A month or so ago, I met a friend I hadn’t seen in a while for a drink—an ordinary excursion, but like so many ordinary things made strange by the years we’d just lived through, simply to be out in the evening high-tide of strangers in a downtown bar, we both agreed, still felt consequential. We were getting reacquainted; over the course of the pandemic we’d drifted, our communications dwindling from a regular exchange of manuscripts to sporadic text-message check-ins and finally into what felt like meaningful, mutual silence. At one point, I’d wondered if I would ever read her work or even see her again—I had, in fact, more or less accepted that I might not. She’d had a lot of trouble making room for poetry, she said, and had been ashamed. Of course, I understood. Who could account for all the odd effects of those foreboding and seemingly endless years?

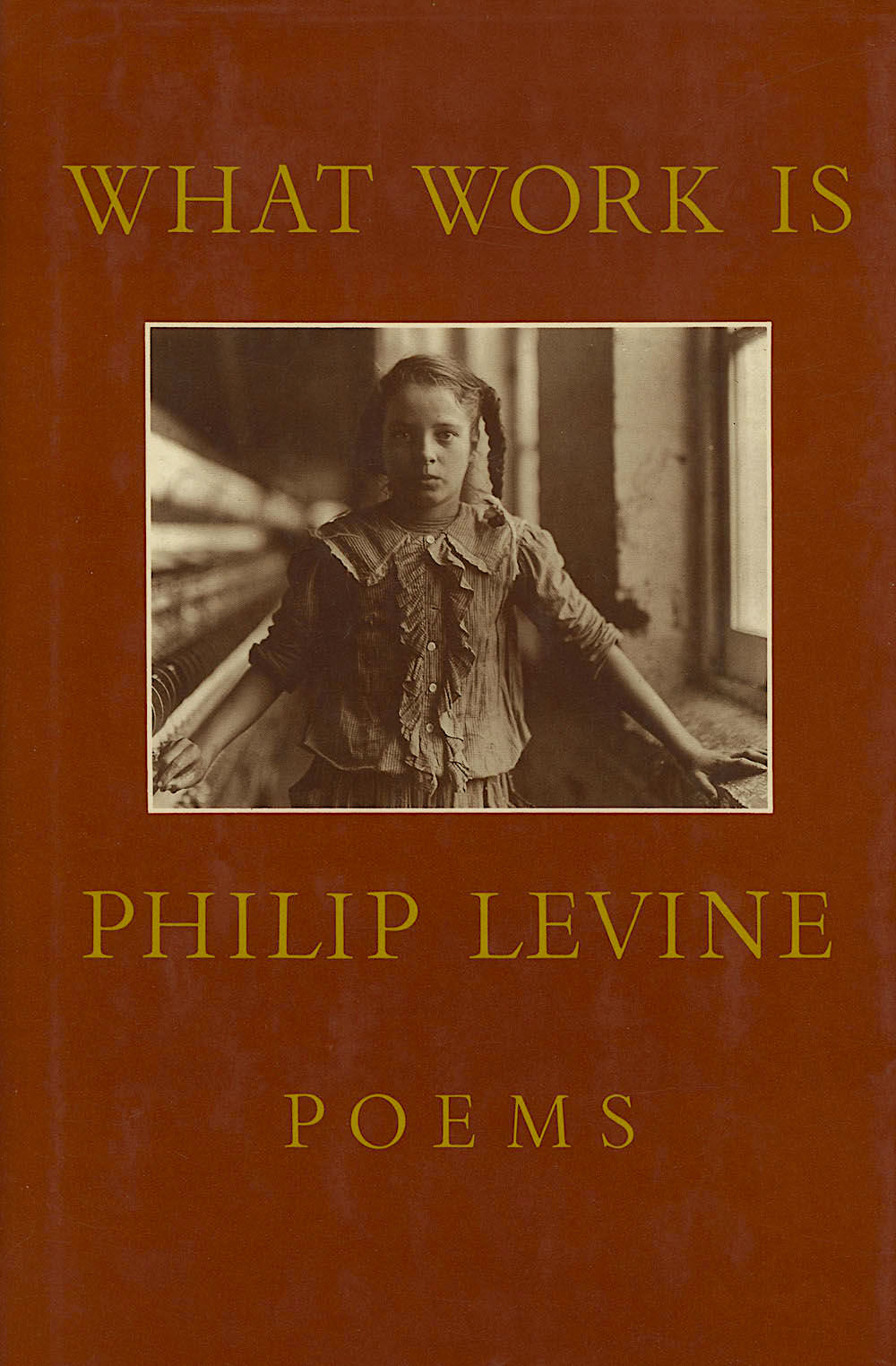

I had been ready to give up on the whole enterprise as well, I told her—for an alarmingly long time, nothing I picked up seemed able to penetrate or point the way, a demoralizing experience indeed for someone who’s always balanced a great deal of himself on an abiding faith in literature. But then I happened to revisit Philip Levine’s What Work Is. In it, as in all great books, I found newness, lines which, though the book had been in the world for more than thirty years, seemed to have been written the night before. Take these, from “Scouting,” a poem that contends, among other things, with the problem of finding a psychic foothold in the immensity of a life and a past and a future, its sensibility equal parts elegy and ode:

You can feel the whole country

wanting to waken into a child’s dream,

you can feel the moment reaching

back to contain your life and forward

to whatever the dawn brings you to.

Yes, I certainly could feel that. Even to my jaundiced eye it read like a perfect condensation of the big feelings of that moment. This is a thing that only poetry can do, I was reminded. “Scouting” and many like it in the book comprise a poetry of awakening, of simple amazement at being alive, at having lived and at the living still to be done, of making meaning out of the morass of experience, time, and trouble. I told her all of this, my friend, as we got into a second round, and then, as is natural for a couple of poets with a couple of drinks in them to do, we pulled up some of Levine’s work on our phones and read aloud to one other. And then we were quiet, just looking out into the dark from the window seat of a warm bar filled with strangers, savoring a moment of deep remembering in the work of a poet we both admire, together again for the first time in a while.