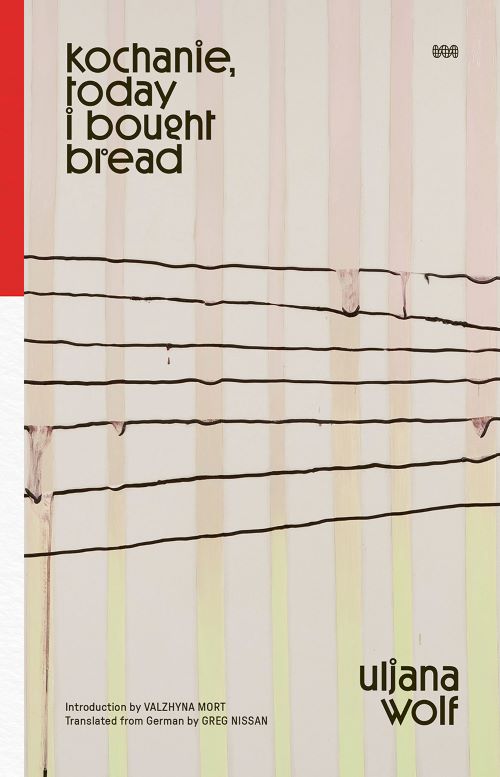

Lyric Serialism in Uljana Wolf

I’m haunted by the way sound unravels as a melody falls apart.

When my daughter’s favorite music box begins to slow down, she says it is time to rewind it. For her, the slowing corresponds to an action that must be undertaken to start the music again. For me, it reveals the limitations of the medium. Slowing down sound tends to lower the pitch slightly, accounting for some of the eeriness. But the music box is condemned to play the same song ad infinitum, with little variation (unless one includes the slight discrepancies in the eerie slowing-down sound). The music box reveals itself to be a machine rather than a lyre.

*

Uljana Wolf’s “my cadastre” was published as “mein flurbuch” in German. In Greg Nissan’s exquisite translation, the poem keeps its original structure, divided into 8 numerated sections, with each section composed of 8 lines or less. The title announces a relationship to property and time: “my” claims ownership while “cadastre” denotes an official register of the quantity, value, and ownership of real estate used in apportioning taxes.

Each section begins with a two-word line: a “my” followed by a plural noun (fathers, mouths, or daughters), where “my” shifts between uses as a determiner, an adjective, and a possessive pronoun. The noun is always plural. The fathers are those “simple men” who “have daughters.” Wolf gathers the daughters together in the “darkest woods” with a plural pronoun reminiscent of Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina.

Across every stanza, the daughters exist in relation to the words of the fathers, for it is the fathers who determine the law, and who act as surveyors of property and inheritance. The fathers decide the boundary that “links / the countries to figures”, and they do this through language. The daughters are built inside the walls of the fathers’ words (and national language), as determined by those borders. The control of language and policing of linguistic boundaries is central to the purity-driven aesthetics of ethno-state ideology. Treason is a trespass of this border, a disobeying of the words of the father. Wolf’s blurring of the two sharpens the way power is asserted in language.

Although first-person pronouns assert their power to name and claim perception, in “my cadastre,” the lonely, uncapitalized ‘i’ echoes the self’s abolishment. Like Bachmann’s nameless choral voices in Malina, Wolf’s are bound by nouns and laws, administered by images poured next to each other to the point of complete saturation. The sparse connective tissue creates a sense of fatedness: one suffocates in that we. No my is inoculated from his power.

*

At first glance, Wolf’s poem appears to be a lyric sequence, or a series of lyric numerated sections that form a whole. But sequencing foregrounds chronological order: choosing how to arrange the parts in order to develop a picture. A lyric sequence like Wallace Stevens’ “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” introduces a figure (often, the subject) and then presents it to us across time. The subject is developed and revealed from different perspectives until the final section of the sequence takes leave of the reader with a particular image. After fiddling to determine which section would provide the most salient final image, Stevens leaves us with the “cedar-limbs” and the ongoing snow. Stevens knew that the last word in an argument sticks to the mind and remains the most memorable.

*

Maybe there is a little machine in this? In music, a serial pattern is one that repeats over and over for a significant stretch of a composition. As a compositional technique, serialism gained prominence in a European landscape ravaged by world wars. For some composers, it served as a response to industrialized warfare and the rise of militarized ethno-states. Serialism mechanizes possibility: it limits what can be imagined or created.

One suspects that “my cadastre” borrows the formal structure of lyric sequence in order to ruin it. In this shattering, “my cadastre” feels closer to something like lyric serialism, a numerated poem that making of the same words and sounds repeatedly without creating a sequence, emphasizing instead the mechanistic ordering of chance. Recombination without closure. Series without sequence. Time with no sense of an ending. A conceptual undertone that asks us to read not for the feel but for the hollowing of what can be felt.

Each of Wolf’s sections rattles the same words and images; there are no subsidiary titles to frame the reading. While numeration provides a sense of chronological order, the material refuses temporal motion; nothing changes or develops along an arc. There is no after. There is barely a before. We don’t receive the satisfaction of a melodic line, or a fugue that provides a sort of resolution through repetition. At moments, it feels mechanical, almost inhuman, driven by a cursed repetition of sharp consonants. Internal rhymes and end-rhymes combine with clipped syntax to mechanize the tone and make the sound inescapable. The speaker is doomed by the form: the limited options imposed by the grammatical structure, the constrained lexicon of repetition, and absence of melodic resolution.

Repetition often has an incantatory effect. Nursery rhymes use repetition, rhythm, and rhyme to grant the wish laid upon the first star. Despite this magical aura of naming and claiming, wishing evokes passivity. Wishes are childhood’s epistemological firmament, they are part of the structures of intimacy available to children in a world controlled and administered by adults.

Before returning to the forest, Wolf gives us a voice in a bracket: “(but it was time)”. The note is eerie: it opens back up onto itself. I hear the music box slowing, leaking that freakish unscrewing like doll-eyes in a horror film.