A Barcode ScannerTent block, then muddy street, then tent blockIn the beginning there was the number and the number became a price tag stuck to usThe number made our selection easier from afar, no need to pointThen the earth became a radio with an eternal battery, no broadcast station, and no stop to the disruptionMuddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetWe raise ourselves on the hatred of death and the love of the deadWe raise ourselves on the love of life and the hatred of the living!The crazy nobody is singing while teenagers chase him, trying to strip off his pajamasTent block, then muddy street, then tent blockThe IDP is a zebra in a fenced-in wildernessBrowsing the statuses of a closed Facebook groupMuddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetMay your eyes cloud over and the peacock’s corpse become your eyepatch, deviant pirateThe prayer of hungry mothers, boiling boredom for their children, who snore through midday in every tentTent block, then muddy street, then tent blockWho introduces the IDPs to sunrise?Who convinces them that the sun serves any purpose but heat?Muddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetThe wind in your tent is just an ascetic Sufi mocking you with each whirlTent block, then muddy street, then tent blockWith his ration card held tight in his extended handThe IDP walks along the streets searchingLike a mine detectorMuddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetA tomato vendor: If only there were a tomato festival, so that people could learn to associate the color red with something elseTent block, muddy street, then tent blockAn onion vendor: Long live life!An eggplant vendor: Ha ha ha!Tent block, then muddy street, then tent blockLife in the camp is encrypted despair, but the IDPs are not hackersMuddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetTent block, then muddy street, then tent blockMuddy street, then tent block, then muddy streetERRORERRORERRORDear consumer—Could not identify the producer of war! Life from AfarWith two emoji hearts we loved each otherWith two pictures we proved our empty presenceWith two steps backwards we got closerWith two keyboards we thumbed a bed and poked the darkWith two calls we befriended silence and learned to groanWith two lips that kissed nothing but their pair on the screen we locked in a virtual embraceWith two orgasms separated only by a sperm’s suicide we broke like a waveWith two fucks from afar we bore a dollWith two mutual lies the three of us are now a happy familyAnd every day you are the army that kills meI’m the last sparrow on the world’s tree

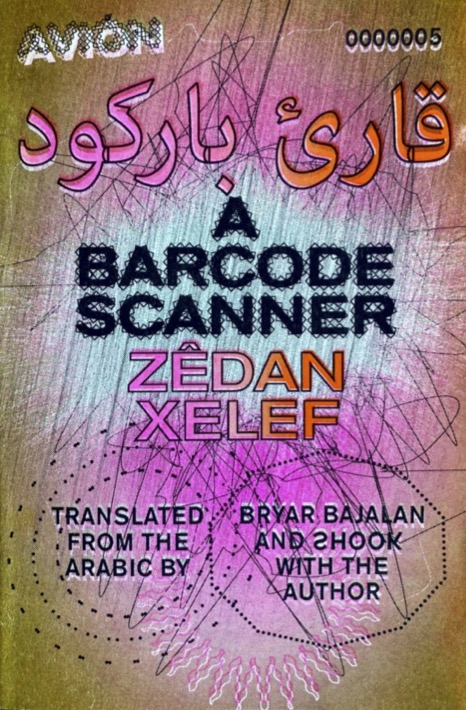

A Barcode Scanner (excerpt)

Feature Date

- December 15, 2023

Series

- Translation

Selected By

Share This Poem

Print This Poem

Copyright © 2023 by Zêdan Xelef

All rights reserved.

Reproduced by Poetry Daily with permission.

Zêdan Xelef was born on Shingal Mountain in northern Iraq, in 1995. Displaced from his home by Daesh’s attempt to exterminate the Êzîdî, he arrived with his family to the Chamishko IDP camp in late 2014. He studied translation at the University of Duhok, and his current projects include translating Whitman’s Song of Myself into Kurmanji and a selection of poets from Rojava into English. His poems and translations have appeared on Harriet (Poetry Foundation) and Words Without Borders, as well as in Asymptote, Epiphany, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Plume, Poetry London, Tripwire, and World Literature Today. Today he is an MFA student at San Francisco State University, and contributes to ingal Lives, an oral history project based at Kashkul, the center for arts and culture at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani, where he manages a team of Êzîdî young people dedicated to collecting and preserving their culture’s endangered oral tradition.

Eric Curtis (Shook)

Bryar Bajalan is a doctoral candidate at the University of Exeter, where he researches depictions of eroticism in the poetry of Mosul, before and after Daesh’s occupation of the city. His work has been published Hyperallergic, Modern Poetry in Translation, World Literature Today, and on the Poetry Foundation website. He recently completed a short documentary about early twentieth century Baghdadi poet al-Zahawi. Together with Shook, he is translating a book of poetry by contemporary Sudanese poet Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi, forthcoming from the Poetry Translation Centre in 2023.

Shook is a poet and translator who lives in Northern California. Their recent translations include Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi’s A Friend’s Kitchen, cotranslated from Arabic with Bryar Bajalan, Mikeas Sánchez’ How to Be a Good Savage and Other Poems, cotranslated from Zoque and Spanish with Wendy Call, and Conceição Lima’s No Gods Live Here, translated from Portuguese. Shook’s film A Barcode Scanner, based on Zêdan Xelef’s poem by the same name, won the 2020 Best Film for Tolerance Prize at the ZEBRA Poetry Film Festival in Berlin.

In stark, contemporary language that bears the influence of the Êzîdî oral tradition, the poems in Zêdan Xelef’s debut offer a searing indictment of the commodification and dehumanization of the displaced. Translated from the Arabic by Bryar Bajalan and Shook, A Barcode Scanner’s wide cast features IDP camp managers and UN representatives alongside literary forebears like Anne Sexton and pornstar Sasha Grey, in poems that recount tragic camp fires, text message romances, and the drudgery of everyday life for the survivors of Daesh’s 2014 genocide of the Êzîdî.

Avión, named after Mexican estridentista Kyn Taniya’s 1919 book by the same name, is a new project that seeks to promote the innovation and internationalism espoused by Mexico’s historical avant-gardes, creating a transportation, a flight if you will, in between landwatches mostly from other languages into Spanish but also across inter-pollination of different emancipatory imaginariums, furies, directions and tongues.

Poetry Daily Depends on You

With your support, we make reading the best contemporary poetry a treasured daily experience. Consider a contribution today.