In 1897, a twelve-year-old boy named John Mullahey from Peekskill, New York walked out of his home, disappearing from the lives of his family, which included his younger sister Mary, who searched for him for more than forty years. Or at least that was where things stood in 1941, when Mary placed an ad in the Missing Department, a missing person column published in Western Story Magazine.

We’ll never know why John felt the need to disappear, or what his vagabond teenage years looked like, or if Mary ever saw her brother again. Instead of answers, we’re given only this glimpse into one woman’s sense of loss and confusion, commemorated by a small handful of words that appeared in a pulp fiction publication more than eighty years ago.

My wife and I first stumbled upon the Missing Department in the waning months of 2020. Like so many people across the world, we felt isolated and afraid for our friends and families as the COVID-19 pandemic raged on. We drifted through those reeling days, trying to find ways to navigate daily life. I found it difficult to attend to my own writing, and my wife, the visual artist Ligia Bouton, hadn’t been able to sustain any regular studio practice. On a rather odd whim—this is, admittedly, a little difficult to account for—we ordered a box of western pulp fiction magazines from eBay, hoping that we might find something in those battered issues that would inspire a collaboration and fuel our creative lives.

When the box of magazines arrived, we sat in the living room and flipped through the pages. To be honest, my first response was disappointment. I didn’t see anything very compelling in Western Story’s artwork or fiction, which I found to be predictable, crammed with stereotypes, and, on occasion, pretty damn racist. It was Ligia who first saw the Missing Department and that ad written by John Mullahey’s sister. “Come look at this,” she said.

Once we both started looking, it was difficult to stop. We read about estranged lovers, chance encounters, missing spouses, AWOL soldiers, and children desperate to reconnect with their parents. There was an ad placed by Speedy, who was in trouble and needed help from Cleo, a dancer with the Bernardi Circus. A woman named Gertrude succinctly declared “Martin—The children need your help.”

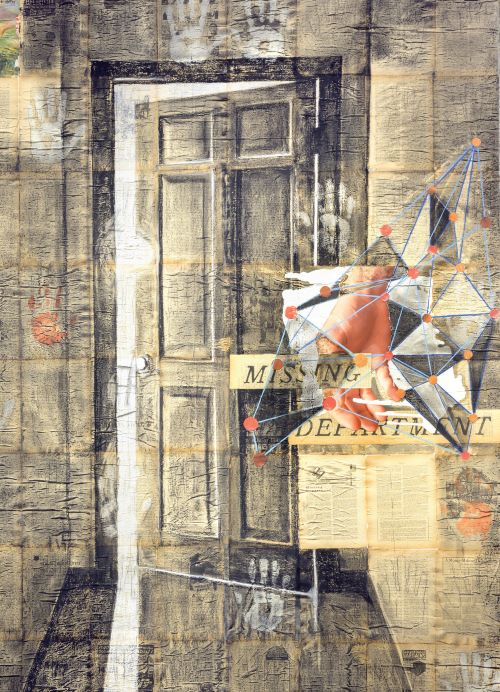

The text of these ads suggested whole worlds of loss and desire deployed with the brevity of haiku. Unlike the magazine’s fiction in which, without fail, the good guys always won, the Missing Department offered messy fragments of human need that remained forever unresolved. As my wife and I poured through the columns and ordered more copies of Western Story (as well as Detective Story, a sister publication, which also featured the ads), we began to hatch a plan for a project. Together, we would choose an ad that we both found resonant. We’d then divide the magazine between us and respond to its text through our different mediums. Ligia would make visual art that somehow made use of the magazine’s original pages, and I would write a poem using blackout poetry techniques applied to a single work of fiction. Although we’d work separately, after each piece was done we’d reconvene around the kitchen table to share what we’d made.

For both of us, there was something resonant in exploring these stories that had been, for all intents and purposes, in themselves lost to history. It struck us that a few short sentences could be the only remaining historical record of Thomas James Brennan, who may or may not have been killed in the trenches of France in 1918, or Lester Daubley, who had once been given a handkerchief containing the address of a girl named Alberta. It was also impossible not to read these missing person ads through the lens of the COVID pandemic. Just as so many of us experienced in 2020, here were the voices of people who felt isolated from their loved ones and uncertain about what the future would bring. Here was a long cascade of “I”s calling out to absent “you”s.

Not all of the ads placed in the Missing Department were freighted with emotion, though. Given that the column saw its peak popularity well before the proliferation of telephones in most homes, it was frequently used as a means of direct communication. Having tracked down decades of these ads, we encountered plenty of pragmatic queries (an adopted son seeks a birth certificate from his biological parents in order to be promoted as a wireless operator in the navy), enigmatic riddles (“Static, times are quiet now. Always, Beetle”), and lists of folks whom various foreign consulates were trying to reach.

In a June 26th, 1929 issue of Detective Magazine, we also came across the following text: “Floy—I never requested such things to be printed. I will be here all winter. Please write and let me explain. Mother, 435 Jefferson Street, Klamath Falls, Oregon.”

We had some questions. Unlike so many of the ads in which the author was seeking to be reunited with someone, “Mother” seemed to be looking for an opportunity to justify her actions amid an ongoing argument with her son. Yet this exchange wasn’t heated, and beyond the enigmatic nature of the core complaint (what, indeed, had been printed and where had that text appeared?), we found the mother’s tone, diction, and syntax carefully orchestrated. The use of the word “requested,” for instance, seemed to defer blame. In lieu of any admission of guilt, there are undercurrents of self-righteousness and indignation, and any fleeting tenderness summoned forth by that “please” is offset by Floy’s mother’s insistence that she’ll be waiting for his response all winter, slyly suggesting there’s no excuse to not be in touch. Far from apologizing, Floy’s mama is demanding an audience.

Or at least that’s how I saw it as I started thinking about the blackout poem I might write by rummaging a story called “Signals and Shadows” which, per our project’s rules, appeared in the same issue as the published ad. From the outset, I was drawn to the suggestive nature of the title, which seemed to correspond to the mother’s strategies of opening a door to conversation while simultaneously ducking free from blame. As I skimmed through the story about a detective trying to stop a home burglary syndicate, I noticed two lucky coincidences: a subplot involving an invalid mother, and a small detail that involved “printed” business cards.

Yet, as with each of the blackout poems I wrote for our Missing Department project (twenty-five in all), there were always more resonant and unexpected meanings to explore beyond any words the two texts happened to share. Although I might have been initially pleased to make a connection between the mother’s address in Klamath Falls and the story’s descriptions of a river that ran through the center of its fictional town, for instance, the presence of moving water ended up affording me the poem’s core metaphor. As I tried out different phrases during my drafting process, stumbling upon the idea of a river sloshing through a signifier was an unexpected pleasure, and ended up unlocking the poem. I loved how the water revealed itself as an uncontainable force, and perhaps spoke to the surging currents that run through both language and relationships. I also loved how the resulting piece—from its circular structure to the strange hissing neologism of that “Sh-s-s-s-s”—was not something that I ever could have written had I started with a blank page.

All of that said, I see my resulting poem as just one possible response to the lines written by Floy’s mother, and one that isn’t intended to supersede the original ad. Had I chosen a different story from which to remove text, I would have been led down a vastly different path of image, voice, and metaphor, simply by virtue of the available words. For that matter, Ligia’s visual art response offers a different kind of engagement from my own. In Ligia’s piece, I love the way the woman’s face hinges back to reveal stacks of words pinned into place like insects under glass, and how the use of pins offers both pearl-like ornament and an easy means of jabbing anyone close.

Throughout this project, our hope was to create a resonant dialogue by having all three pieces—Ligia’s art, my poem, and the missing person text—in conversation with each other, and to treat our creative responses as an invitation for empathetic engagement with these lives. At the peak of its publication run, each Missing Department column included close to a hundred ads, meaning there were always more words of desire and loss to wonder about and chase after. Just a few ads later, for instance, someone is looking for W.H. Sheppard, who has a scar from his time in Canadian lumber camps, and whose father is recently dead. And then there’s William John Hunter, seeking information about Lucy McCrady simply because, as he puts it, “she is a friend of mine.”