And I should raise in the east

A glass of water

Where any-angled light

Would congregate endlessly.

—”Water” by Philip Larkin

Soon after I left secondary school in Saint Lucia in 1967, I was introduced to the arts and theatre circles around Derek and Roderick Walcott by Mac Donald Dixon, poet, playwright, actor, director. Through Patricia Ismond, then a recent graduate of the University of the West Indies (who later became a respected Walcott scholar), I became aware of Caribbean and other modern literature. I studied 20th century British poetry and fiction with Patricia Charles, a white American who had married into a Saint Lucian family and was to spend the rest of her life making a great contribution to our social life, through the arts and other areas. I mention these mentors and their influence since those years also marked the beginnings of my creative life in literature and theatre.

In our public library I found many anthologies of literature, and read voraciously all kinds of poetry, novels and plays. I still remember the war poets Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke. Then and later, as I moved to the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill, Barbados and general studies in English and French Literature, I discovered and came to admire Eliot, Yeats, Auden, Dylan Thomas, G M Hopkins, Thomas Hardy, D H Lawrence, among many others. I also reveled in Shakespeare, Donne, Wordsworth and the Romantics.

But it was the Moderns who caught my imagination and who I imitated in my early efforts at writing verse. My studies brought me closer to the great Caribbean writers like Walcott, Kamau Brathwaite, Martin Carter, Garth St. Omer, George Lamming, Jean Rhys, V. S. Naipaul and others. Walcott and Brathwaite would remain major influences well into the more mature years. American poets like Allen Ginsberg, Robert Lowell, C.K. Williams, Elizabeth Bishop and others would become important guides later.

I probably discovered Philip Larkin at university. I do not think he was on our syllabi. Did I find him in anthologies? I also recall listening to him read on long-playing vinyl records which I borrowed from the library. However I discovered his work, I still remember clearly my enthusiasm for him and how he became a model.

What did I like about him? In writing this, I read again his slim volumes, The Less Deceived (1955), The Whitsun Weddings (1964), High Windows (1974) and the later Collected Poems (1989) edited by Anthony Thwaite. And I was struck by the unforgotten familiarity of so many lines lying in the subconscious memory, now easily returning. I liked all over again the power of his descriptive-narrative poetics, very close observation of the ordinary, of human nature, emotions, cities, rural settings, the way he added incrementally as he passed through to his conclusions. Conclusions that were in the main skeptical, reflection of the popular doubts of modernity, an understated tone of a certain agnosticism. And everywhere, through all the collections, poems haunted by the finality of death.

And while, in my early self-conscious twenties, the world-weary tone had a certain appeal, I was more interested in poetic structure and the shaping of poems. I wanted to imitate and so learn how it was done, the crafting of verse, whatever the theme. So Larkin’s structured neo-formalism (in reaction to the radical modernism of the twenties), his half/slant rhymes within complex rhyme and metric schemes, appealed greatly to me.

Much of my verse, even now and after those early years, still prefers half rhymes to hard rhymes. My poems are carefully structured, carrying a certain formalism (if one looks closely), creating music rooted in the traditional devices of rhyme and alliteration which support my strong Walcott-influenced use of metaphor. These I learned from Larkin who remains an enduring, foundational influence.

I suppose in retrospect, fifty years later, no longer sitting as an apprentice at the master’s feet, Larkin’s poems can seem self-limiting, in themes and forms, working within a narrow circumference, even as one recognizes a concentrated brilliance. He remains the poet of a sad, keenly observed nostalgia of the past, filled with self-ironic regret for what never happened in a time “that no one now can share.”

“Church Going” is certainly one of Larkin’s and the twentieth century’s classic poems. All his usual themes and tones are there. As is his recognizable traditional form. He builds on 7 nine-line stanzas, pentameter, half-rhymes, his usual safe structure. The music is the low organ tone of a conversational voice describing with accuracy and closely observed detail what he is seeing. A certain, shy hesitancy echoes in the first two stanzas. He enters, “once I am sure there’s nothing going on.” His genuflection is made in taking off cycle clips “in awkward reverence.” Respectful of the imagined holiness of the place, he reads from the lectern and pronounces “‘Here endeth’ much more loudly than I’d meant.” His doubt hears “the echoes snigger briefly.”

If the first two stanzas show the descriptive-narrative gift of Larkin, the following five bring his analytical mind to bear on what he has experienced. The empty church reignites his familiar theme of loss of religious faith, possibility of the disintegration of Christianity into a return to pre-Christian superstition — “will dubious women come / To make their children touch a particular stone;..?” — the churches falling “completely out of use.” Will the great cathedrals become museum pieces of interest only to builders who “tap and jot and know what rood-lofts were? / Some ruin bibber, randy for antique…”; or will they and what they once meant, be of interest only to persons like him, “surprising / a hunger in himself to be more serious, / And gravitating with it to this ground, / Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in.” But in typical Larkin mode, while the church remains “A serious house on serious earth it is, / In whose blent air all our compulsions meet” it is also an “accoutred frowsty barn.” And if it is a source of wisdom, it is because “so many dead lie round.” Death is the ghost that haunted him.

Larkin and many of his literary contemporaries of the post world-war years, following the disappointments and loss of faith of the writers of the twenties and thirties, reflected their own agnosticisms in a plain verse, a new formalism that was vehicle for their own loss of belief in religion and political ideologies. “Church Going” (and the bulk of Larkin’s work) certainly spoke for and to their generation with influence and a certain irrefutable logic.

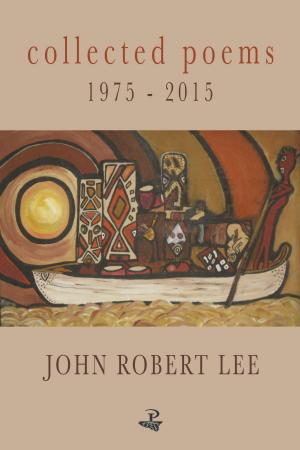

If I did not take from Larkin his skepticism and lack of faith, I took, and still take, however subsumed, his neo-formal poetic forms, unfussy, concentrated, a modest musical tone playing on half rhymes and perhaps above all, the finely detailed and close, film-like observation of the world around him, physical, natural, and emotional. “Church Going” was one of the poems I copied as I learned from him how to shape such pointed, accurate stanzas. One of my most anthologized poems, published in my Collected Poems 1975-2015 (Peepal Tree, 2017), “Skeete’s Bay, Barbados”, modeled itself on this poem in form and tone.