I found books intimidating as a kid. All books. The words inside them, of course. Poetic words were especially daunting. But I do remember being impressed at some point by the poems my peers published in the school literary magazine—impressed less by the poems themselves than by the fact that people my age (13?) believed they could write poems. Noticing that feeling must have primed me in some way to consider the possibility of writing poems for myself. In some ways, I think I wrote my first few poems or lines of poetry just as an adolescent experiment in identity. I didn’t really have any frame of reference for what poems were, but I knew that some people thought they had value. Did I think so? And if I did, could I find a preferable self there in Poetry? The answer continued to be “no” for some time, as my early exposure in the classroom to “real” poems confirmed suspicions that literary language was not about any life I could smell, taste, or otherwise imagine and therefore must not be about me. I slowly came around to Shakespeare and to some novels, but all verse felt kind of like what Alexander Pope still feels like: elevated for unfathomable reasons, filled with rhymes like “clos’d / compos’d” and “adorn’d / mourn’d.”

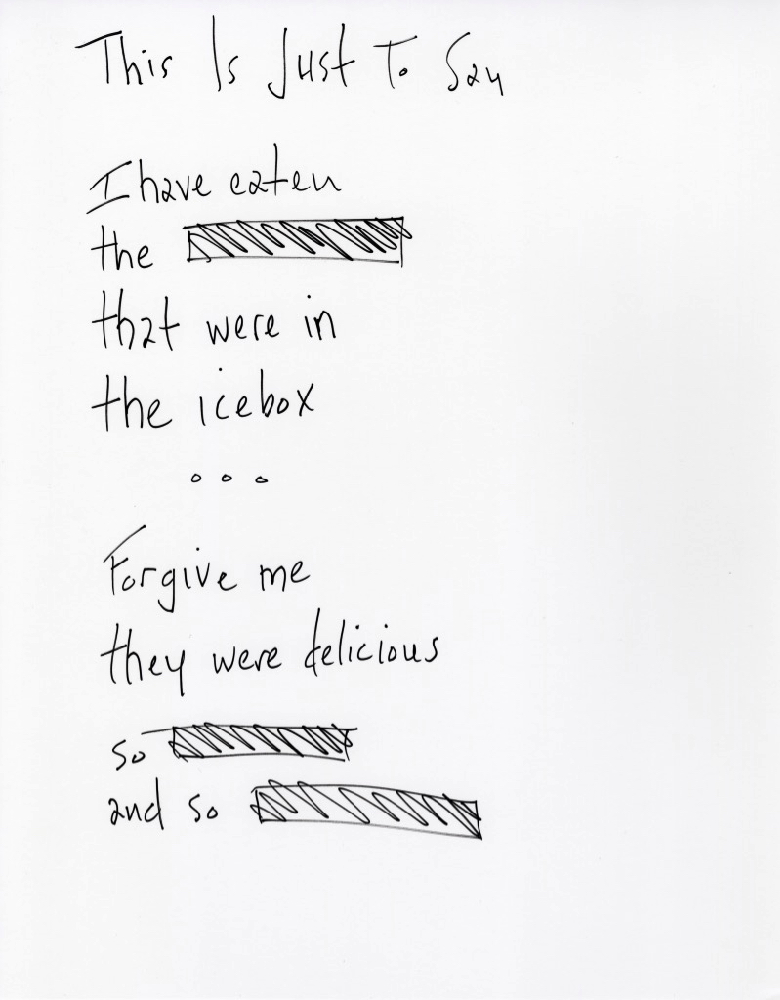

I persisted in writing poems, nevertheless, for reasons I can’t quite articulate now, but I don’t think I really felt “permission” or saw a true point of egress until I read William Carlos Williams’s “This is Just to Say,” and I still remember that moment vividly. My English teacher told the class to flip through the Norton Anthology and find a poem that we liked. Then, he went around the room and had us explain what we thought the poem was about and why we liked it. Typically, I would have hated that sort of task, but I stumbled on the poem as if I’d stumbled into Williams’s actual kitchen. The poem’s mundanity seemed all wrong to my notion of literary propriety, but in that mild transgression—in the context of this poem that I found curiously moving—I could feel those faulty notions getting annulled. At the time, I was impressed by the spareness of the language, what I took to be the naturalness of the voice, and the documentary feeling of calling a refrigerator note a poem. But more than any of that, I was haunted by something being transacted in the poem that was harder to describe. Now, I think I’d call it the melancholy tone and the work that tone is doing to communicate something about love, absence, connection, and isolation. The poem is ultimately more about what isn’t there (the plums, the speaker, respect for the beloved’s property) than it is about what was there momentarily (the sensual pleasure of something “so sweet / and so cold” or the speaker’s remorse, however genuine). All that is really left is a way of speaking about what is passing and what has passed, about the limits of our ability to share the world even with those we love the most, dashed off with a perfunctory “just.”

How much of this—the very subtle irony of the poem’s humility, for example—was available to me in that first reading is hard to account for, but basically, I’ve never stopped thinking about this poem and the depth of the feelings and questions it prompted in me—the little vision it opened up for me. The poem gave me permission to look at poetry as an instrument for touching elements of life that I intuitively knew were there (or palpably missing) between the details of commonplace experience and just below the phenomenal clamor—a lease I’m still exploring.