I initially wrote this poem along with my students in a poetry workshop, following a prompt to retell, untell, adapt, or mutate a myth, using a personal experience as a starting point. The four “objects” I considered together in the writing are all texts, of a kind: David Ferry’s poetry collection Bewilderment, which includes parts of his translation of The Aeneid; Bernini’s sculpture “Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius,” which I’d seen at the Borghese Gallery in Rome the year before; a piece by Swedish artist Susanna Hesselberg, titled “When My Father Died, A Whole Library Burned Down” (the title of which is inspired by a Laurie Anderson lyric), which I’d seen online; and finally, a book I’d read many years before, Genome, by Matt Ridley.

My father had recently died, just a few weeks after my son was born. During most of the interim period, I was staying at my father’s now empty house, with my days-old baby and his big sister, then two, trying to take care of, and advocate for, my father in the ICU while keeping everyone alive and happy at home. My son, after an emergency birth by C-section, rarely cried, and woke up only to eat. My father was in a liminal state, often awake, but very sick and unable to talk or write most of the time. I had the sense, borne of my own exhaustion, that the two of them were communing in a bardo together, and only one might come back.

My father had respiratory failure due to a fall; a spinal injury had caused his chest to fill with fluid. I agonized over whether to put him on a ventilator as his organs began to fail, though the hope of recovery was exceedingly slim. In the end, once I learned he’d have to be in restraints on the ventilator, I decided against it. I could not let him die that way. As I’ve read about Covid patients suffering as they go on and off of ventilators, and struggling with ICU psychosis, as my father did, I’ve been constantly reminded of the feeling of making impossible decisions, decisions most of us aren’t prepared to make, and yet, decisions we have to live with.

For me, Virgil’s Aeneid is partly about continuity and repetition, a setting out over and over again. Likewise, David Ferry’s deep intertextual approach to writing—especially in Bewilderment, which includes his translations of Virgil, Catullus, and others, alongside his original poems—is also about continuity and iteration. Ferry has influenced all the writing and translation I’ve done, and this poem in particular is inspired by the end of his “Reading Arthur Gold’s Prose Poem ‘Allegory’,” where Ferry writes:

Their little children, they have all come back

From the Underworld, bringing their DNA

Unknowingly in their little satchel bodies

Like Aeneas bringing with him, in a satchel,

Troy, and his household gods, and watching him,

Wherever he was going, the terrible great

Gods who might turn against him any time soon.

At the time I read this, I was thinking about the same story as depicted in Bernini’s sculpture. Aeneas and his people flee the “wasted city” of Troy, looking for a new home. He walks with his son, carrying his father. I felt so moved by this image of Aeneas carrying his father, who, in turn, carries the “family gods,” the altar this family uses to make meaning of their lives, to pass down a sense of continuity. I wanted to carry my father to safety, to “carry him away,” as the poem says, every time he asked for his car keys and begged me to remove him from that place. But I failed. He died in hospice while I struggled with the palliative care coordinator about the risks of air hunger and morphine debt.

The statue became a touchstone for me, a portrait of the “sandwich generation,” older parents who care for their own parents and young children at the same time. In the aftermath of all of this, I began thinking about Matt Ridley’s Genome, which argues that all biological life, including human life, can be seen as a vehicle for DNA’s evolution of itself. To be clear, he actively discredits ideas of eugenics in his book, and I wasn’t thinking of the particular biological connection between myself, my father, and my son, but of this notion of having sprung from a matrix of energy and intelligence, into a world in which “I” briefly exist. The title of the poem plays with this idea, as if it’s a fable told to this intelligence, in which human beings facilitate a kind of lesson.

In this moment of primal feeling for two precious beings in my care, I had a sense of being a conduit, an inheritor of my father’s determination and heart, now passing it on. But this sense was accompanied by a sense of connection with all creatures threading the needle between life and death, and imbuing the process with meaning. The pressure of that time made my identity more porous. Perhaps that porousness is reflected in the way the many “objects,” or texts, intersect in the poem.

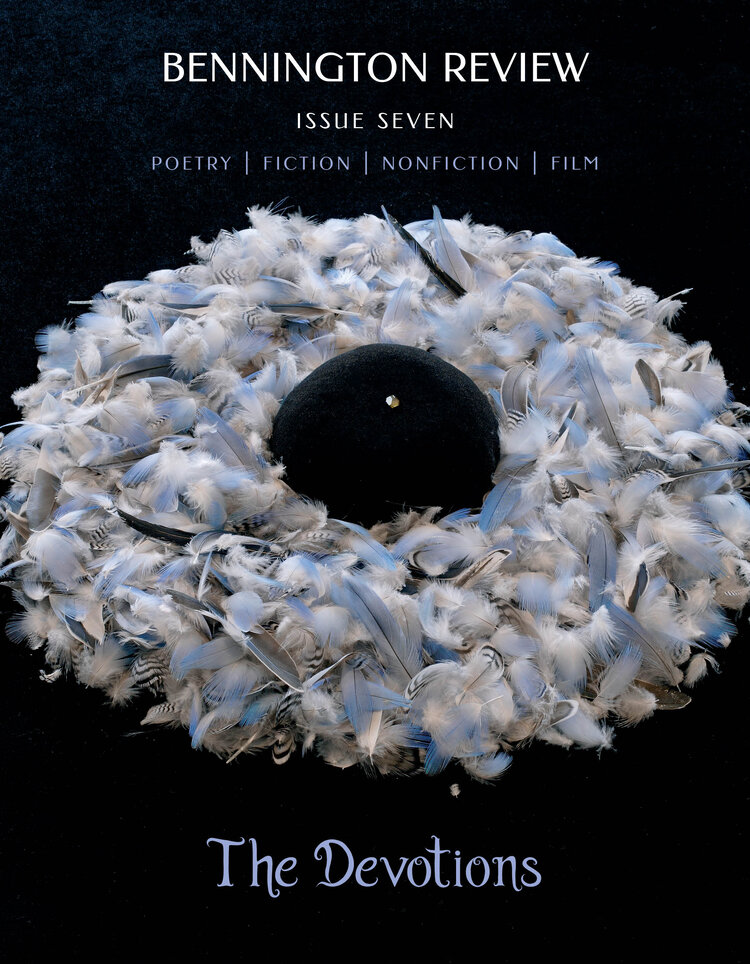

Photo: “Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius” by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1618-1620, marble, Galleria Borghese; Rome, Italy.