When asked the perennial question of what book he would take to a deserted island (or the Argentinian equivalent in the ’50s), Jorge Luis Borges said he would take a dictionary.

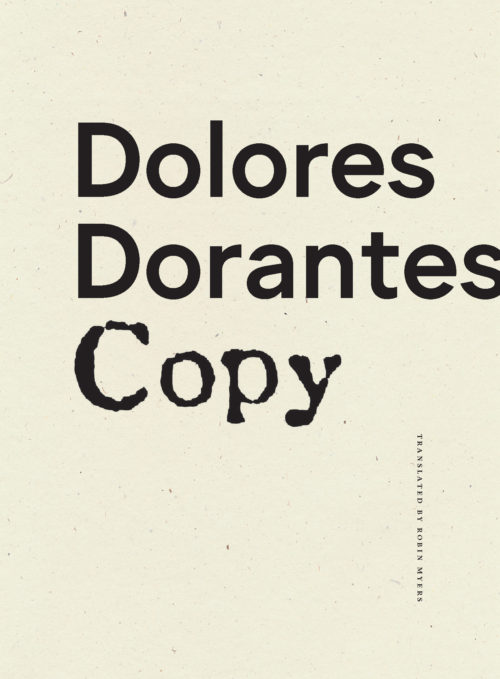

He did not hesitate. Or, at least, I didn’t imagine he did when the story was told to me in the dark classrooms of my crowded university, in my crowded city, during my crowded youth. If the question were asked to Dolores Dorantes, I’m positive she might give the very same answer. The joy and strangeness, the solace and disquiet written into the very structure of the dictionary, shapes this strange and lucid book, carried into the English by the always bright Robin Myers. The series of dictionary entries which appear throughout its pages constitute the prime matter from which Dorantes produces her own work: poems of unsettling and sharp intelligence, which include fragments of certain definitions to underscore the incongruity at the very heart of defining. How is it possible, the poet seems to ask, for one word to be defined in terms of another? How, again, for a single thing to be called by different sounds in different languages? The very premise of defining also constitutes the first manifestation of the copy in the latest book by Dorantes.

These fragmented definitions, along with other phrases, iterate over and over in her poems. Are, indeed, copied. In its use of permutation, these poems seem to be written in the tradition of the pantoum or the villanelle. The obsessive repetition distinctive to those forms haunts Dorantes’ work, but also the same mysterious and almost imperceptible progress, the piecemeal transformation of meaning.

Dolores Dorantes is a Mexican poet who was forced to flee her country due to violence and seek refuge in the United States. Taking the cue from the book’s epigraph, I choose to read its poems as meditations on exile and migration. Expressing emotion, says Mahmoud Darwish at the opening of the collection, (…) is not one of the attributes of exile. And, indeed, these poems seem to veer away from language traditionally aligned with emotion and, instead, to commit to a tone stripped of feeling, abraded by repetition. Her word-choice and the tone of her poems, along with the use of iteration, seem to reflect on how language is wounded by experiences that break into the very framework of identity. Her poems beg a series of potent and actual questions: What do we have left after such violence? What happens to identity when the structure that bolsters it, giving it permission to exist, collapses? What is lost but, also, what is gained in this displacement?