Rendering Outside Time

Growing up, on a near daily basis, I’d visit my grandmother’s home in the “Spanish colony” just outside of Greeley, Colorado’s city limits. Just across the Poudre river, sandwiched between corn fields, the colony was where, every weekend, my cousins, uncles, and aunts would gather in the dirt backyard of my grandmother’s adobe home. No matter the time, morn or twilight, entering her house you’d smell the soft warmth of tortillas and fried chorizo. You’d hear the laughter of my uncles or aunts as they lightly teased each other about some memory. You’d see, on the walls, large frames with templates to hold a dozen or more 5×7 photographs. These collage-like photo frames held lifetimes of memories and identities. With photos from the 1930s to the present, the geometrically uniform frames were singular portraits of a family. In one such frame, the frames of generations: in the top right, a photo of Laredo, Texas where my great grandmother, in front of a two-room house, stands beside a lemon tree with my mother (three or four years old); to this photo’s left, my grandmother looks at the camera as she sits, leaning against a young tree in front of her house in the colony thirty years after the Laredo photo; under this image, my aunt, a teen in the early 70’s, sits on a car hood where, in fifteen years, her mother will plant a tree1.

*

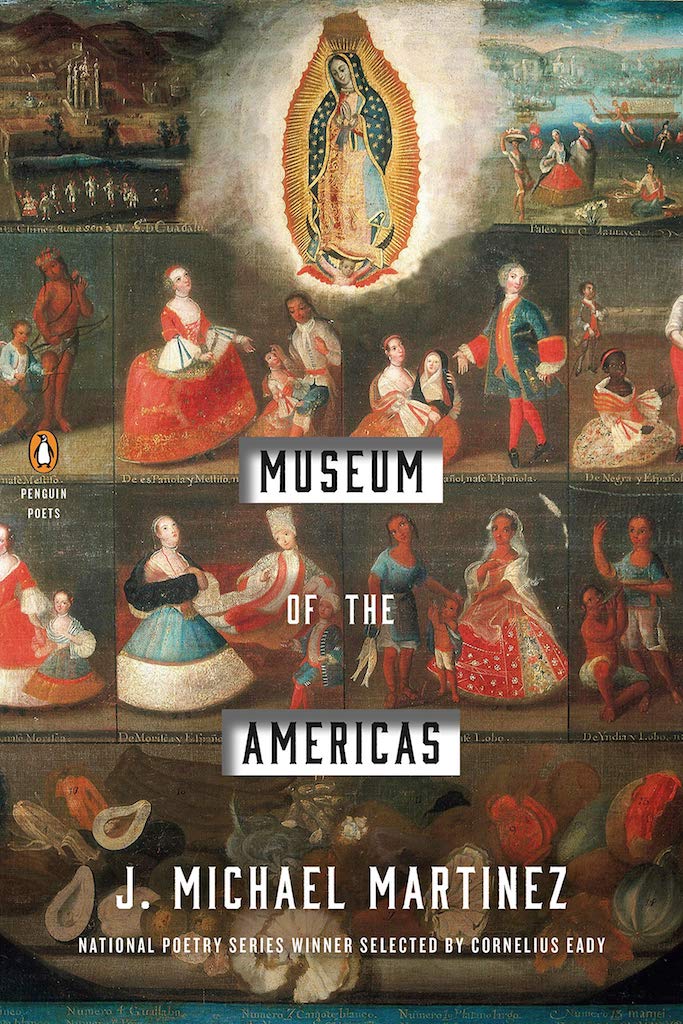

In my last book, I wrote on casta paintings of New Spain from the early modern period. Appearing uncannily similar to the photographic frames hanging in my grandma’s house, these oil paintings on canvas were paneled; however, each individual casta panel pictured and named/invented, often for the first time, a racial caste; the painting as a whole was frequently the portrayal of a single individual’s racial heritage. The casta paintings were attempts to quantify and taxonomize “whiteness” for the ruling bodies of New Spain—if one’s heritage was “white” enough, you enjoyed particular liberties. If you are interested, Dr. Magali M. Carrera, in her Imagining Identity in New Spain, charts the vast web of identities manufactured by the casta paintings in the pursuit of racial purity2. The racialized body of New Spain relied not solely on the visible “color” of the actual body but on what this color meant historically: what races mixed, or to be crass, copulated and conceived the body in question.

*

Also in my last book, I wrote of a number of early 20th century postcards produced by one Walter H. Horne. The postcards picture lynchings, executions, and mass gravesites of Mexicans and ethnic American citizens, their bodies the focus of the photograph. Ken Gonzalez-Day, in his Lynching in the West, traces in detail the 19th century U.S.’ popular physiognomic condemnation of the mestizo, stating, “[they] were thought of as being a half-breed race, scarcely above the indigenous ‘Indians’ who were regularly portrayed as primitive or savage peoples3.” The Greaser Act of 1855 illustrates Gonzalez-Day’s conclusions: the Greaser Act, an “anti-vagrancy” law, conflates race and criminality; section two of the act directs the law at “all persons who are commonly known as ‘Greasers’ or the issue of Spanish or Indian blood…[they] are not peaceable and quiet persons4.” Here, the bodily miscegenation of the “greaser” is legally condemned for it supposedly results in, “not peaceable and quiet persons,” but in criminal, vagrant bodies. Occurring shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe, the Greaser Act was used to appropriate the land of both wealthy and impoverished Mexicans, Native Americans, Californios, Mestizos, and other peoples of color. These prejudicial physiognomic beliefs can be found extending to the late 19th century. In 1899, journalist William R. Lighton wrote in the Atlantic Monthly:

Largely discredited in the 20th century, Johann Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy enjoyed great popularity in the 19th century. The book promoted the equivalency of morality with corporal beauty or monstrosity. In Lavater’s view, criminal and/or aberrant behavior could be read in the face. He wrote, “A Monster is a living and organized being, who has a conformation contrary to the order of Nature, who is born with one or more members too much or too little, in whom one of the parts is misplaced, or else is too great or too little, in proportion to the whole6.” A monster is a creature of either corporeal abundance or scarcity. Ken Gonzalez-Day, in his Lynching in the West, traces in detail the 19th century U.S.’ popular physiognomic condemnation of the mestizo, stating, “[they] were thought of as being a half-breed race, scarcely above the indigenous ‘Indians’ who were regularly portrayed as primitive or savage peoples7.”

Tracking the use of Lavater’s theories in condemning and justifying the lynching of Spaniards/Greasers/Mexicans from mid to late 19th century California, Ken Gonzalez-Day writes, “Difference was synonymous with the monstrous, and its containment served to ensure that existing social and economic and political relations would remain constant8.” The 19th century employed the false science of physiognomy to allegorically visualize the mestizo/Mexican/Greaser as a monster of physical and ideological/moral excess in order to uphold the normative social hierarchy.

*

Allegory, as Walter Benjamin has stated, is not simply a literary trope, it is also, in his words, “a way of seeing.” Critic Craig Owen notes in his “The Allegorical Impulse,” “Allegory is an attitude as well as a technique, a perception as well as a procedure 9.” The methods by which the Latinx body is visualized is instituted through the apparatus of allegory: in now classic criticism (read Anzaldua), the body is rendered as overflowing with a mythic, decolonizing Mexica/Aztec inheritance; in pop culture, the Latinx body is still often rendered visible as an event of corporal abundance and, consequently, a site of sensuous decadence/immorality. Trump’s recent racist rants about “the Mexican” are unoriginal and are themselves revelations of how much has not changed from how bodies of color were depicted in the 19th century.

*

Museum of the Americas, as a whole, speculated on these ideas of vision, of rendering bodies visible, and, therefore, as a kind of corporeal knowledge owned, sold, and, sometimes, loved. In the book, I hoped the boundaries distinguishing the body (aesthetic form) of the art work from the corporeal body represented in the art work would collapse; these entangled bodies would be, as consequence, revealed as sites of allegorical exchange between temporalities, past, present and future, time embodied by the grotesque accumulation of genetic inheritances (de)composing the speaker.

That all I said, I wanted to write of hope, I wanted to write of home: my grandmother’s house in the colony where I spent so much of my childhood. “The Wake of Maria De Jesus Martinez” was one attempt to write, as form, a casta-like poem, where each section of the lyric was itself of a different time and space, yet, linked through repeating phrases. As the lyric progressed, the work began to be less “pictorial” and relied more and more on sound: the emotional labor of the poem was performed/rendered through its music. The lyric’s music I see now as one attempt to linguistically maneuver outside time, speaking to both my grandmother’s passing, her still-living presence, and to perform a rendering with love.

I don’t know if that was accomplished, but I do feel one must immerse oneself in the maze in order to even begin to imagine an exit (if one such exists); likely, as the maze itself is the very notion of community, I wonder, how does one decolonize justice so that the idea of the so-called “social contract” recognizes and resolves itself for and with the communities it excludes, into, what is now, a future only recognizable to us by the tattered remnants of our own limited imagination of “hope?” How does one lead an unrealized dream to a higher stratum? How does one lead fantasy to a more inclusive vision whose limits, themselves, will constantly flux and fold as this community constantly adjudicates the very foundations of imagining?

__________________________

1 Martinez, J. Michael. “Wake of Maria De Jesus Martinez,” Museum of the Americas. Penguin: NY, NY. 2018. Pg. 75-85.

2 Carrera, Magali M. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

3 Gonzalez-Day, Ken. Lynching in the West. Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 28.

4 Heizer, Robert F. , and Alan J. Almquist. The Other Californians: Prejudice and Discrimination under Spain, Mexico, and the United States to 1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

5 Lighton, William R. “The Greaser.” Atlantic Monthly 83, no. 500: 750-56.

6 Lavater, Johann Caspar. Essays on Physiognomy: Designed to promote Knowledge and the Love of Mankind, Illustrated by More than Eight Hundred Engravings Accureately copied; and Some Duplicates Added from Originals. Executed by, or under the Inspection of, Thomas Holloway. Trans.

Henry Hunter. London: J. Murray, 1789-98, 4:188.

7 Gonzalez-Day, Ken. Lynching in the West. Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 28.

8 Gonzalez-day, pp. 159

9 Owen, Craig. “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” ed. The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology. New York: Oxford Press, 1998.