Disabled Sonnets Go to the Café and Write about Death

Let’s investigate a deformed sonnet. Are you taken aback by this stigmatizing language? Deformed, disabled, ruptured, sprawled: let’s play a bit with these words as I share my disabled poet’s thoughts on how a poem about location and memory comes to find its form.

Read the poem “Split/Screen.” Look at it, count the lines, mouth it. You wouldn’t think it’s a sonnet, because it isn’t. No fourteen lines, certainly no end rhymes, no volta. And yet, if you squint at it, you might begin to see that it has an origin in this conventional form.

I wrote the initial freewrite for this piece in a Detroit café. I am an observer of city life by dint of my painful bodymindspirit and my need for rest. This is my poet’s working method: I wander and drift slowly through a small section of the world, in urban or rural sites. Then I sit down (in a café, or on a log when I am out and about with my cane, or else I just sit back in my wheelchair). I let the world influence me. Words appear. In revision, I squint at the emerging lines.

In the case of “Split/Screen,” the magic structuring principle of “fourteen” hovered in my brain. The sonnet is a device I often use, not necessarily as a formal frame but as a couplet structure to hold against my freewrite. This offers a scaffold toward something that can spread out on the page and take up space in the world.

Contemporary virtuosos of the poem do amazing things with this structure. I love Diane Seuss’s Frank: Sonnets, where the form takes me on wild rides through art, cottages, fairy tales, and poverty, metabolizing a self/history mélange that leaves me spinning, breathless on the golden couch by the wood burner. Seuss begins one of her pieces “The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do/without.” (117).

My unruly non-sonnet is not good at leaving bits out. It does not adhere to Lorine Niedecker’s condensery tradition: a distillation of thoughts and images into concision. So here and there, my non-sonnet sprawls, or limps out of line, like I do as an embodied being in the street. I hover in the slash, the “/.” I like that unruliness, the indecision, but also the tough embrace of the honing, the clasping, of holding words dear and pressing them to see which ones I can lose so that I can hold the rest even closer.

Out in the world, my disabled bodymindspirit rescues itself with a cup of coffee, watching the city go by, at times with sadness and bodily pain. I would like the absinthe I write about in my poem, but my medication won’t allow it. Instead of walking quickly with purpose toward a future, I just sit. But through writing, I become differently mobile in the city when I hunt the past and the present, and catch them on the page. Past and present are “verschränkt” (loosely translated as “interwoven”), my German memory wants to say. They are “entangled,” my Anglo contemporary cultural material theorist self wants to echo. Who traps whom in forms?

Poems emerge when what is in front of me — the street — glides into my past experiences. Moments of self get caught up and shift with cultural worlds, worlds like cinema and TV. “Split/Screen” remembers old cinema clips, like the Hindenburg zeppelin burning, and the flashing lights of contemporary police procedural serials.

The cinema becomes part of Canadian poet Roxanna Bennett’s sonnets in Unmeaningable where Bennett writes in the isolation of sickness. They repurpose Hannibal Lecter, the incredibly cinematic cannibal/anatomist/gourmand, into their sonnet crown’s addressant. Engaging Hannibal is their way of getting out into the world. Bennett finds in the screen monster an ally against doctors, railing against both systems and pain: “Hannibal, let’s hunt white coats” (53).

“Split/Screen.” The title of my poem also leans into fantasies of the big screen with its metaphors about the workings or non-workings of memory, or the wholeness or fragmentation of bodies. And the sonnet, this corseted form, can hold things for a while, like a body under assault, holding its insights in. But in my deformed sonnet, language spills out in the middle, spills through the careful assemblage. Right in the middle of the ordered couplets, a pressured speeded-up movie runs over my tongue, onto the page.

With Bennett, I find inspiration in cinematic vision machines, and in the intertwinement of horror, visuality, and the wholeness of the human bodymindspirit. I am writing with the flaneur writers of Weimar Germany like Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer, who wrote about history and change while sitting in arcades of glass in a modernist Berlin. I am an ecopoet, and I drift in sites (and teach classes like Eco-Imagination and Cinema and Queer/Trans Eco Arts). Precarity, assault, and the police procedural are all part of the urban ecopoetry genre and find their way into “Split/Screen” and its spilling.

“Split/Screen” is a poem with a broken creature, blood, and a scar. One way of narrating the personal content of the poem is that it is “about” memory loss, and a strange kind of floating body horror.

Here’s the personal story I tell when reciting it. As a student, I was touring with a choir in North Germany. One night, we were driving from one cathedral city to the next when we hit black ice on the autobahn. Our car catastrophically spun out, took flight, and flipped. While we all survived, the driver broke his neck and had a long recovery.

And me? I remember flashes of the car turning, a white comforting light, and glimpses of bright color and bloody glass. Then I woke up in a hospital bed. Someone with whom I had a sweet one night stand after the prior choir gig was kind and took me home. I stayed a few weeks in Hamburg, and we drifted together in the night with eye-make-up and club clothes, like queer birds of paradise. Scars healed, but I lost over a year’s worth of memory. It was only very recently, over twenty years later, that a German friend reminded me where I had actually lived (in Cologne) at the time: I had completely forgotten the flat, its location in the city, my flatmates, my job. I never found my way back after the accident; my stuff was thrown out. This is a story of modern lives, without trace or tracking.

That’s a story I can tell with a smile. My voice glides over precarity, terror, the death wink. But a poem is a not a story, and the chop of a form like a sonnet can hold horror. How can a story like that become a trace in a poem, or the beat behind it, opening to something too large to contain, breaking through?

In Terrance Hayes’s American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, one of the poems remembers Rilke and James Wright, a black detective’s family, the African American Folk Museum, and then shots that burn through and query what is valued and meant as “life” (37). Every line in Hayes’s collection begin with a capital, slicing up grammar and sentences. The sonnet cuts and squashes. Hayes writes into a racist past and present, using the sonnet form to articulate the biopolitical question of who is deemed worthy of life.

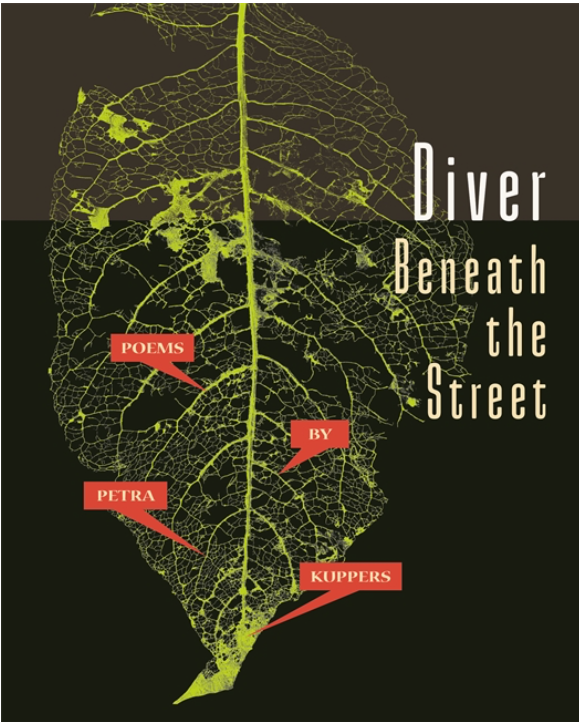

In my collection, Diver Beneath the Street (which houses the “Split/Screen” poem), many of my drift landscapes are murder sites in Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor, and Detroit, sites where women were brutally killed. “Life” is the issue here, too. Who gets to live, in which ways, who is controlled by colonial powers, by racist, misogynistic, transphobic, classist, and ableist value schemes and land use practices, by medical establishments and their dicta about whose lives are worth saving? What does a life consist of when memory fails or flails?

“Split/Screen” holds one moment of my own life/death. It’s in a book that uses drifting as a means to live on in murderous sites, to see detritus and decay transformed by beetles, worms, the soil itself. What is left when the emergency lights are gone? A deformed time river. Lights on snow, wheels turning.