Life in Public

Test

“Explore What Sparks Poetry” is made possible with funding from The Virginia Commission for the Arts.

When I think of my own hearing loss, I think of irreparability, a loss that runs only one way, converting my skull to a locked vault, a cave. I like to be alone there, to study how it susurrates. Sonority, that tideline's arrival, retreat. Other losses are more acute, and I bear them bitterly. Like the constellations in the dark night of Greek thinking, the night sky overwritten with predators and prey. Washed with milk, they sink away to hide behind the sun.

Catch Up on Issues of What Sparks Poetry

We are left instead with anti-image. With possibility of/some great coiled energy. Anti-image, ironically, makes real the possibility, and possibility the real.

Tell all the truth but tell it slant—. The moment I begin saying to myself Emily Dickinson’s first line, my tongue flicks rapidly to the roof of my mouth for the first sound in the first word “Tell.” The same exact little movement happens at the end of the line’s last word, “slant.” In this pre-industrial, bodily way the reader becomes the poet’s instrument. In a way, it is as though they were one. But in another way, the bodily nature of the line enacts the double solitude: the reader’s body absolutely itself, utterly separate from the equally solitary poet who made the line: solitaria. Ferry’s poem is about the empathic loneliness Johnson’s prose suggests but cannot embody.

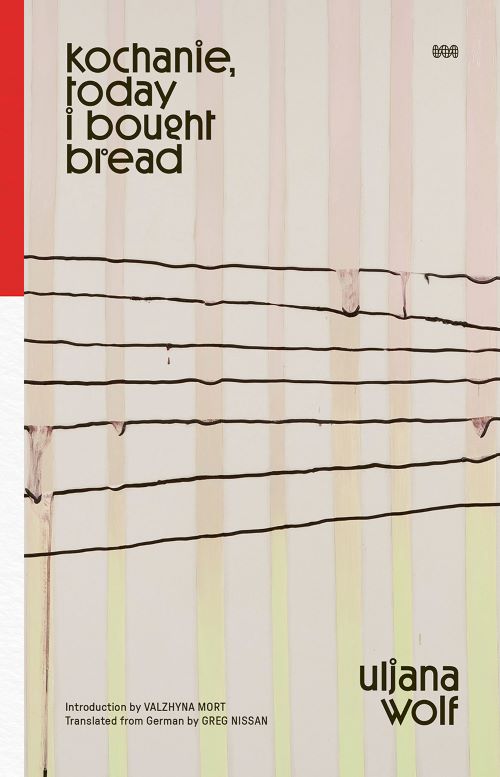

Translations are acts of mimetic excess, they generate too-much-ness, volatility, transformation.

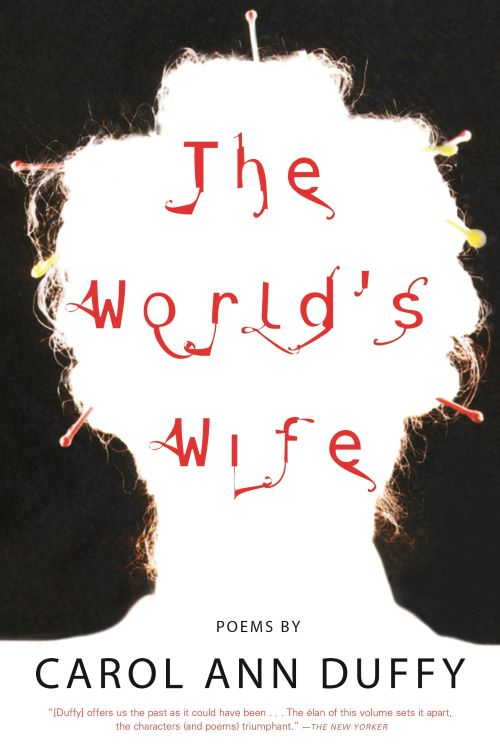

This approach—Duffy's dual reverence for the Western Canon and her simultaneous roasting of it (for all those it omits)—has stayed with me in a profound way since that morning in Long Beach so long ago, and not just in books but in other facets of life. Even now, when I walk through an art museum, say, I will imagine the essential figures who aren't there, who never made it onto the canvas, who, to crib a line from Duffy, were disinherited out of their time.

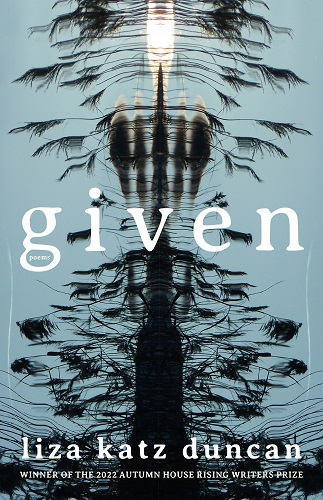

Each of us enters Johnson’s book through that singular, seemingly never settled and always unsettling noun, holding a small flat object labeled Inheritance. A thing made and possessed by another, and now — is it really yours? A thing given, but was it freely chosen?

The way a poet turns their life into an artifact, paginated evidence of having lived… one of the key masterstrokes of this poem is that its form enacts the realities of its making, of the position that the poet, over and over, finds themselves in: that one must constantly unearth one’s life if one wants to keep it whole. The present falls onto the poet’s past like shovelfuls of dirt. If you want to take life with you where you’re going, you have to dig it out yourself.

What would happen if a poem “talked” to its reader? What would the “voice” of this poem sound like?

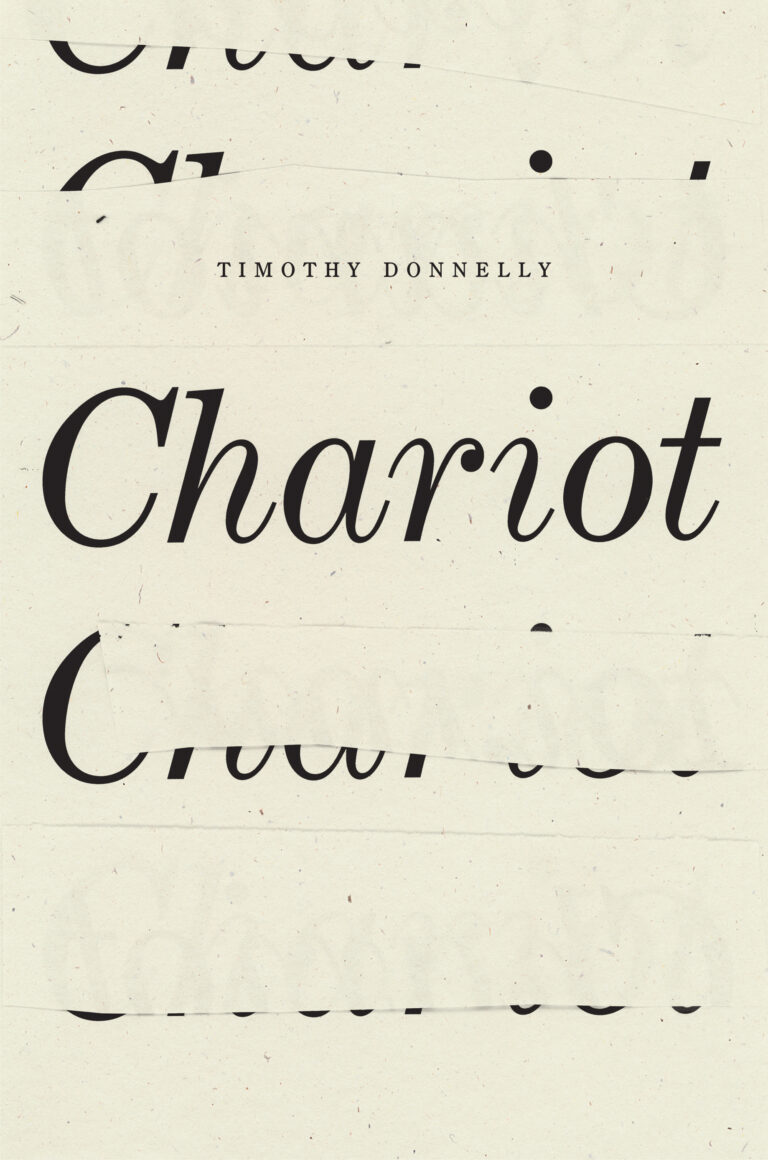

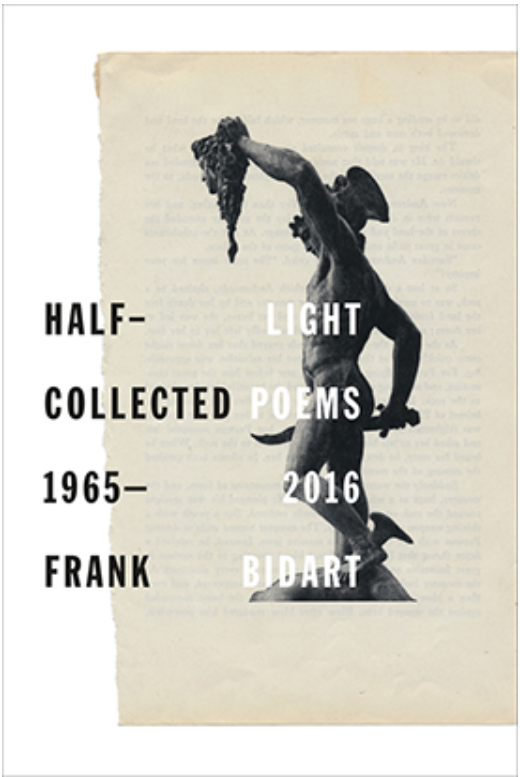

This vision of desire—to become the thing we love, to be remade in its image, to gradually take on its form—is the site of this poem, the mercurial “thing-that-is-struggling-into-existence” at its heart. In a 2015 article whose title contains its plea, its manifesto and its thesis—WE FILL PRE-EXISTING FORMS AND WHEN WE FILL THEM WE CHANGE THEM AND ARE CHANGED—Bidart describes the process of writing poetry in terms of being “gripped by something that struggle[s] to find existence through the medium of language, but whose source [is] not language”.

I love a poem that is about everything. Bhanu Kapil’s tender “Seven Poems for Seven Flowers and Love in All Its Forms” is this way, both about flowers and about not flowers, expansive and contracting in its scope.

Repetition often has an incantatory effect. Nursery rhymes use repetition, rhythm, and rhyme to grant the wish laid upon the first star. Despite this magical aura of naming and claiming, wishing evokes passivity. Wishes are childhood's epistemological firmament, they are part of the structures of intimacy available to children in a world controlled and administered by adults.

All this time, the vow held me and asked me to return to it with answers; “you” had become “I,” and “again” and “more” implied I’d been here before. What was I asking myself for? The rest of the poem? Myself? I’d hoped to depict an answer in passing material. But the wish itself was the world.

Whether or not “Unfolder” is a successful poem, lyric or ecopoetic or otherwise, I like that it risks attempting those deeper connections. I still read the poem to audiences as one, albeit small, contribution to advocacy on behalf of the threatened monarch butterfly.

I have patched together a poetics of Black persona. That is, a poetics that sees the object—inanimate in all the ways that make it “nonhuman”—as a thing that can, and does, speak. This is how, I submit, we can speak to the land, and (more importantly) listen as it speaks back.

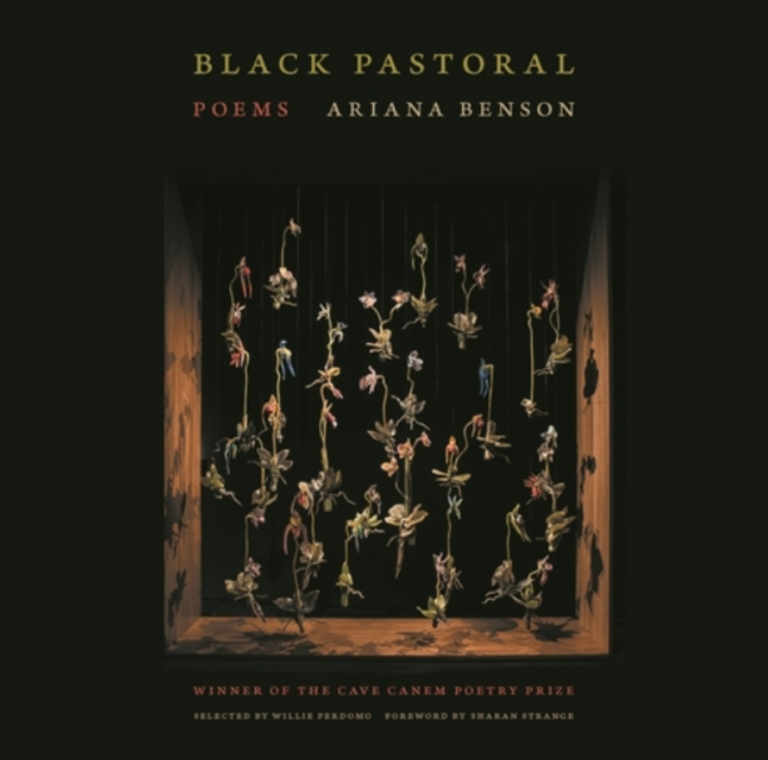

![Cover of Harpy Hybrid Review [Winter 2021]](https://training.poems.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Tierney.Orchid.cover_.jpg)

Michael Marder’s claim that “‘Plant-thinking’ refers to…the non-cognitive, non-ideational, and non-imagistic mode of thinking proper to plants (hence, what I call ‘thinking without the head’)” is an intriguing proposition that underlies my misadventures into future plant life—including artificial flowers—that I am calling a field guide to future flora. this series on biofutures meditates on what plants might emerge in our post-climate-changed worlds, what expressions of vegetal intelligence, wit, and desire might take root amidst the socio-political decompositions. I don’t imagine this future as utopian but more optimistically punk. and what is more punk than plants? what is more optimistic than poems that think without a head?

“The Uncles” are not actual people but attempts to personalize the tragedy of Superstorm Sandy through memories, anecdotes I had heard from neighbors and read in the news, bits of conversation, and places and images that continue to haunt me to this day. I chose the sestina’s six ending words to drive home exactly what was being lost, and what we continue to lose, both concrete (bay, fence, birds) and abstract (home, ways of knowing). I wanted the reader to experience the same constant presences, the places and events that had become a part of my daily life, over and over again.