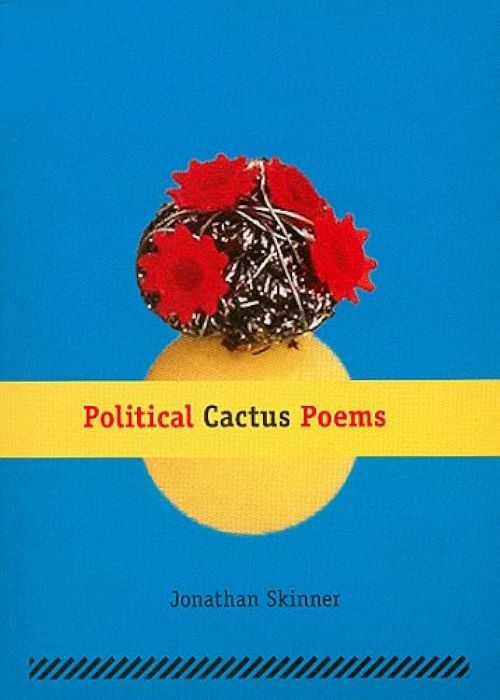

“Unfolder,” written sometime in the late ‘90s and included in my first book, Political Cactus Poems (2005), was sparked by reading a newspaper article about a forest fire at the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) sanctuary in Michoacan, Mexico (I must still have the clipping somewhere), triggering memories of my own visit to the sanctuary a decade earlier. I had been in Mexico on a ‘gap year’, with money saved up from working as a bike mechanic in Boulder, living in a hotel in Morelia with my manual Hermes typewriter, reading Borges and Nietzsche and Paz and Valéry and Melville, and doing my best to learn to write.

Somehow, whether by word of mouth or a tourist guidebook or perhaps by sheer accident, I learned about the monarch sanctuary. One day I made the trip. It must have involved a bus ride. On arrival in Zitácuaro, no gift shop village greeted me. A swarm of boys offered their guide services, but I forged ahead on my own—one particularly persistent boy tailing me to the top of the mountain. I remember his annoyance at my stubborn rejection of his services. I was living on very little money at the time.

With no guide, I had to guess when I reached the roost. I wasn’t sure. I had entered a grove of what looked like diseased trees, branches heavy with clumps of dead leaves. The mountain air was chilly, the low late winter sun hiding behind high clouds. No monarchs to be seen. I was starting to think that perhaps I should have engaged a guide. At which point, with no warning, the clouds withdrew and sunlight illuminated the grove.

What were gray leaves began to flex and twitch and open their wings, detaching themselves from the clumps and launching into the warming blue sky, which was soon filled with thousands of monarch butterflies, hoisting their orange windowpanes. The air was so thick with monarchs I could reach out and grab them. Everywhere I looked, monarchs collided, clasped, fell to the ground in a copulating embrace. Some lifted off again, some lay on the grass twitching. The air was heavy with the sticky sex of monarchs. I lay down in the warm sun . . .

I was completely alone there (or was I) and my narrative will keep it that way.

I can’t remember whether I solicited work from Kevin Killian, or whether he sent something in response to the open call, for the first issue of ecopoetics (2001). Either way, his “Kona Ad Spray Campaign” (an early draft of material for the 2012 novel Spreadeagle) remains one of the contributions to the journal I was least certain of at the time and am most proud of in retrospect. In it, the speaker narrates his entanglement with Gary Radley who with his brother is marketing a fake “Kona Spray” remedy for AIDS. (In the novel, the snake oil plays a part in the death of Sam D’Allesandro.) The narrator and Radley open a box of new publicity for Kona Spray and, like characters with a suitcase of money from a heist movie, throw the brochures at one another:

I wanted to make love on top of them, in homage to the films in which men and women, flush with casino winnings or larceny, express themselves by fucking on money. Like Audrey in How to Steal a Million. I shucked off my running shorts and pulled my cock out of my Calvins, holding it out and dousing it with Kona Spray. . . . When two people are bonded together the way I was to Gary Radley, the younger one doesn’t even notice many details which are bound to get him into trouble later. What I loved about him was his sternness and seriousness of purpose. And also the pale bed of dark hairs on his chest. His ambition. The way he had that Alec-Baldwin sleepy eyed hooded look, like a cobra, as though he never fell asleep, just kept watching while his mouth stertorously continued to breathe and sag. While he was fucking me I felt like the rope the snake inches up and disappears into the sky. He could do it real good and still keep a hand busy on the calculator, adding up columns of figures while spritzing my neck and shoulders with Kona Spray, with long hot kisses that left bruises days afterwards.

I remember asking myself about the piece’s connection to ecology and just knowing, intuitively, that “Kona Spray Ad Campaign” hit the right note, “Kona Spray” a fitting image for the nature writing that had occupied much ‘ecopoetry’ to that point and that my journal hoped to displace. The piece was also raunchy—a first issue of the magazine would have been a failure without some sex in it, which Kevin dished out in inimitable style. Kevin would sometimes remind me, in later years, how grateful he was to have work included in ecopoetics—that before that moment he had never imagined he would have anything to contribute to environmental writing. I’m not sure ecopoetics ever lived up again to the ‘adult’ rating Kevin set for the journal in the first issue, and I’ve often wondered (before and since) at the lack of sex talk in ecopoetics.

It’s not for want of examples—there’s a lot of eros in the poetry constellated in and around ecopoetics these days, and not just in the diverse and flourishing area of queer poetries. I may not myself be well-positioned to articulate why all ‘eco’ desire is queer, but a non-anthropocentric eros, if there is such eros, certainly entails decentering desire from the heterosexist gaze, if not from the gaze altogether. (Current trends in sex therapy around moving desire away from visual stimulus and toward ‘sensate focus’ seem to agree.) Does sexual desire necessarily entail other humans? Can humans connect with sexual energy, as it manifests across a full-spectrum rainbow of ‘naturally selected’ possibilities, without anthropomorphizing or exploiting it?

I won’t claim that I was asking, or even aware of, these sort of questions when I wrote “Unfolder,” nor even that it’s a sexy poem (not for me to judge), maybe it’s a kind of gross when you think about it, but it would be disingenuous to discuss the poem and its contexts without mentioning sex. Or without, at the very least, addressing lepidopteran sex. Did you know that monarch butterflies never complete their migration (not even their children, nor their children’s children)? Only every fourth generation enters diapause as temperatures cool and continues all the way south to the mountain sanctuaries to enter hibernation. And only when spring sunshine warms them again does this generation have sex and move back north to lay eggs for the first generation of the new life cycle.

That sense of completion, of onward life in the “little death” of the individual monarch, certainly is sexual, if not Romantic with a capital R, but I think the poem downplays individual subjectivity, and therefore monarch as metaphor, to instead focus on swarm being. There’s a cosmological or even psychedelic sense of participating in a “universe of monarchs,” but the poem isn’t interested in universal experience. On the contrary, it seeks the value of the partial, “one/ leaf journey’s length”—not quite the “becoming-animal” that philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari associate with the “pack,” but certainly more that becoming, multiplicity, contagion than butterfly as metaphor for the journey of an individualized soul.

I suppose the poem downplays metamorphosis, and all its metaphorical associations, compressing the monarch’s ontogeny, from egg to larva or caterpillar molting through its instars eating their own shed skin to pupal stage with its cremaster to chrysalis and finally butterfly, into one stanza, like those time-lapse photography films we all watched in school. Instead, “Unfolder” dilates on the risky moment of sexual encounter.

Maybe ecopoetics doesn’t talk about sex because it’s often so interested in the unsexy business of science. The science of monarch reproduction (ok, I’ve made a leap, from sex to reproduction) certainly occupied my mind as I wrote this poem—just as certainly as I continue to be excited by poetry conceived as an instrument for researching the natural world. This scientific orientation has rarely felt at odds with the activist motivations of ecopoetics, even if decolonial awareness now draws attention to the uneven socio-ecological terrain on which research is situated, a violence that science has been instrumental in imposing as an instrument of empire.

Still, I’ll venture, in the ‘two spirited’ sense that Potawatomi scientist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer has so eloquently expressed (in Braiding Sweetgrass), that natural science is more likely than not to bring us closer to the kinds of attention culturally sustained, in different ways and in relation to different environments, by indigenous peoples around the planet. Can we differentiate scientific curiosity from the mindless desire (whether of consumption or of the narcissistic clicks at the heart of the attention economy) driving our world-ecology to the brink? As the climate crisis heats up, scientists do seem increasingly at odds with the capitalist system they helped create. For “Unfolder,” I didn’t research indigenous knowledges about monarch butterflies, which must be as various as the different territories this species traverses, nor even classical Western lore (further afield, there’s the saying about the Chinese philosopher who dreamed he was a butterfly), but I did read about what naturalists call the species’ life history.

Monarch butterflies’ dependence on milkweed turns out to be a predator deterrence adaptation, as the milkweed makes them bitter. (Ever tasted a monarch?) Enter the viceroy butterfly (Limenitis archippus), whose mimicry of the monarchs’ wing patterns (those brown eyes that add an additional startle for the aspiring predator) hitches a ride on its signaling without a correspondingly bitter bite: “wing deep/ slips between sign & referent.” This imitation turns out to be more than flattery, and less than sincere, when the tastiness of the viceroy encourages predation on monarchs.

Some things about this poem I still don’t, or no longer, understand (some of the last stanza perplexes me, nor can I give reasons for the 13-line, dimeter/ trimeter form), but I know that as I wrote it my thoughts turned to the Old Occitan troubadour poetry I had been studying—a high point of sublimated eros in Western writing—and in particular to the figure of the “lauzengier,” the courtly rival whose flattery often masks slander. Parallels between the formal imitation and variation at the heart of Old Occitan poetry, at the origins of lyric poetry in Western vernacular languages—most likely an importation of complex forms from Mozarabic, Sephardic, Moorish and Berber influences flourishing in music and poetry from Al-Andalus—and those at work in, say, the sexual selection of songbirds, continue to inform my own efforts at “writing the natural world.”

Anthropomorphization? I think not, inasmuch as the emphasis is, if not on structural homologies, on things not being what they seem, on the need to look and listen more closely. Not to get at the essence of the thing, but to become aware of ecological complexity. I have my Rilke moments as much as any poet, but it’s slippage and deception, not immanence or harmony, that draw me to natural phenomena—where poetry and, say, monarch butterflies can meet, in what Jacques Derrida calls the “structure of the trace,” there and not there, meanings slipping into their opposites. As much as advocating on behalf of wild forms of life and the ecosystems they rely on, my poetry seeks to deconstruct the simplistic opposition of humans = bad / nature = good that, in fact, does more to harm than benefit the life it claims to love.

A couple of metaphors the poem indulges in are wing as (stained glass) window, bringing, I suppose, a kind of religious feeling, and monarch butterfly as flame—an end prefigured in the pun embedded in the polypototon of “ardor” in the poem’s first couple of lines. Burning desire: where else does lyric poetry begin? If not with that thin fire racing under Sappho’s skin.

Is it this kind of desire, burning past life-and-death distinctions (failing to note when flattery is sincere and when harmful), that leads us into fire? The fire of phosphates and pesticides burning the weeds and flowering plants our pollinating insects rely on from the very edges of our agro-industrial fields? (One aspect of monarch ecology that “Unfolder” doesn’t get into, and it’s a rich area for connections with poetry, is pollination.) The fire of burning forests? The fire of fossil fuels combusting and supercharging our planet’s atmosphere with heat-trapping gasses. The fire of weaponry raining down on civilians, enforcing the domination and genocide at the heart of our “carbon democracy.” The fire of the sun bringing relentless heat (and drought, storm, flood and fire), not helping if we fail to help ourselves. Is it desire, even the desire of monarchs butterflies, that leads to a planet of cinders?

I wouldn’t be so fatalistic. The question for this poet, I suppose—in a time when the stolidly reliable but ever so unsexy “documentary” services of art and poetry get the lion’s share of environmental credit—is whether lyric poetry can do ecopoetics? Can desire guide science in non-harmful directions (or vice versa)? Is a poetry of sexual desire inherently anthropomorphic? (And does desire have to be sexual?) If not, how can the self-consciousness of our language guide desire toward species being in greater balance with the needs of other life forms? At the more technical, and perhaps trivial, level of craft—at a time when the novel remains the preferred occasion for ecological reflection—can the compression of the lyric poem accommodate ecological information? Are these questions better left to the young to confront and solve?

The poem begins with an ending, or what at the time seemed like an ending, with news of a forest fire at the monarch butterfly sanctuary. Most ecopoetics nowadays begins with apocalyptic news. If I wrote the poem today I’d have to write in relation to not the destruction of an individual grove but of an entire species, with Danaus plexippus on the IUCN redlist of vulnerable species, the population having shrunk by as much as 72% over the past decade. (The western population has declined by an estimated 99.9%, while the eastern population also had shrunk by 84% between 1996 and 2014.) I might be tempted by analogies between the migratory life of the subspecies and the migration of so many humans on the move, displaced by war, rapacious extraction, and the catastrophic effects of climate change.

So it may be that the initial motivation for the poem is not desire but grief, if not fear. How is it that I managed to turn the poem back toward a time, so innocent (it seems) of the kinds of bad Anthropocene feelings that now consume us, when most of us were not even aware of such phenomena as greenhouse gasses or climate change?

On my way down from my private moment in the sanctuary amidst copulating butterflies, I caught a ride on the back of a logging truck, feeling a bit too shy to speak with the men who had reached down to help me onto the flatbed where some freshly cut and skinned tree trunks lay strapped. We shared smiles as the truck bounced on down the rutted road. The presence of logging on that mountain did make me wonder, though it turns out the threat to the butterflies comes as much from north of the border as from south of it. The monarch sanctuary is now part of a protected UNESCO World Heritage site biosphere reserve (and the IUCN recently downgraded their Danaus plexippus listing from endangered to vulnerable). What I experienced there only found an outlet more than a decade later on reading that newspaper article. It may be that grief, fear, desire, joy all connect to some deeper current of feeling (or affect, the philosophers might say) that is more than human.

Whether or not “Unfolder” is a successful poem, lyric or ecopoetic or otherwise, I like that it risks attempting those deeper connections. I still read the poem to audiences as one, albeit small, contribution to advocacy on behalf of the threatened monarch butterfly.