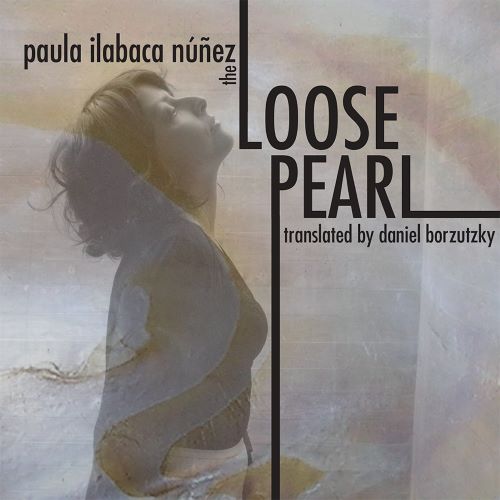

The translation I’ve chosen for Poetry Daily is from the final section of a book-length poem, The Loose Pearl, by Chilean writer Paula Ilabaca Nuñez (the translation will be published imminently by Co-im-Press). In her introduction to the book, Paula describes these poems as:

songs of desperation directed at patriarchy. A patriarchy that did not allow a young, working class woman to be single, without children, to sustain herself with her own money,…without a man interceding between her and the world. That’s how the words came out of me with anger, an anger that kept me suffering, in agony, but the writing kept me alive. Locked up in myself and fed up, locked up in a bedroom like the pearl, with my bed as the setting for the postures and poses of my voice. I lived and suffered in that writing.

The protagonist of this book is a young woman who sees herself as split in two: between the Loose One and the Pearl, different identities formed in relation to the desires and pathologies of the men who seek, yet fail, to control her. Needless to say, I cannot share the subject-position of the protagonist or the author. It was a translation that challenged me to step far outside of myself and to try to translate the language of pain and anger the book was communicating. I am mostly not talking about content here. I am talking about spirit or energy or the mystical underpinnings that breathe through and carry along the writing we love most, the writing that scares us most, the writing that means the most to us.

Translation is often discussed through a rhetoric of problems: the problem of difference, of misunderstanding, of what cannot move from one language to another. And these problems are often presented as issues of syntax or mechanics, or, more recently, issues of culture and subjectivity. Lately, however, I’ve been thinking that the real problem for the translator is the body. In saying this, I can’t avoid thinking about the relation of gender, race, and dis/ability to writing, and the ways in which a translator must acknowledge and work with radical differences in physical and social presence. Having said that (and relatedly, though perhaps more basically), what I am primarily thinking about here is physiology and the intangible ways that art comes out of our bodies.

When I write I feel words in my rib cage. I move around. I lie on the floor. I hum and murmur and repeat sounds so that they vibrate in my thighs and upper arms. I put my head down and close my eyes and listen deeply to my chest for signals that I translate into language. (Other times, I’m in so much discomfort I can’t write at all). I suspect that other writers, no matter their bodies, might say something similar about the corporeality of their processes. It’s strange to admit this: but as I’m translating I think a lot about the physiological HOW of how a book gets constructed: the physicality of dreaming, writing, thinking. I also acknowledge that every sentence I write here is posing a set of problems that I cannot remotely do justice to in this paragraph. Writing is scary this way. Silence also lives in a body and must be translated from one poetry to another.

Or, as Edmond Jabès writes (translated by Rosmarie Waldrop):

The real silence is death and this is terrible. To approach this silence, it is necessary to journey into the desert. You do not go into the desert to find identity, but to lose it, to lose your personality, to become anonymous. You make yourself void. You become silence.

To bring this back to The Loose Pearl, what the Pearl and the Loose One carry inside of their bodies manifests as dread and malaise. The protagonist retains and resists psychological abuse; she is “split in two by this flurry of blows delivered to that thing that everyone refers to as my face.” In another section “The loose one breathes melancholically while she comes down with diarrhea; the pearl acts like it’s nothing….as if nothing were running through her, just so, with her usual nonchalance; then they look at each other and swap roles, swap conditions and souls.” A parasite is ‘boiling in her belly,’ as she is consumed by pain and infection.

The problem of translation here had to do with how to communicate both affect, absence and physicality; how to transmit desire as affirmation; how to translate the unknowable experience of abjection appearing as duality (two personas in one body); of abjection fluctuating between depression, anger and, ultimately, the refusal of subjugation and humiliation within “extremes of blankness” as the pearl constructs herself from “herself into herself.” Moans, spasms, abandon, obstinance, denial, absence: the translation problem of the body was about how to make poetry out of the complex formation of identities that cannot be contained by language. I thought a lot about the lives on the page. I constructed histories for them and tried to imagine different ways they might frame the realities and mythologies of their bodies. I sent hundreds of silly emails to Paula asking questions about worlds inside of worlds, words inside of words, bodies inside of bodies. Without her generous answers this book would surely be different.

A few years ago I had a recurring dream about translation (which is to say I wrote a recurring poem about translation): I was translating a dead poet and I went to his hometown because I decided that I could not translate the poet without knowing exactly what was going on inside the poet’s body. I, the translator in the dream-poem, was overwhelmed by the need to know what the poet was physically experiencing at the time of writing. And I wanted to know something about the bodily sensations or experiences that then came out as poems. What did this mean, inside the poet’s body? In the dream-writing I came to believe that I could not translate the poet if I did not know something about his bones, his liver, his kidney, his lungs, his blood. How did his heart function? What minerals and vitamins did the body and the blood possess? What was missing? What was corrupted? What was broken? What was silent? What was silent? What was silent?

These dream questions are of course impossible for any translator to really know. And in a certain sense they are fairly useless when you sit down to the work. Nevertheless, I held on to them. And I thought about the way in which my own writing, my own writing spirit, my own writing body, the unknown energies I conjure up on the page, all exist in relation to the writing that means the most to me.

Paula and I share a fondness for Marguerite Duras and Alejandra Pizarnik, whose words serve as epigraphs to The Loose Pearl. And so as I translated this book, over the course of several years, I kept consulting the work of Duras and Pizarnik, as well as Paula’s other books. And I felt, for better or worse, that these consultations might help me to figure out something about the spirit of the work, its energies, its underlying silences and pains and mysticisms.

For decades, I have been obsessed with these ‘absent-words’ from Duras’s The Ravishing of Lol Stein (translated by Richard Seaver). And I kept coming back to them over the long period of time in which I was translating The Loose Pearl.

It would have been an absence-word, a hole-word, whose center would have been hollowed out into a hole, the kind of hole in which all other words would have been buried. It would have been impossible to utter it, but it would have been made to reverberate. Enormous, endless, an empty gong, it would have held back anyone who had wanted to leave, it would have convinced them of the impossible, it would have made them deaf to any other word save that one, in one fell swoop it would have defined the future and the moment themselves. By its absence, this word ruins all the others, it contaminates them, it is also the dead dog on the beach at high noon, this hole of flesh.

The dead dog on the beach at high noon. The hole of flesh. The hole in which all other words have been buried. I lived with these images and tried to let them suffuse the soul and the spirit of this translation, while also allowing the soul and the spirit of The Loose Pearl to suffuse and affect me.