Public poetry is an idea I’ve always found challenging. I believe poetry does important work and that that work has a bearing on real life, but I’ve often been stymied by the question of how poems can effect material change in a world that is, generally, not especially interested in what poetry or poets have to say. Part of what I believe makes poetry poetry is also what makes poetry allergic to the banalities and compromises required by true political engagement. That said, I never cease to be annoyed by a certain kind of aestheticism that throws Auden’s “poetry makes nothing happen” at any insinuation of poetry’s practical relevance. Not least of all, this chafes because it utterly misses Auden’s point. Duh, Auden loves irony… But, this little essay isn’t really about Auden.

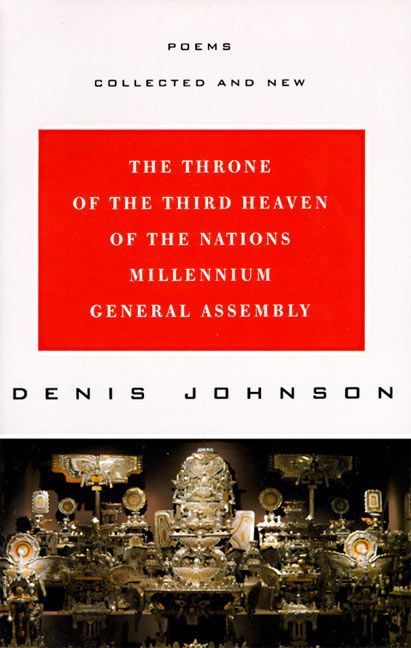

James Hampton, as the epigraph/epitaph to Denis Johnson’s “The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly” informs us, was a custodian for the General Services Administration of the federal government. He was also a visionary artist of the naive, art brut, folk art sort — self-trained, unknown and uncelebrated in his lifetime, a true mystic, whose artistic goals appear to have been mainly sacred goals. So, in many ways Hampton was the opposite of W. B. Yeats, in whose memorial poem Auden’s famous phrase was first delivered, and whose interest in mysticism and mythos were generally subordinate to his investment in an Irish national-cultural ideal. Hampton was also, as Johnson’s speaker observes, “probably insane.” This aspect of who he was is not presented as any sort of qualification of his accomplishment or of him as a person. It is part of the story, part of what little we know about his biography. It is also part of the speaker’s story and the reader’s: “If you stand in the world / you’ll go out of your mind. / But it’s all right.”

“The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly” is a public poem in a number of ways, even if it doesn’t make any grand (or correct) statements about our immediate political situation or about anything that very many people really know or care about. It is a poem about a private figure who became a public one only after his death and only by chance. A poem about a work of monumental public art and about trying to make sense of it. A poem about race and religion. But, none of these elements in the poem strikes me as the core point. If I had to say, and I’ve structured this so that I guess I do, I’d say the point of the poem is that “poetry does make something happen.” I’m taking some liberty with the term “poetry,” of course, but anyone who has seen the Throne at the Smithsonian knows it is as close to poetry as it is to any other genre of art. Poetry, all great art, has the potential to change what and how another person sees.

Johnson’s poem is an account of the happening that poetry can make happen, the inner transformation (“I was his friend / as I looked”). The mysterious process by which art is created and transmitted turns into real intimacy between two people who never met (and for whom befriending people in daily life may have been tough). Hampton is forgotten in his hometown of Elloree, South Carolina (“Nobody … in all of Elloree … knows / his name”). But, for Johnson’s speaker, Hampton the “deeply abysmal” is also the “deeply blessed,” and his creation, his “revelation” has transformative powers. With a plain, understated gravity, the speaker describes something very rare: “I’m glad the Throne exists: / My days are better for it / and I feel / Something that makes me know my life is real.” Auden says of Yeats, “He became his admirers… modified in the guts of the living,” as a way of describing the haunting echo of Yeats’s work persisting in those who (like Auden) have already read it and also in those who will come along to read it after. Johnson’s poem is an account of that process’s phenomenology, what it feels like to undergo.

And that brings us to ourselves, readers of poems by poets about poems by poets, which is a discourse, which is all we have to connect us in this world. If I hadn’t read Denis Johnson, I would never have known about James Hampton. I likely never would have gone to see his Throne at the Smithsonian over-and-over. Nor again-and-again read the inscription perched at its top (“FEAR NOT”), and however briefly put away my fear. All art, poetry, language is relational: signifying only through brief connections that mainly occur by chance. People—small and miraculous prisoners of our independent bodies—are relational, as well. Public is where new relations temporarily emerge. The process is very hard to mimic, but when it happens, when poetry makes it happen, our days are better for it, we know our life is real.