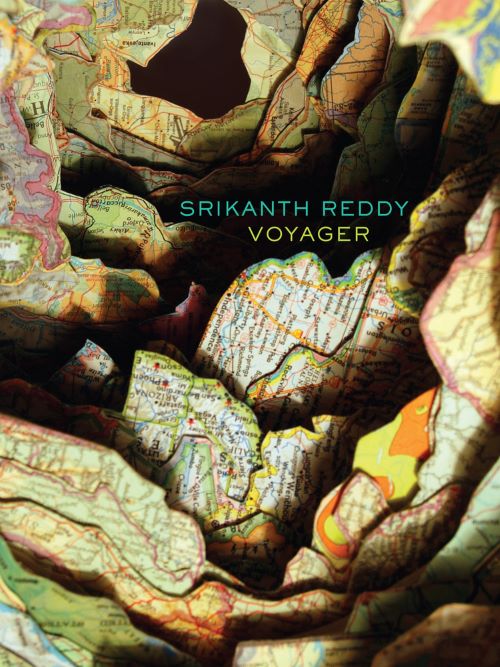

In the late 1970s, Carl Sagan helped NASA collect sounds and images representative of human culture to send into space as part of the Voyager missions. The project was an ambitious act of curation envisioned on a cosmic scale, and the “golden records” are now the most distant human artifacts in the universe. The first voice an alien species would find, though, were they to play the Voyager recordings, is that of Kurt Waldheim, the Secretary General of the UN from 1972 to 1981. Waldheim famously misrepresented his wartime record during his tenure at the UN and was later exposed as a participant in Nazi atrocities. A fitting emblem of human culture, indeed.

In his 2011 poetry collection that shares the name of the spacecraft, Srikanth Reddy offers a three part erasure of Waldheim’s memoir in an attempt to reckon with “the words of a / man who by some quirk of fate had become a / spokesman for humanity, who could give voice / to… the conscience of mankind.” “Sometimes,” as Reddy’s speaker notes drily in the second section of his book, “a work is clarified by ironies.”

Using Waldheim’s voice as his principal constraint, Reddy uncovers the many “alter egos” embedded within the memoir’s self-serving prose. He deftly balances the focus on Waldheim the historical person with a recognition of the more far-reaching complicities of language itself. We sense that the objective, academic diction of Reddy’s speaker is also a form of duplicity, a performance in the “theatres of neutrality,” a way of forgetting where exactly the life ends and the role begins.

Every public persona implies a negotiation between the facts of biography and the imperatives of form. If Waldheim is “fashioned in the assembly of his book,” then Reddy erases the text to recover what’s absent or omitted from the official narrative. Silence and speechlessness become thematically as well as formally a sort of cipher: “the making of the key / that opens the quiet, // turning in the mechanics of fact…” Speaking through Waldheim’s words to reach his silences, Reddy offers us alternate universes that exist alongside, enrich, and unravel the original text. “Silence [becomes] a figure for the infinite,” and Reddy suggests that “under every image” there are “unending regions / of consequence.”

It’s true that in the vacuum of interstellar space sound waves can’t travel. But that doesn’t mean that the silence of deep space is entirely silent. When the Voyager 1 spacecraft exited the solar system in 2012, it recorded plasma oscillations and “quasi-thermal noise” in frequencies perceptible to the human ear. Scientists called it a steady drone or a humming; they compared it to a gentle rain in the background. We still don’t entirely understand the texture of this signal, but it has led some scientists to reconsider the formerly stable categories of sound and silence.

Reading Reddy’s collection, for me, has a similar effect. In repeating Waldheim’s language but stripping back the rhetoric, he insists on a distinction between sound and significance–what’s said and what we can intuit beneath the public performance of language. His poetry offers a lesson in the imaginative potential of erasure and the politics of silence.