In local news, a few weeks ago, an 18-year-old woman was set on fire. Althea Bernstein was driving home, and a car pulled up next to her. She said there were four men, that they looked like “frat boys.” Two of them were wearing “floral shirts” and two were wearing all black. They were masked. She didn’t notice them at first, and then someone directed a racial slur at her, and then she felt a spray of liquid on the left side of her face, then someone tossed a lighter through her window. She suffered second and third degree burns on her face and neck.

The world feels unbearable. I’m not sure what’s on the other side of rage, but I know this feeling is unsustainable. I can’t watch TV, I can’t read the news, I can barely scan social media without slipping deeper into a depression. I know there isn’t anything unique about the cruelty we’re witnessing, or the string of events that sparked Black Lives Matter protests across the country. Maybe I’ve changed, or I’m just tired, but I can’t shake my disappointment that our oldest demons, racism, sexism and classism, continue to tear at the fabric of our national identity.

This pandemic has forced us to contemplate our mortality. We’ve become acutely aware of our vulnerabilities. Since we’re facing an unknown future, when I’m not panicking or binge-eating ice cream, I suffer from fits of nostalgia. I was walking past my neighbors’ BLM signs, thinking about what makes a life a life. So much is invested in our individual stories, our accomplishments, the places we’ve travelled, people we’ve loved and lost. The older I get, the more I cling desperately to the past. My home is populated with little trinkets, what people call “tchotchkes.” Our ephemera. Keychains and paper weights, a compass, a stone, a seashell, an old pocket watch, items I believe if I hold them long enough, test their weight, rub them, I can call back the memories buried, that I can hear my grandfather’s voice again or smell the Pacific Ocean, I can remember the sunlight in Italy, or how it felt to be 18.

I’m not that old, but I’ve lived long enough to know that the lion’s share of my life is behind me. I know there are relationships I can’t hold on to, and places I can’t return to. I’m just beginning to see “real time,” the arc of almost half a century, and how the generational waves, both violent and beautiful, define our species. Yes, the news is shocking, but nothing is unprecedented.

Writing the poem, “Possum Dead,” I was thinking about the murder of James Byrd, Jr. in Jasper, Texas in 1998. He was a husband, and a father of three children. His mother taught Sunday school and his father was a church deacon. Three white men chained Byrd to the back of a pickup truck and dragged him for three miles. They spray-painted his face, urinated and defecated on him, and left his torso in front of a church. His body left a blood trail, and his remains were scattered in 81 places.

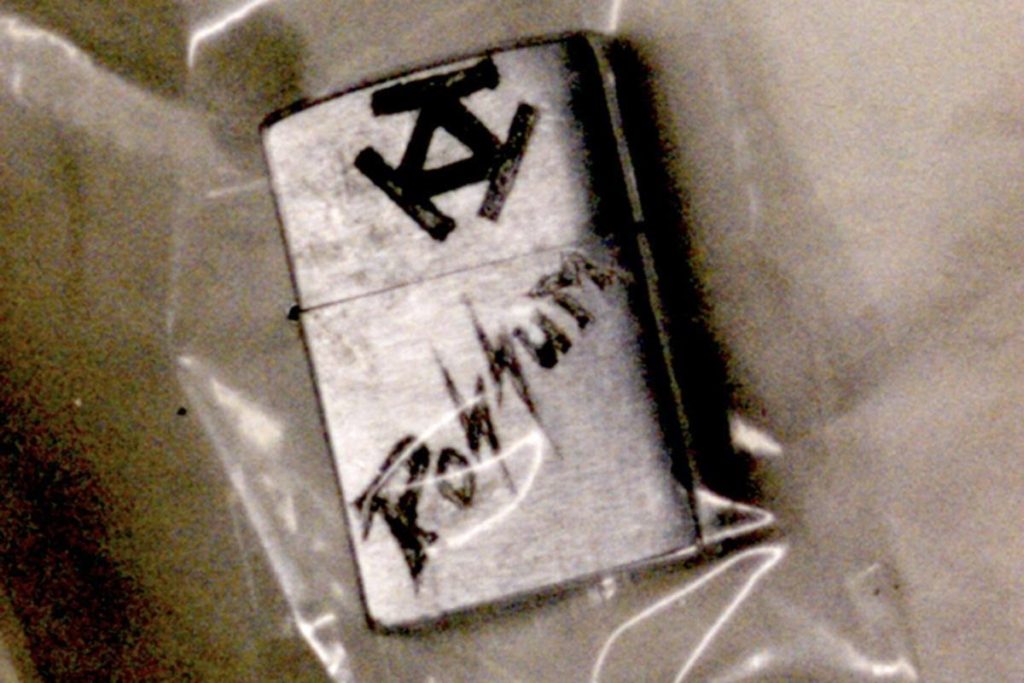

The men who killed Mr. Byrd knew him. He was comfortable enough to willingly enter their car, accepting an offer for a ride home. The police were able to track down and arrest the murderers because various items fell from the truck: a crescent wrench with the name “Berry” on the handle, which belonged to Shawn Berry, and a lighter which belonged to John King. The lighter read “KKK” on one side, and on the other side, King’s nickname, “Possum.”

When I was young, armed with a love of history and a deep suspicion of authority, I was prepared to fight my father’s generation. I saw our greatest evils bound to nostalgia. I thought racism was tied up in fantasies about the Confederacy; that Old Jim Crow wouldn’t die of natural causes and had to be torn down “by hook or by crook,” “by any means necessary.” Now that I’ve travelled a few times around the sun, and I have my own children, who delight in mocking me, and consider the things I cherish outdated, I understand the strange melancholy that creeps in with middle age. I know things about the world I hope they never learn. I’ve tried to protect them, but now I fear I can’t. I know it’s certain death if I ever fear my sons or dismissed the potential of their generation.

James Byrd was 49 years old, a year older than I am now, and two of his three killers were 23. He was old enough to be their father. Dylan Roof was still just a boy when he walked into Mother Emanuel AME Church. He prayed with his elders, then preyed on them.