I have always wanted a daughter. I have always wanted to know all of my mothers and foremothers. But I don’t know if I can say with certainty that I have always wanted to be a mother. Even writing this, I falter—can one want a daughter but not want to be a mother? Can one desire daylight but spurn the sun?

To be—to exist (as someone), to have the characteristics of something.

To embody, perhaps, or to occupy a particular stance, or situation, or identity. I step into my name, I inhabit my body. I am, I am—what? If I am anything, it is unsettled, irresolute. Of two minds.

“Matrilineage [Umbilicus]” sprung from this unsettledness, not halfway into my first pregnancy, when my body ceased to be entirely mine. I came to the page eyes closed, hands outstretched to trace the contours of my thinking. I could not yet trace the face of my child, so I tried instead to touch each thought as it was born.

A thought: There is new breath budding under my breathing.

A thought: Another life is attached to—depends on—mine but I can’t see it.

A thought: Can I bear this? Who can bear this?

A linea nigra was by then faintly visible on my stomach, beginning at my navel. Daily my body changed and outwardly divulged its labor. I began writing “Matrilineage” with the linea nigra in mind—a line, a rift, a thread, a cord.

Motherhood is fraught with failure, beginning with the knowledge of pregnancy. Each day passed slowly and terribly, convinced as I was that I could miscarry at any moment. Twice, three times a day I would Google the probability of loss. I felt no joy, no anticipation. Fear precluded even the possibility of wonder.

All my life, I have feared failure, feared the penetrating sting of disappointment. To distract myself, I turned my attention to my foremothers as examples. I began with Eve—the first mother in the matriline, though motherless herself. Eve, whose name connotes before. Whose name heralds her fate. The onus of being the first mother is unimaginable. What origin is the unimaginable?

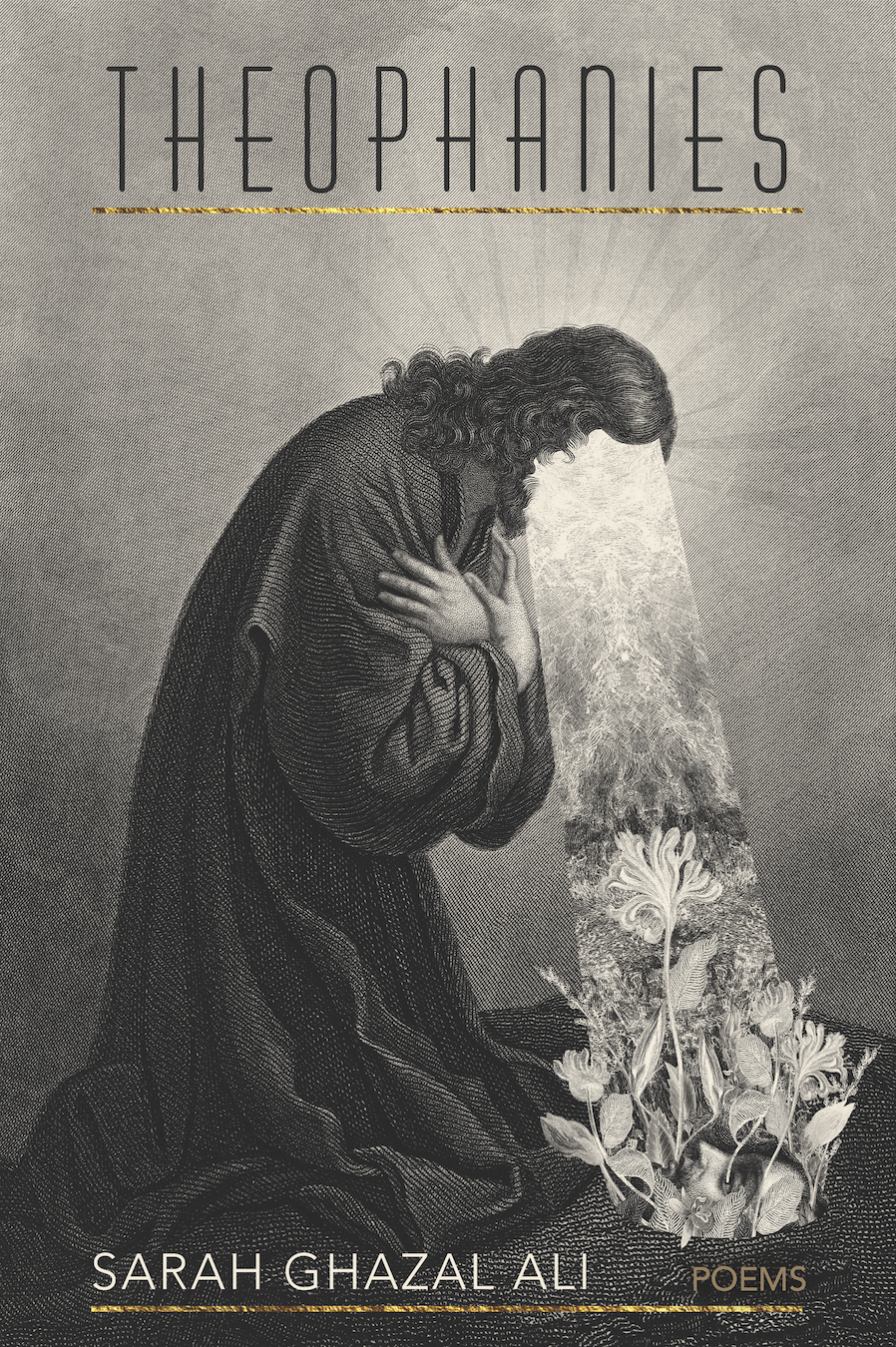

I lost interest then in my singular voice, uncertain and afraid. Persona offered a trail into others ways of knowing and speaking. Persona offered a path through the unimaginable. Throughout my first book, Theophanies, I wield persona to trace a foremother’s face in the dark—Sarah, Hajar, Eve, Maryam. I cannot know them, but in the absence of definitive knowledge, I can speculate. Through speculation, through the assumption of another’s voice, I can clarify my own. Using Sarah-as-foremother as a mouthpiece doesn’t reveal anything true about her. Rather, it illuminates my own inclinations, biases, and assumptions, long-obscured and buried. However frightening, however troubling. By braiding together multiple voices in a contrapuntal, I can better locate my own. I’m not sure how many women are speaking in “Matrilineage [Umbilicus];” I consider it a choir. On either side of the linea nigra, women speaking, singing, and bearing witness.

It was crucial that the poem could hold the precarity I carried in my body. It can be read multiple ways, full of truths and mistruths. The contrapuntal is an apt form for ambivalence. I didn’t have to know—I just had to speak.

In “Matrilineage [Umbilicus]” I become—begin to be. Between the mothers that came, and those that will—now, here, I am.