Rosselli, Rimbaud, Lilies, Lilacs and ‘H’

Let me start with a rookie mistake I made long ago in an early draft of this translation, a mistranslation of “lilies” for “lilacs.” I saw the correct translation projected on a large screen at an Amelia Rosselli symposium hosted by Barnard College in the spring of 2011. And yet my blunder was serendipitous, as it led to my working with my current co-translator, Roberta Antognini. I still remember drinking red wine with Roberta after the day’s proceedings and seeing the picture of a flower, undisputedly a sprig of lilac, that came up on her cell phone as she double checked the word. The end result was more poorly suppressed tears on my part, more pouring of red wine, and, ultimately, the birth of an excellent partnership.

But back to blundering. When I saw reading the Italian phrase “i lilla’ della vallata,” I’d fallen into a trap set by the tri-lingual and often impish Amelia: I’d reached for the biblical and lyrical phrase “lilies of the valley” as somehow appropriate for Rosselli’s Ortensia who I initially imagined as a hardworking prostitute renowned for her “ejaculatory mechanics.” (She was going to have her dignity even in her degradation.) Except that the phrase literally translates as “lilacs of the valley,” far less biblical and both flaccid and phallic…a lot more like the scurrilous spirit of the Rimbaud passage Rosselli was riffing on. And I am going to claim that, oddly, my rookie mistake had a tiny bit of justice to it.

“Libellula” means “dragonfly” in Italian, but it also contains the word “libello,” which means both “libel” and “pamphlet” (the poet’s long poem or “poemetto”). La Libellula / The Dragonfly is a libelous long poem, containing as it does Rosselli’s exuberant riffs and deliberate deformations of poems by her own mentors, including, but not limited to, Dino Campana, Eugenio Montale, and, as we find in this passage, Arthur Rimbaud. These riffs generate the body of the titular dragonfly, the loops of whose flight, characterized by “disenchantment, / enchantment and frenzy,” reverberate throughout The Dragonfly.

What I hope comes through in my and Roberta Antognini’s translation of this passage is the obsessive insistence with which Rosselli demands we search for and find Ortensia, and how equally insistently the text embodies a desire that is somehow delicate, hermetic and insatiable by turns. Rosselli takes the onanistic, gratingly abrupt though brilliant original and gives it a brand new lyrical body along with a new subjectivity to inhabit that body—an actual, if enigmatic, character as opposed to what is, in the original, basically a genital spasm.

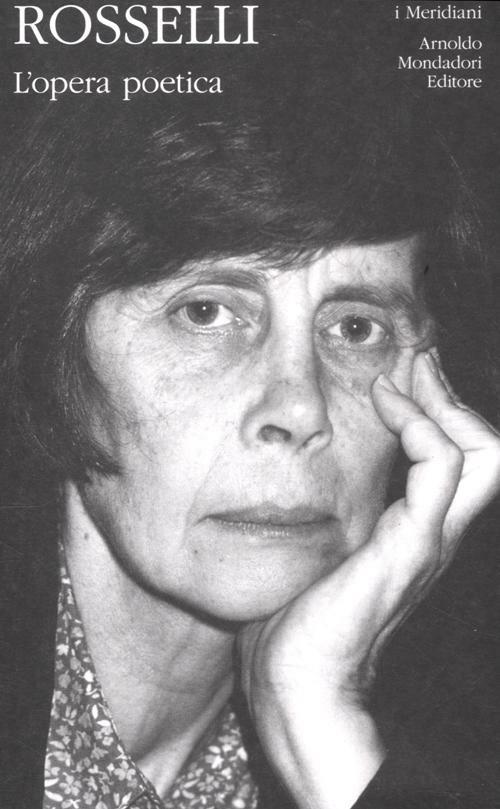

Rimbaud’s “H” has been variously identified as short for Homosexual, Hashish, the outhouse, female masturbation, and even Marie Antoinette’s trip to the guillotine. Rimbaud does, in fact, go on to identify his protagonist as “Hortense,” though granted Hortense could well be code. Offering my own reinterpretation, this Hortense / Ortensia might stand in for Rosselli herself, who lived in an equivocal historical and personal space “populated by the specters” of her father, Carlo Rosselli, and her uncle, Nello Rosselli, who were assassinated by Mussolini’s operatives in the south of France when Amelia was a child. Rosselli’s desire to be part of the Italian and international poetry community was increasingly thwarted by the socially isolating symptoms of her paranoid schizophrenia, an illness that developed partially in response to the trauma and dislocations she underwent as a child and that eventually led to her suicide in 1996. When she moved to Italy as a young adult, settling first in Florence and then permanently in Rome, Rosselli came as a foreigner to the land of her father, uncle, and paternal grandmother, also a writer and also named Amelia Rosselli. (Rosselli’s mother, Marion Cave, was British.) Some commentators feel this gave her permission to hear Italian in a new way.

The Dragonfly, an early work of Rosselli’s (1958) is a unique text of reverberating adaptions and deformations that harbingers our contemporary embrace of writing as rewriting and also correctly intuits in the Rimbaud assemblage the great solitude that so often visited this great poet.

*

Entre Ríos Books will publish the translation of The Dragonfly by Roberta Antognini and Deborah Woodard in 2023.