“But the convention is not immutable

and there came a time when the logic

began to fail.”

—Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”

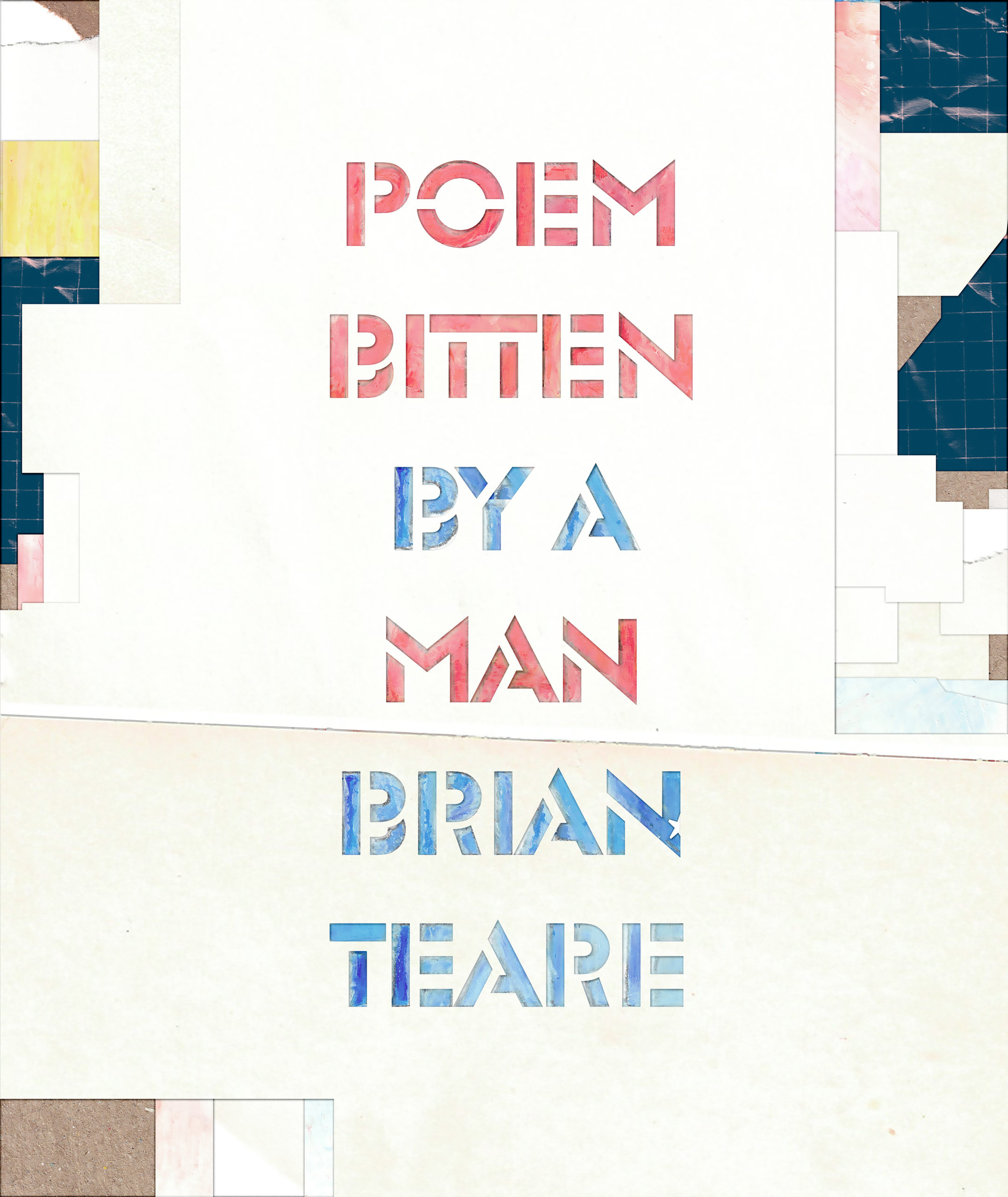

I think of Poem Bitten by a Man as ekphrasis in the expanded field. Official histories and conventional definitions have generally limited ekphrasis to “a description of visual art as a literary device,” but ekphrastic practice today is far more capacious. My work’s informed by the recent innovations of Rick Barot, Eduardo Corral, Carolina Ebeid, Erica Hunt, Fred Moten, Khadijah Queen, Martha Ronk, Evie Shockley, and Cole Swensen. In exceeding the frame of visual description, ekphrasis in the expanded field refuses to dwell only on the surface experience of visual art – or film or dance or music. Going outside of the frame and beneath the surface, it engages with another art by reconceptualizing and recontextualizing it: in its historical and cultural and subcultural contexts, its critical reception, its making and materials, the artist’s biography, the poet’s autobiography, the creative process of ekphrasis itself, or any other framework that seems relevant.

While writing Poem Bitten by a Man, I watched a documentary that included an interview with Robert Rauschenberg, who was filmed, I think, perched on a step toward the top of a very tall ladder. Issuing pronouncements from on high, he sounded both flip and pompous. “You can’t make life or art,” he said, “You have to work in the gap between.” Though I don’t generally subscribe to edicts, that is one place to find the expanded field, in the between, in the gaps: between life and art, poem and painting, word and thought, hand and eye, object and process, individual and collective, materials and concept, etc. In my own practice, I insert the notebook in the between like a filter and let it catch the language that passes through that gap: little snippets of art criticism, biography, image, the artist’s own spoken and written voice, material detail, all intermingled with language from my own life. Expanded ekphrasis might contain descriptions of art, but ultimately offers it in order to build a deeper encounter with making’s many sites: culture, community, history, love, home, life.

What most draws me to abstract painters is the play between the specific physicality of their processes and the quiddity of the objects they leave behind. In this, they are like the poets I most admire, whose poems grow directly from the old root that means to make. To watch a painter at work reveals their poetics; their brushstrokes perform a tacit theory of making. I watch Agnes Martin, for instance, who wants brushstrokes discreet and without drama. She carefully draws her brush down a canvas hung from its side so that the direction of her brush and of the watered-down acrylic follow in the same direction between graphite lines she measured and laid down with a ruler. Watching her at work in Mary Lance’s documentary, I understand the true extent to which this painting has been pre-determined, and how Martin’s craft is about realizing precisely and accurately a painting she has seen in her mind. Once she has the math of its proportions worked out – the hardest part for her – it doesn’t take too long to paint it.

Poem Bitten by a Man records sustained meditations on the work, writing, and lives of Martin and Jasper Johns, two queer abstract artists, but it also details briefer engagements with Eva Hesse, Sam Gilliam, and Bay Area legends Ruth Asawa and Jay DeFeo. Though these engagements are more brief, they are not less intense. When I saw DeFeo’s retrospective at SF MoMA, I’d lived in the Bay Area for over a decade, so the myths surrounding her and especially her painting The Rose, preceded my first firsthand experience of her work. But the artist I met through that exhibition had, of course, made work both before and after the painting to which her career is too often reduced. In fact, except for the six infamous years she spent painting The Rose, DeFeo exhibited an ingenious ability to hone in on the gap between life and art and work from there.

When I saw her retrospective, I was three years into an acute health crisis and looking for ways to keep going as a person and as an artist living with chronic illness and pain. Was I feeling sorry for myself that day? My notebook doesn’t say. What it does say is that I fell in love with DeFeo’s work, and especially with two series she made in the wake of invasive, expensive dental surgery. The first, Crescent Bridge, begins with a photographic study of her bridge and then moves on to two landscape paintings. The second, September Blackberries, also begins with a photographic study, this one of an arrangement of teeth, which then transforms into a still life. Both series begin grounded in a difficult economic, bodily, medical reality that DeFeo abstracts via close study into forms – crescents, blackberries – and genres – landscape, still life. In doing so, she makes a difficult reality plastic, a material with which to work.

In much of Poem Bitten by a Man, I aspired to make in my poems the transformations of difficult experience DeFeo makes in these two series, even if I could not always face my own economic, bodily, and medical reality with the same ingenuity and good humor. But “This page is for Jay DeFeo.” has a different aim. I wrote it like the rest of the book: by collaging material from notebook entries, visual description, monographs, interviews, and relevant art criticism. But in cutting it all up and pasting it together, I wanted to build a valediction of her work, which offered a profound source of comfort, and her life, which urged mine to keep going. I wanted to offer a tribute to her specific touch, at once delicate and tough. I wanted to reproduce what I could of the “the construct-/destruct feature” particular to her vision, which has a compelling integrity entirely its own. But most of all I wanted to say: thank you, Jay.