I met Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi in 2012, when I was the Translator in Residence at the Poetry Parnassus, a weeklong event at London’s Southbank Centre featuring a poet from every competing Olympic nation. As one of his nation’s most beloved poets, Al-Raddi was there to represent Sudan, and we were introduced by his late translator Sarah Maguire, the founder of the Poetry Translation Centre. While Saddiq represented his country in the United Kingdom, 22 of his colleagues at the national newspaper Al-Sudani, where he worked as Cultural Editor, were fired and imprisoned on political charges by the dictatorial regime of Omar Al-Bashir. What Saddiq had expected to be a weeklong celebration of his people’s poetry abroad turned into a permanent exile from his homeland and almost five years of separation from his wife and children. As he began to realize the permanence of his exile—that he would not be able to return to Sudan for the foreseeable future—he hardly slept. During his late nights awake in London, he would write brief, poetic, often stream-of-consciousness texts to post on Facebook, his primary means of communication with his colleagues and friends in Khartoum. After composing several dozen of these texts, it dawned on him that they were actually poems themselves, and he compiled them to begin his rigorous editing process to prepare them for publication.

The poems are not unlike his previous work, but express the poet’s mysticism at a new, heightened level that often makes them difficult to entirely understand, an aim that Saddiq himself has encouraged me to abandon. Part of their complexity arises from their reflection of the simultaneous spiritual incomprehensibility and physical reality of Saddiq’s exile. Poems like the three-part “121,” resonant with the melancholy of recent exile, recall classical Sufi poetry, contemporary English-language poetry, some of which Al-Raddi himself has translated into Arabic, and the Sudanese tradition, almost entirely novel to an English-language readership. The poems incorporate a wide range of references from both his new environment, where he waits on a night bus behind schedule, and his beloved home, with its mosques’ flags flapping against the city’s dusty sunset. They are heavily influenced by Sufism, Classical Arabic poetry, and Qur’anic commentary, obliquely referencing the Sufi martyr Al-Hallaj—who was killed in Baghdad in 922 CE for, among other things, declaring “I am the truth”—in the third section of “121.” Al-Raddi sometimes proclaims his own, even bolder statements: “Your mouth is the mosque where my lustful mouth worships.” He writes to his son about what his future might hold. He addresses the challenges of communicating across languages, ultimately celebrating the power of a friend’s love to overcome linguistic barriers. Glimmers of hope peek through the darkness of exilic twilight, especially when Al-Raddi writes of love and friendship.

Saddiq and I began discussing the translation of this set of poems in late 2015, meeting several times in London and regularly communicating over WhatsApp to discuss the project. In the early summer of 2018, Bryar Bajalan and I began workshopping our first translations, first over Zoom and later in person in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Working closely with Saddiq, we developed an intimate process of co-translation across continents. Starting with Bryar’s initial cribs, we returned to the Arabic together, experimenting and reworking the transfer of some poems’ complicated syntax into English and unpacking the poems’ many allusions. Because of our close relationship with Saddiq, we were able both to clarify imagery specific to the Sudanese context and to seek his approval for some of the bolder leaps we hoped would make his poetry sing in English as it does in Arabic. Recognizing the uniqueness of contemporary Sudanese poetry, we sought to retain the characteristics that we believe make it distinct: its embrace of ambiguity, the patterns of repetition that reflect its oral roots, and its sudden leaps.

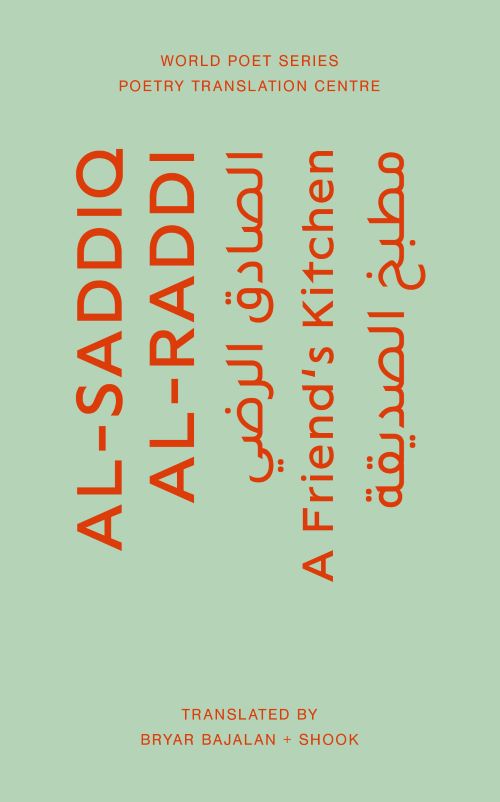

During an era that will be defined by how we as nations, as individuals, and even as a community of writers and literary translators respond to the migration crises before us—from the children caged along our southern deserts here in the United States to the crowded rafts of Somalis intercepted in the Mediterranean, from the Yazidi communities fleeing the Islamic State to the Syrians pouring into Turkey and Burundians into Tanzania and Rohingya into Bangladesh—Al-Saddiq Al-Raddi’s essential voice must be broadcast as widely as possible. Not just one of his own country’s most important living poets, he is also one of the African continent’s most indispensable voices today, and A Friend’s Kitchen is but one small gesture towards redressing the egregious absence of literature in translation from the African continent, while also championing an ancient but relatively unknown strand of Arabic-language poetry.

In late 2019, while producing a documentary in Baghdad about the early contemporary Iraqi poet Jamil Sidqi Al-Zahawi (1863-1936), Bryar and I sought out the opportunity to visit Al-Hallaj’s tomb. Down a blind alley, in the shadows of the city’s hulking Sheikh Maruf Cemetery, a middle-aged woman and her young daughter directed us toward a small structure adjoined to the house where her family has resided for generations, tending to the martyr’s humble tomb with the spare dinars left by visiting pilgrims. She unlocked the door to a chamber bedecked entirely in green—from the sura-embroidered velvet draped over the cist itself to the peeling seafoam of the ceiling’s petite dome and even the empty jug perched on a water cooler standing awkwardly beside the door. Standing before the hallowed remains of Al-Hallaj, I immediately thought of Saddiq, and wished that he could be with us to pay his respects to our mystical forebear. As I reflected on Al-Hallaj’s life—and cruel death, for challenging the social order of an authoritarian regime—it dawned on me that even a millennium later the truth beneath the robes remains as threatening as ever to the oppressor.