Get to Know Your Neighbors

The skin my fingers lightly brush is brown, is rough, is wet; I’m touching a lake sturgeon. I’m leaning against the edge of a touch pool at the Great Lakes Aquarium in Duluth, Minnesota with my hand immersed in water well above my wrist. This was in the late aughts when I lived in Bemidji, a small town in north central Minnesota, and my parents were visiting from Georgia, and we’d decided as close as they were, they should see Lake Superior, the world’s largest freshwater lake when measuring by surface area, what can be seen, and not volume. And since we were at the lakeshore next to an aquarium, it seemed we should go to the aquarium. Some of the first animals that fascinated me were fish. Fish tanks were a fixture of my childhood, thanks to my dad. And he and I had never been to an aquarium together.

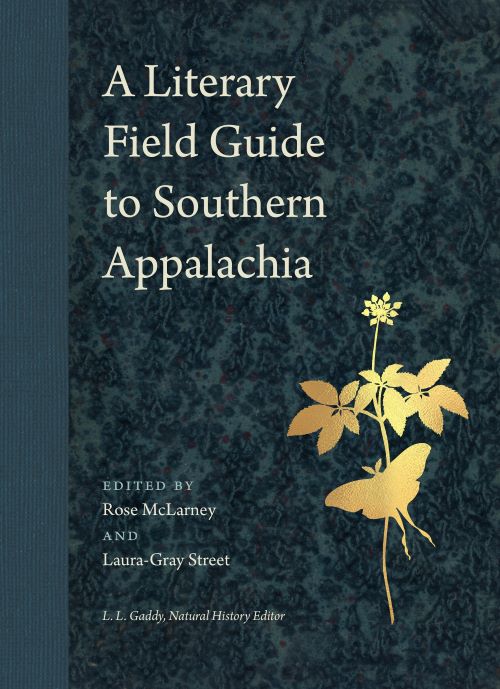

In 2017, around ten years later, I was invited to write a poem for the anthology A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia edited by Rose McLarney and Laura-Gray Street. In the years since that visit to the aquarium, I’d moved from Minnesota to Alaska and only recently to Statesboro, Georgia, a couple hours southeast of where I was born and raised. Though I grew up where the Fall Line meets the Piedmont, I’d also spent a fair bit of time in southern Appalachia. The solicitation of a poem brought immediately to mind nonhuman inhabitants of where I grew up that I’d had salient interactions with—green anoles, so many mockingbirds, a great-horned owl, several box turtles, a couple red foxes, and only a couple weeks prior a whippoorwill.

I’d gone to my office at Georgia Southern University on a Sunday to get a little work done. And as I was leaving, I decided to walk up one flight to the 3rd floor just to get the steps in. The building’s elevator and brick stairwells are on the outside—almost like afterthoughts. As I ascended the stairs, I heard thuds against glass and found a mockingbird and a whippoorwill trapped in the landing that had been glassed-in to keep students from throwing trash onto the roof of the second-story skyway connecting this building with the next. I was able to coax the mockingbird onto the elevator and rode down with it. I grabbed a lightweight bookbag from my office to handle the whippoorwill who didn’t seem to want to ride the elevator. As I bent down to pick it up with the bag, it backed me off when it turned and disappeared its face by opening its unnervingly large and pink insect-catching mouth to hiss at me. It looked like it could swallow me and everything I knew whole. But it needed help, and when I picked it up gingerly, it was like nothing in my hands—so light. It was stressed before I’d decided to rescue it, and I hoped my handling it wouldn’t be the last straw; I begged it not to die as I raced down the stairs as carefully as possible. I placed it in the wood chip mulch behind the groundcover and bushes by the breezeway. Though still breathing rapidly, it seemed to blend in nicely. It was still there and breathing after I came back down from returning the bag to my office. It wasn’t there when I came back with my son after a couple of hours to check on it. There wasn’t a sign of struggle—no feathers or blood. I hope it recovered and flew off to find better leaf litter to hide against and live a bit longer to catch insects on the wing.

I was struck by this encounter, but I didn’t write a poem about it, so when that invitation to write a poem came, I felt I might have one on my hands, but when I got the list of species, L. Lamar Wilson had already claimed the bird, and his fantastic sonnet “Whip-Poor-Will, I” lives in the anthology. Seeing the lake sturgeon among the species left to choose from reminded me of immersing my hand in water to meet that fish on the shore of Lake Superior. To write that poem I needed to find out a little more about the lake sturgeon than how one feels to my touch. I learned that due to human activity they’d been pretty much extinct in southern Appalachia for decades in the 20th century until the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga worked with state and federal agencies to reintroduce them to the Tennessee River. I found out lake sturgeon can live for up to 150 years, and since the sesquicentennial of the U.S. Civil War had just passed, that span of time resonated for me. Getting to know their history, our history, gave me access to my poem “Lake Sturgeon.”

Last year, I was invited to speak to a class about my nature/ecopoems. They were reading Camille Dungy’s field-altering 2009 anthology, Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, and I was to read my poems from that collection as well as new work and answer questions from the students. The teacher anticipated the students might want to know how one manages the tension between sheer immersion in nature versus some attempt at activism or engaging with politics. I think “Lake Sturgeon” may be an example of a poem that goes beyond “sheer immersion” and engages that tension mentioned. Whether or not it’s admitted to, the stance of “sheer immersion” in nature is political and supports a certain narrative. My regard, my observations, of the nonhuman world are shaped by our history—framed by those narratives—and are subsequently political. That’s how we grasp and regard—through the frame of narrative. That’s how we know.