BOBCATS AND CITIES: FIFTEEN YEARS OF TEACHING POETRY INSIDE AMERICA’S PRISONS

This morning a bobcat walked by my kitchen window as I washed dishes. I live in Los Angeles, or a suburb of, one of these tiny towns that blossomed out of Route 66, nestled up against the San Gabriel Mountains. It’s not unusual for us to get wildlife – we recently installed bear locks on our trash cans – but every time we do get a visitor, we’re stunned. I’m caught watching this beautiful, majestic thing traipsing across asphalt. This thing that I don’t understand, can’t possibly wrap my mind around. Steve Winter’s photograph of P-22, the mountain lion the city recently mourned, up against the Hollywood sign illustrates the competing realities of nature and city. With my mind, I understand that Los Angeles is one of the most biodiverse cities in the world, that it grows out of the hills and spreads into the ocean, but, with my heart, I can’t help but wonder, how does this beautiful thing exist here.

I’ve taught inside prisons since 2008. When someone asks what teaching inside is like, I tell them a classroom is a classroom is a classroom. The literature on higher education in prison pedagogy stresses this – the instructor’s job to create the university in the prison, as much as that’s possible. Erin Castro’s work is a good place to start if you’re interested. I do do this, as much as I can, and it’s an important teaching philosophy to maintain, but it’s still just that – a philosophy. Of course, the classroom is a classroom, but a prison is not a college campus. A prison is a prison is a prison.

Prisons are designed to punish, and one of the many, many ways they accomplish this is through isolation. The system is constantly creating barriers to connection. To paraphrase Angela Davis, prisons disappear people, and they do that by separation. We hide prisons in remote places. Out of sight, out of mind. I co-direct a prison education organization that hosts a systems-impacted writers’ contest and sponsors an editing network for incarcerated writers. Our day-to-day has us corresponding with incarcerated writers across the country via predatory pay-per-character email systems and the postal system. Our letters are regularly returned because someone has moved dorms or is out to court the day the piece of mail was received. Florida has banned our editing network entirely, because an administrator believes giving incarcerated people feedback on their writing is a ‘business opportunity.’ As a university organization, we have the time and money, the patience and privilege, to track someone down through byzantine 90s-tech databases. We have a team of faculty members and thoughtful graduate and undergraduate students to ensure that we keep connection to this one person. Imagine, however, a son, pressed for time and money, trying to reconnect with his incarcerated father. We know that people do better while incarcerated and upon release when they have strong ties to family and community. Despite knowing this, the state’s prejudice to punish, to hurt, prevails.

One of the ways I teach college writing on my university’s campus is by not teaching writing. My classes talk about the world, our place within it. What we did over the weekend. How Avatar sucked. This is harder inside. Most prison systems have rules regarding ‘overfamiliarity.’ I can’t tell my students in prison what part of town I live in. What my wife’s name is. Where I grew up. That my father died five years ago and I remember him every day, his quick wit and kindness. That the way he told stories made me the writer I am. The fear is that I will develop a relationship with the person I am teaching, and that relationship will make me susceptible to manipulation or extortion. The prison mandates that we remove the human from the humanities. And what is poetry if not personal? Policy versus practice. I still share myself with students. I can’t not. A classroom is a classroom – and after 15 years of teaching inside in Alabama, Louisiana, and now California, a student has never asked me for anything.

After I finished up drying plates, I checked Instagram and saw a former high school student of mine, now in her late 20s, is publishing a book. I sent her $13 dollars. She was ecstatic, said that her creative writing journey began in my class. My wife and I, just the day before, experienced a devastating personal loss. And the appearance of this cat and this news lessen the blow. I remind myself there is magic in the everyday. I have never been able to maintain a connection to my students in prisons beyond the confines of the semester. The prison prevents this.

On the first day of class, sometimes, students in my prison classes don’t know why they are there. They’ve just been transported from one portion of the facility to another, told to move without reason. My presence and that it’s a poetry class – all a surprise. Days inside prisons are strictly regimented until they’re not. The prison creates expectations and then as soon as they’ve become normalized, those expectations are subverted, putting people in a constant state of terror and anxiety. This is another way prisons punish – chaos. Yet another way they punish is by stripping people of their agency. Folk no longer get to choose what they’re doing or where they’re going. And sure, I’ll give it to you, the argument could be made that this is what someone loses because of his conviction, his ability to choose.

What it also creates, however, is a hostile teaching environment. Data show that most people who are incarcerated will reoffend upon release, about two-thirds. Data also show that as soon as someone steps into a classroom that metric flips, and for every further educational milestone achieved, recidivism decreases. Students with BAs from programs like Bard’s or Pitzer’s have something like a 3% reoffense rate, compared to the 70% of the general population. Outside the scope of this conversation but important to mention is that 3% reoffense rate is usually the result of drug dependency, which illustrates another failure of incarceration. We know that education is the cheapest and most efficient way to effect decarceration. The prison knows this, but instead, it chooses to inflict harm upon those who are seeking education and those who choose to provide it. As soon as I step into the classroom, the classroom has already failed my students.

And this goes beyond merely my classroom – all classrooms have failed these students. Around 70% of people come into prison without high school diplomas. Students have been chewed up, spat out, turned over and over, ground down, all these terrible metaphors for consumed and reduced, by education. Despite being ‘cool’ in my 20s, maybe into my early 30s (maybe? maybe…), tattooed, in t-shirt, wearing Dunks, now in my 40s, I’m gray, bespectacled, and wear a bad moustache. I walk into that room and look like the worst kind of English teacher. I am a representative of the prison. How do I create community with a population that is suspect of my whiteness and authority?

I try by giving students autonomy in the classroom, by returning agency for those two hours. The first exercise we do is the history of our names. Students freewrite about why they’re called what they’re called, and we read those. One tells an incredible tale of a childhood nickname gone wrong that he can’t get away from now, even now in his late sixties. A grandparent the family wanted to honor. How Mary was the name of the nurse who delivered her. How he always hated being called Clarence, but the other option was worse, Dookie. The exercise also creates opportunities for trans-students who are often housed in facilities contra to their gender identities to name themselves. Students wrest a bit of themselves back from the state. They are no longer a deadname or number or an inmate, but instead, a person with history. From the exercise, we’re also able to shift from a traditional instructional environment – the one that most of them are familiar with – where I tell them things and they repeat them back. Instead, the classroom becomes a site where their stories and lived experience are worthy of deep consideration.

We talk about what poets do and how they name. I introduce Joyelle McSweeney’s idea of hyperdiction, that each poet has available to her a completely unique vocabulary, and thus voice, created from and by the communities she’s a member of, her life experiences. When I start the discussion and say the word, hyperdiction, students often express trepidation – they mistake hyperdiction for grandiloquence. They think they must write in capital-P poetry, whatever that means. This hearkens back to the classroom as a place of trauma, a place where the student is incapable of doing anything right. But then I talk about my teen language of cars – cherry picking a big block 396 from a 71 Impala. We’d put it on cheater slicks and skinnies to run better straight-line times stoplight to stoplight. There’s beauty, I say, in culture, a culture that perhaps is not usually associated with capital P-poetry, whatever that means. We get to make hot-rodding poetry.

Further borrowing from McSweeney, I ask students to define a community they’re members of and to list all the language that’s particular to that community and then write litanies, long poetic lists. Students often draw from previous lives. Jobs. Or from the prison itself. The prison then becomes an object of study, the student’s place within it, and through this study, the prison is a site for critique. This is not to say that students aren’t already critiquing prison; it’s that now that critique has value in this space, the classroom. Just in that first day, I’ve earned trust by allowing my students to talk about what they know and to demonstrate their expertise. I try to use the classroom to return something, anything, just by giving them the keys.

The next major assignment is a prose poem. On a practical, pedagogical level, again, my students often have a lot of anxiety around language, or more specifically, its correctness. By taking lineation out of the assignment, students can focus on sound, music, and play. There’s one less plate to spin. We read a bunch of examples, talk about the form as a place to express dualities. Contradiction. To make the banal magical. What is it? Poem? Prose block? Who the fuck knows? Actually, it’s whatever they want it to be. By calling it a poem, suddenly it becomes a poem. What power there. What power to be able to name something and it just then be that thing, regardless of what anyone else says. The classroom is a classroom, but there is a prison outside that door. The prison disappears because we say it does, just for a moment.

In classes, students don’t take material, they take teachers. That is, my prison poetry classes are not poetry classes, but my class. Or at least they start that way. I came to poetry through story and prose, and that’s why we begin there – so I can offer myself. I tell them my father had thirty different ways to tell me how ugly I was: if ugly were a stop sign my face would be all over town; I looked like I got in a hatchet fight and forgot my hatchet; I fell off the ugly tree and hit every branch on my way down; I looked like death on the corner eating Lifesavers…The list goes on. And each way was a way for him to tell me that he loved me. It was through that duality – the expression of one thing meaning another – that I came to poetry.

I dropped out of high school, was dyslexic. School was hard. I didn’t make sense within it. But I found books. And I realized as I grew up and my study of poetry deepened that poems were controllable systems. Little, perfectly engineered machines. Engines. And that poets were gods of these machines. I came to poetry at a time in my life where I was out of control and felt powerless, and that poetry was a place, the only place, where I had control. I try to give my students that. Today, I live with chronic illness, and some days, I can’t get out of bed. Or I see a doctor and have some new, terrible diagnosis – most recently, pulmonary hypertension, in addition to my failing heart, lung disease, and lupus. But a poem, man. Through it I escape the body. I can open a document and push around a comma for hours. In so many ways, a poem is the only place I have control.

And after those first two assignments, I let the class dictate the rest of the material. Organic discussions around interests lead us. In one class, students very early on started writing in Spanish and English, moving between the two seamlessly; fuck it if the reader didn’t speak Spanish, one writer said. The reader doesn’t matter, or at least is secondary to the writer’s experience. For the rest of the semester, we read writers who do the same. In another, we talked about ekphrasis, the Black arts movement, protest poetry of the sixties. And then that’s what we read, what we wrote. The class starts as my class, but then it becomes the students.

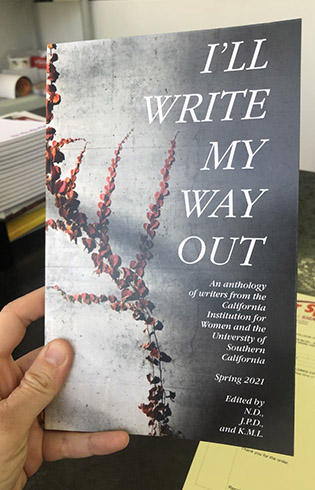

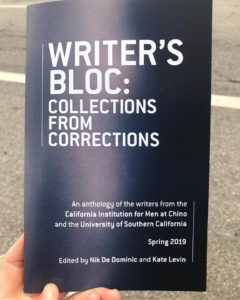

For each of these classes, I produce a printed anthology of our writing. I write an introduction, the book comes with a table of contents, is filled with students’ writing, and ends with their bios. It’s a real thing and my students, now published authors on a university press. Although I will never see them again, I get to give them with this.

I recently heard Ross Gay on NPR talking about his book, Inciting Joy: Essays. He said something like the intolerable provokes joy and that joy is the result of connection. It’s not hard to read joy, here, as a form of creation or art – that the intolerable provokes art and art is the result, or attempt to, make connection. In “Etiology,” Elaine Kahn writes, “Cruelty made me. Cruelty and the sweet smelling earth…” Yes, this. Sometimes when people ask me what it’s like teaching inside and I tell those people that a classroom is a classroom is a classroom, they follow up, ‘yeah, but are they any good?’ I get incredulous. Angry. I ask, why wouldn’t they be? Anywhere there are people beautiful art is being made. Why not prison? Poetry perhaps makes some of its most sense in prison – because people through poetry can take back at least a little bit of what’s been taken from them. But I understand the question, where it comes from. Poetry in prison is a bobcat traipsing across asphalt. When we build homes against nature, nature doesn’t go away. And when we cage people, despite the state’s best effort, people do not become anything less than people. Art doesn’t go away. I know I live in the city, but I know what came before the city, that it somehow still thrives here despite our best efforts to destroy it.