consuming cancer when I was in second grade, and I remember feeling so comforted by the notion of reincarnation. I was not yet old enough to fully grasp the loss I’d experienced or the sadness my mother carried, but I was certain that death is not a sudden end so much as it is also a beginning.

When my sister, Rachal, died suddenly at 28 years young, I met up with Diane Seuss at a café, and she read my tarot cards. I felt a need to return to her, not only as my poetry mentor, but as someone who has also studied death, who has experienced that loss and both looked away and refused to look away. When my sister died, I refused to enter the surgical room when they removed her breathing apparatus. My father, my sister’s boyfriend, and my mom’s then partner all watched as she took her last breath, but I could not. And then she was cremated so there was no more looking at what was her beautiful head of permed black hair. I think part of my draw to “Still Life with Turkey” is the refusal to see the father in his casket, the processing of that decision, the decision to not look at death. In my writing, I look at death all the time. But when it came time to watch my sister die, that was impossible. But I knew when it happened all the same. I felt her spirit pass through my body from the top of my head through to my toes, and I turned around, and the nurse came out of the surgical room and said she passed. And so, despite my not looking, my sister came to see me and say goodbye in her own way.

A year and a half ago my father passed away, and I was determined to be there. I was determined to watch him die. To hold his hand through his last breath. In the months leading up to his death as he developed dementia, I could tell that he was halfway here and halfway gone. He would talk about seeing his mother who had died 25 years ago, his sister, who had died 15 years ago, his daughter, my sister, who had died eight years prior – they all visited him in his dying days. On my birthday he asked me to tell him about death. To explain what would happen to him. I explained that he would be loved in this world and in the next. And that is all he needed to hear. Ten days later, he died, but I was not around to see it. I’d just left for the night after sitting with him for three straight days listening to his death rattle. He passed once I walked away.

All of these cumulative experiences of death and all the ones yet to come and all the deaths that aren’t even in my view, they are my beached whale. They are beautiful yet difficult to see up close. The only way I’ve ever been able to explore is from a safe distance. However, the exploration of death in all of Diane Seuss’ poetry collections inspires me to zoom in a little closer, to love “its saggy neck folds, the rippling, variegated / feathers, the crook of its unbound foot.”