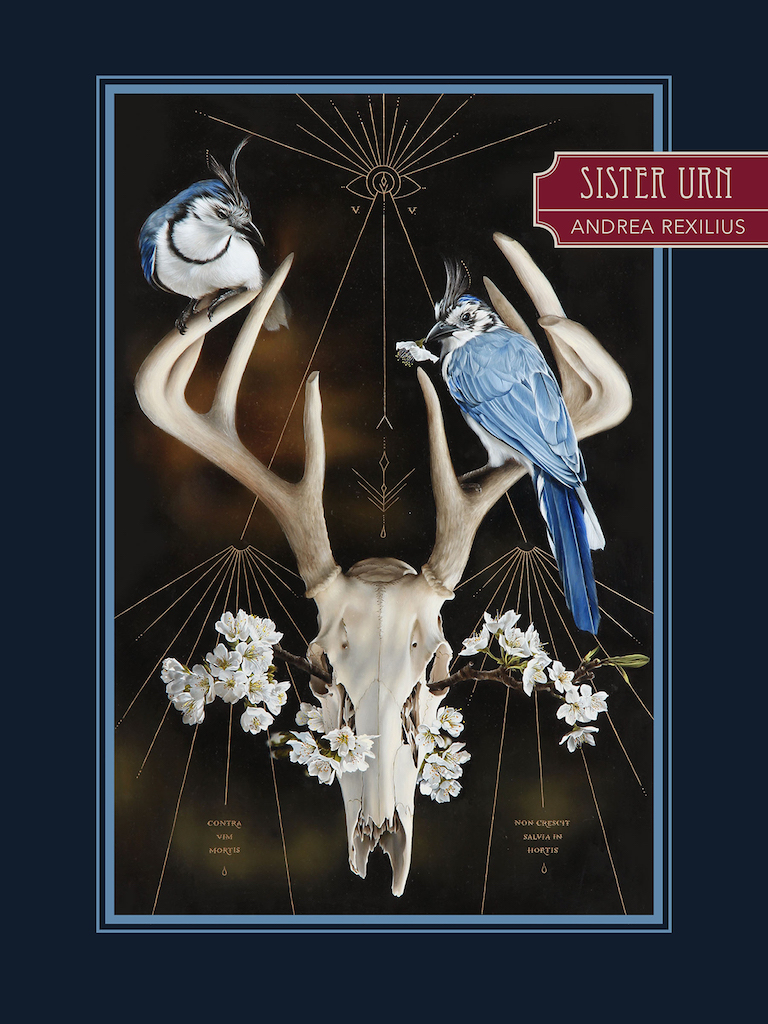

Andrea Rexilius’ haunting Sister Urn (Sidebrow Books, 2019) eulogizes the loss of her sister Andrea to a drug overdose. The poems in Sister Urn spear like broken glass through the palm, emancipating us from Cartesian solitude and into the holy space of conjoined mortalities. Her lyricism crafts a cathedral to house both the heaven our bodies were and the hells the flesh must endure. In Sister Urn, memories hunt for their other half in forms now mourned, and, in death, ripen into meadowlark and tree branch. Rexilius writes in a statement for the Poetry Society of America, “I became interested in how one Andrea’s experience might hide the other’s experience and how disclosure of personal information was both masked in this way and also shared by the two selves whose intimate details were being entangled.” While she writes this of the opening poem in the collection, “Andrea/Hem,” her statement captures the fraught interpenetration of identities the book weaves: as she writes in “Unstitch,” “I sew my tongue to my sister’s tongue so we can speak as one Andrea”; or, as she writes in the one line poem “Self-Edge,” “In a poem, one Andrea may hide another Andrea.” Her stepsister’s death, as the book details, continues on, hidden in “another Andrea.”

The courage to write of death, let alone the passing of a sister whose life, language, and world were so intimately connected, who shared one’s own name, awes me. In Sister Urn, Rexilius swan dives into the wound, into her loss, articulating grief with such intimacy that it wounds and this wound becomes the very breach allowing for communion. Rexilius’s previous books, To Be Human Is To Be A Conversation (Rescue Press, 2011), Half of What They Carried Flew Away (Letter Machine Editions, 2012), and New Organism: Essais (Letter Machine Editions, 2014), explore the depth of epistemic entanglement in sisterhood. In Sister Urn, Rexilius opens this entanglement and shares with the reader how death is a communal experience, how her sister’s death inhabits her own body, living on within both her flesh and her language. When reading these texts, one is drawn to ask, How does one write of a death that continues in one’s own living lungs? How does one write of a loss so intimate, of a relationship so interpenetrating, that to hear one’s own name is to be cast again into loss and absence?

“Gravity” from Sister Urn addresses how Rexilius navigated the knowledge of her sister’s passing on social media, the kinds of questions received there. In conversation, Rexilius has told me “Gravity” was the first poem she wrote after her sister’s passing. She writes, “This is the line of outcome.” Cause and effect, the consequence of action, the poem announces that it will attempt narrative in order to account for the unaccountable. Edging toward the hermetic brevity of Paul Celan, the poem images the “Gravity of a vein’s collapse,” the thin walls of the sister’s failed heart, how, “afterwards, we gathered you/into pails and buckets.” Rexilius’ taut lines condense the narrative of her sister’s dying into images of outcome. We, the reader, are witness to only the consequence of addiction. We, the reader, become voyeurs attempting to piece together the “why” of the sister’s dying. While promising a “line” of outcome, the poem itself fragments the attempt to offer a coherent whole. The poem can only image traumatic flashes of sensory insight.

“Gravity” resolves with a couplet and a tercet. Rexilius writes, “Still, everyone will say/what was it like to lose a sister//What was it like to see her body/embalmed within church walls/in your hometown.” While syntactically structured as questions, the lines are punctuated with periods. Rexilius, in conversation, stated she wrote these lines to capture the kinds of questions she received on Facebook. These lines, syntactically posing as questions, capture the impossibility of response in punctuation. The period is silence. The period is the impossibility of publically clarifying trauma. The period is “the line of outcome” when faced with the crude narrative constructed when social media accounts for loss.