Seldom does a writer in English move between verb tenses in the same work. James Salter is one exception: in his novel Light Years, written in the past tense, there’s a scene between two lovers in which an erotically charged moment is suddenly and briefly rendered in present tense. The ending of John Ashbery’s poem “This Room” makes a similar move, shifting from past to present, creating a poignant immediacy:

We had macaroni for lunch every day

except Sunday, when a small quail was induced

to be served to us. Why do I tell you these things?

You are not even here.1

These are exceptional departures, notable for their clarity in meaning despite their transgressions. But they also suggest a way of thinking about how to translate time when working with languages like Chinese that do not have verb tenses.

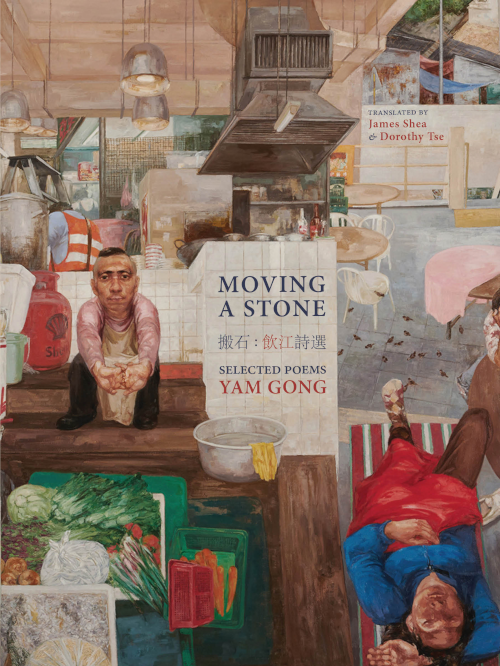

Capturing the flow of time in “Startling Hair” by the Hong Kong poet Yam Gong was typical of this sort of challenge. There’s a fair amount of flexibility in how to interpret the sense of time in Chinese, known for its “tenselessness,” as a charming term from linguistics describes it. In “Startling Hair,” time itself is part of the subject—on multiple occasions, years pass by in a single phrase. The line “spring flowers bloom and the autumn moon wanes,” for example, is a metaphor from classical Chinese that refers to the passing of time. In the opening lines, Yam Gong’s poem moves back and forth from the present to the past, but eventually settles on a string of childhood memories of getting a haircut, initiated by a word in Chinese (nà shí) that can mean “in those days.” My co-translator Dorothy Tse and I, however, took a small gamble by shifting to present tense for the speaker’s memories. We felt there was an opportunity to signal the fluid sense of past and present in the Chinese, so we used an em dash to prepare the reader for a shift in temporal perspective. Tense cannot be avoided in English, so by mixing verb tenses in the translation, we tried to dislodge the reader from being fixed in a single tense. Matching the Chinese, we also omitted periods, using only capitalized first words to mark the start of a new thought, which we hoped might further create a feeling of simultaneity for the reader.

The verbs that follow (“smiles,” “rests,” “sit up,” etc.) are neither in past nor present tense in Chinese, and so they do not necessarily remind the Chinese reader that the action is happening in the past; the main impression is of the scenes unfolding in vivid detail. Instead of verb tenses, Chinese relies on other devices to provide a sense of time, such as temporal adverbials (e.g., “yesterday”), modal verbs (e.g., “will”), aspectual particles (e.g., zhe, akin to “-ing”), and even plain common sense.2 The lack of verb tenses (specifically, “no tense declensions”), combined with other grammatical features of Chinese, allows a great deal of perceptive freedom, as noted by the scholar and translator Wai-lim Yip. He argues that the flexible grammar in classical Chinese poetry—e.g., the lack of articles, personal pronouns, and tense declensions, along with the sparseness of prepositions and conjunctions—creates an “open space:”

with the poet stepping aside, so to speak, [readers] can move freely and approach the words from a variety of vantage points to achieve different perceptions of the same moment. They have a cinematic visuality and stand at the threshold of many possible meanings.3

Our tactic for depicting the memories in Yam Gong’s poem is found in a good deal of English verse, and has been called “the tense of timelessness”4 or “lyric tense.”5 Emily Dickinson provides a good example: “I see thee better—in the dark—.”6 But Yam Gong’s speaker does not remain in an idealized state of timelessness: he returns to the present (“don’t look in the mirror much anymore”), and the last lines imply that he’s learned something from life, perhaps something unwelcome.

The poem’s recollections are like looking into a mirror, reflecting back on oneself and the central figure of the mother. An allusion further extends the poem back in time to the Tang dynasty. The poem’s title, as well as the image of the mother’s hair turning white overnight, evoke lines from the classical Chinese poem “Bring in the Wine” by Li Bai (701–762):

Look there!

Bright in the mirrors of mighty halls

a grieving for white hair,

this morning blue-black strands of silk,

and now with evening turned to snow.7

An almost manic call to seize the day, Li Bai’s “feast poem” celebrates enjoying life while we’re still young. In Yam Gong’s hands, however, the traumatic image suggests the mother’s stress at raising her family. The speaker recalls that his mother asked for her sons’ heads to be shaved bare. As the speaker grew older, he wanted the latest hairstyle, turning the barber shop into a paradoxical site: a place geared to current trends, but one that conjures beloved memories. The last two lines are also mirror-like in the way they reflect each other, yet there’s a difference between them, like the difference between ourselves today and ourselves tomorrow, or between a poem and its translation.

*

Note

1John Ashbery, “This Room,” in Your Name Here (Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2000) p. 3. For more examples of shifting tenses in poems, see James Longenbach, “Feeling Tense,” The Kenyon Review 34, no. 4 (2012): 54–68.

2Jo-Wang Lin, “Time in a Language without Tense: The Case of Chinese,” Journal of Semantics, Volume 23, issue 1 (February 2006): 1–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffh033.

3Wai-lim Yip, Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres, 2nd edition, revised (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), xiii-xiv.

4Susanne Katherina Langer, Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953), 267.

5George T. Wright, “The Lyric Present: Simple Present Verbs in English Poems,” PMLA 89, no. 3 (1974), 566.

6Emily Dickinson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. ed. R. W. Franklin. (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 204.

7Stephen Owen, An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1996), 284.