Midday. Texas heat. I’m walking up the steps to my garage apartment. In one hand there is beauty, these flowers. In the other is this fish. Dead. Wrapped in brown wax paper by the grocer. Cod. I’ve bought the cold-water fish many times but today the weight of its flesh in my palm is a terror I will not forget.

If it’s true what Don DeLillo says—that stories must absorb our terror—then the terror simmering beneath my skin is American-made. My terror is fueled by questions. What does it mean to be part of a culture where violence is built into nearly every aspect of its identity? What does it mean to watch the deluge of domestic atrocities of white supremacy, police violence, and mass shootings on the daily? And what does it mean to be a person of color in this country? In this moment terror has me examining all I see, hear, and touch—the fish, the flower vase, an insect, the chorus of cicadas that will come later in the evening, as they become representations of power or the lack thereof; as they represent safety or its illusion.

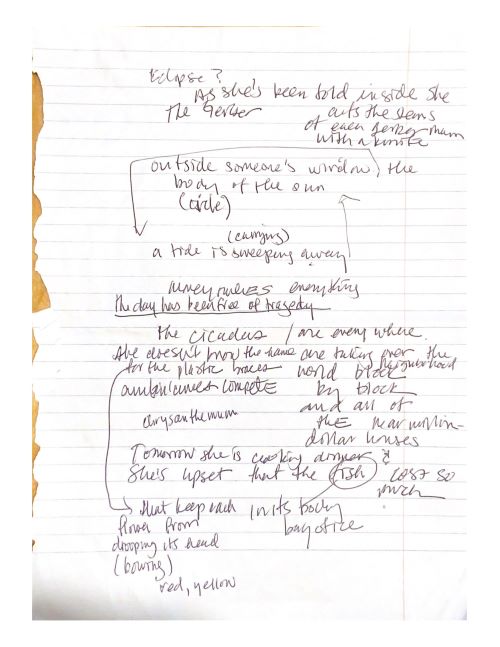

In a notebook—fragments and sentences written in no logical order. Because the poems written up to this moment experiment with third-person, in these notes I refer to myself as she. Perhaps it’s a bias but I believe in any poem, all pronouns, but perhaps most especially I, need to defend their existence. In a first-person centered culture, the use of I is often a reflex action as opposed to an intentional and necessary part of a poem. In these notes, I rely upon third-person as well because its use speaks to our ocular-centric existence. If the poet watches then so too must her reader.

My poems usually take several months, if not years, to write themselves but “Lyric Sung in Third Person” will only take a few short months. I often think cinematically and the poem’s draft is asking me to deviate from the conversational tone of my previous work. It’s asking for a reflective and lyrical treatment. Here, I imagine a canvas filled with lineated images and caesuras in my attempt to engage the visual and kinetic energy of the page.

What will fascinate me most is the way the poem’s ending gestures toward my own potential complicity, which seems a much more nuanced and realistic engagement of power as a subject. In the end, the poem’s language and form are vehicles used in an attempt to absorb my own terror and the reader’s terror—though the story of the poem and the story of the country—is far from complete.