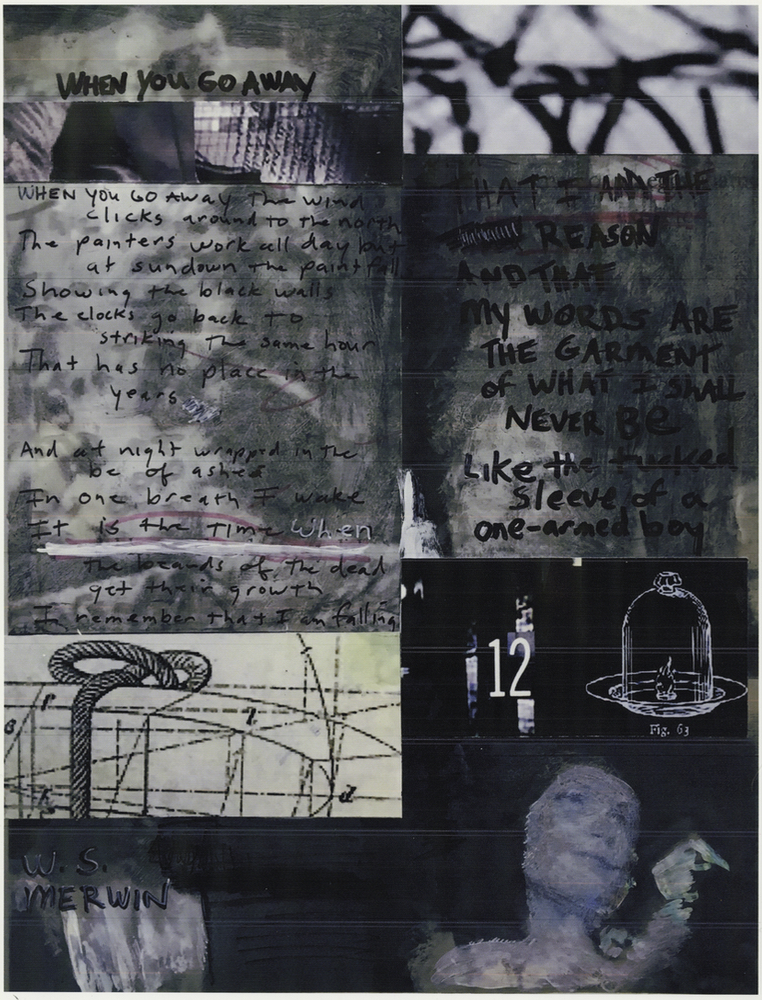

How, I had wondered—an undergraduate led to W. S. Merwin’s The Lice by my teachers Marcia Southwick and Larry Levis at the University of Missouri (it must have been 1979)—does one redeem a tired, conventional lyric subject like longing? The premise of “When You Go Away,” is familiar: when the lover is separated from the beloved, the order of the world changes. Given the limits of this conventional subject, how did Merwin make a thing both faithful to its convention and new? I found an answer to my question in the complexity of the poem’s final lines: “my words are the garment of what I shall never be / Like the tucked sleeve of a one-armed boy.”

In the line preceding those last two, the lover recalls that he is “the reason,” but the reason for what? The beloved’s departure and present absence? The lover addresses the absent beloved, but absent, how can he be heard? His words are a “garment,” but what is their function? Do they shelter the body? Do they ornament the body? Do they cloak and conceal the body? Do they wrap and reveal the body?

Then, in the second half of that penultimate line, the garment metaphor is modified, and while the metaphor becomes more specified by that modification, it becomes more various and tangled as well: “my words are the garment of what I shall never be.” The speaker’s words clothe a future negation, not so much of the beloved’s absence, which thus far has been the subject of the poem, but of what the self—the lover—will not achieve. What is that? I do not know, and when I think the next and final line will answer all the above questions, it instead adds to them. The metaphor of the word-garment is further modified by a simile: “my words are the garment of what I shall never be / Like the tucked sleeve of a one-armed boy.”

In what way are his words, which are garments, like the garment that is “the tucked sleeve of a one-armed boy”? Are his words meant to expose or hide a lack? Is the tucked sleeve an image of what fails to fill it—the boy’s missing arm? Or is the sleeve, tucked, not dangling, an attempt not to call attention to that which is missing—the phantom limb that feels but is not there? These are the sorts of questions I was asking myself when I first came upon the poem and the intricacy of this image. I am still asking them. But I realized then that it is the marriage of convention with the particular and peculiar vision of an individual poet that can redeem the conventional from all its previous iterations, that one must not avoid the conventional, but play one’s individual changes upon it.