When W. B. Yeats first published the series of poems he years later called “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” he titled it “Thoughts upon the Present State of the World.” The present becomes the past when we read the later title in The Tower, published in 1928, but for Yeats the series (he always called it a series) never stopped being written during the Great War (as World War I was called then), the Russian Revolution, the Irish Revolution, and the subsequent Irish Civil War. In the caustic first section we run headlong into the unprosecuted murder in Kiltartan, County Galway, of Eileen Quinn by British troops.

a drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free.

Here, unlike in the more famous “The Second Coming,” in which Yeats references current events in the drafts (“The Germans are [ ] now to Russia come”) but eventually mythologizes them (“Things fall apart”), Yeats wants to be something like a documentary historian. He folds the murder of an Irish woman into his groping account of the strange death of British liberalism, and that death is happening now.

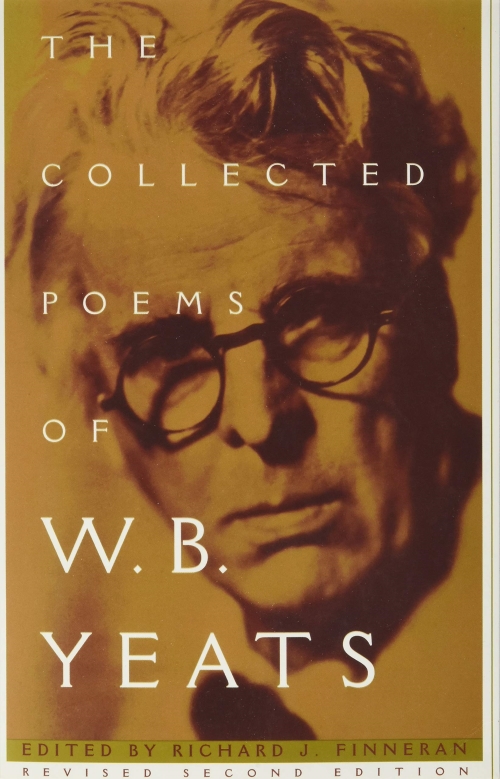

The series seemed to me scary in a way poems rarely are when I first read it in 1981; it seems if anything more so today. “O what fine thought we had because we thought,” says Yeats, and a couple of months ago that iambic pentameter line shot out at me as it never had before: is thinking itself the part of the problem, the way we depict thinking in language, the way we’ve learned to recognize it?

The series also contains this poem, four lines, trochaic tetrameter.

We, who seven years ago

Talked of honour and of truth,

Shriek with pleasure if we show

The weasel’s twist, the weasel’s tooth.

Boom, end of poem, end of section. The willingness to be so brief, so primitive, is I think part of what makes “Thoughts upon the Present State of the World” so discomfiting, and that willingness is magnified because its six sections have at large little to do with one another. The first poem (from which I’ve quoted the lines about Eileen Quinn) consists of six stanzas of ottava rima, that otherwise stately stanza imported from Italy, parts II and III are written in Yeats’s most elaborate stanza, a ten-line monstrosity, and part IV consists only of the primitive quatrain I’ve just quoted. Part V consists of four song-like stanzas of five lines each (“Come let us mock at the great”—“Mock mockers after that”), and the visionary final part consists of eighteen grand pentameters.

Have we got all that? I don’t think so: what matters is that we feel the growingly uneasy disparity, the parts somehow adding up to a whole but the whole also rejecting them. The difference between sequence and series was codified by nineteenth-century German mathematicians, and today we really ought to speak not of the World Series but the World Sequence: the order, producing one end, matters.

Yeats doesn’t write his series that way. Is there a longer poem bleaker than “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen,” a poem more resolutely written against the consolations of poetry while at the same time wildly employing all the mechanisms of poetry—a poem more bleakly written against itself? This longer poem, in the relationship of its pieces, has been creepily influential on poets as disparate as T. S. Eliot (who first read it in a magazine before he wrote “The Waste Land”), George Oppen, Adrienne Rich, and a lot of poets writing today.

O what fine thought we had because we thought.