I remember the moment I learned words could record the reciprocal press of poet upon the world and the world upon poet. A truant undergraduate student, I had signed up late for a “Modern British Poetry” course, and came to the second class unprepared. The assigned reading was Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Someone read “As Kingfishers Catch Fire” out loud. I had never heard anything like it. I felt a pleasure I can only describe as a swoon. I gripped the edges of the desk to keep myself upright. The sprung rhythm in combination with the alliteration was like having my head inside a ringing bell, like being the swung tongue that, in the poem, allows the hung bell to “fling out broad its name.”

I knew then, as I know now, that the poem elicited an ecstatic physical experience because Hopkins brought what in another poem he calls the “heart in hiding” to the surface of words and let its quick pulse beat there, where it could coax my own into a sympathetic rhythm.

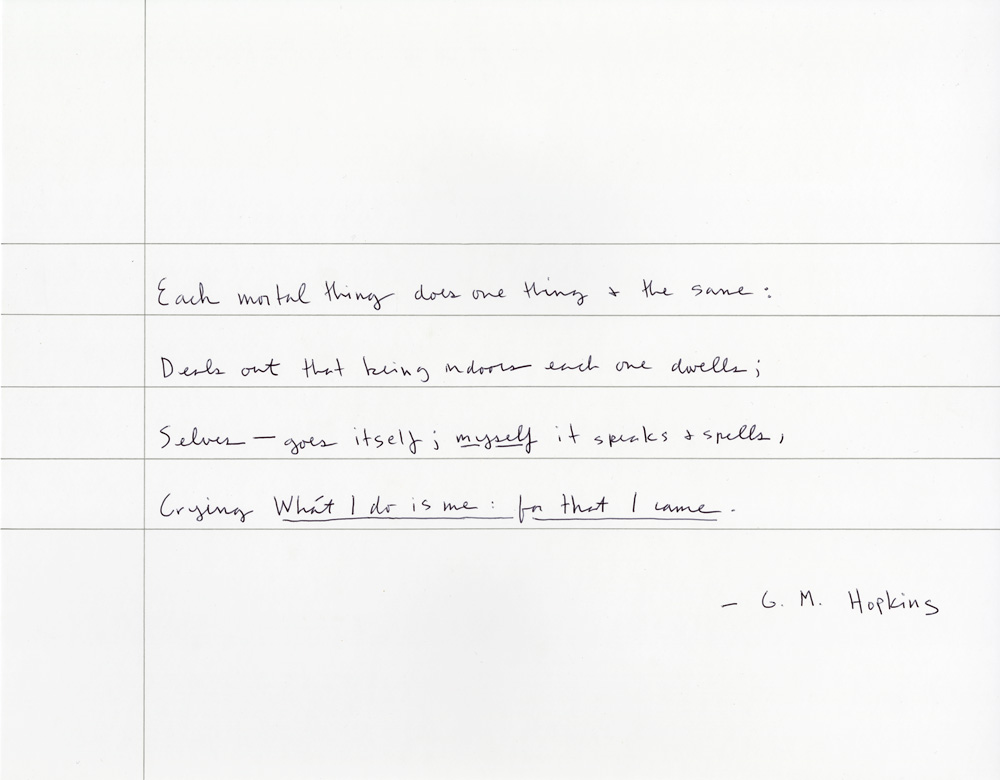

In the second half of this Petrarchan sonnet’s opening octave, Hopkins argues that

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells.

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

In other words: being is. It’s action that reveals the selves alive inside things.