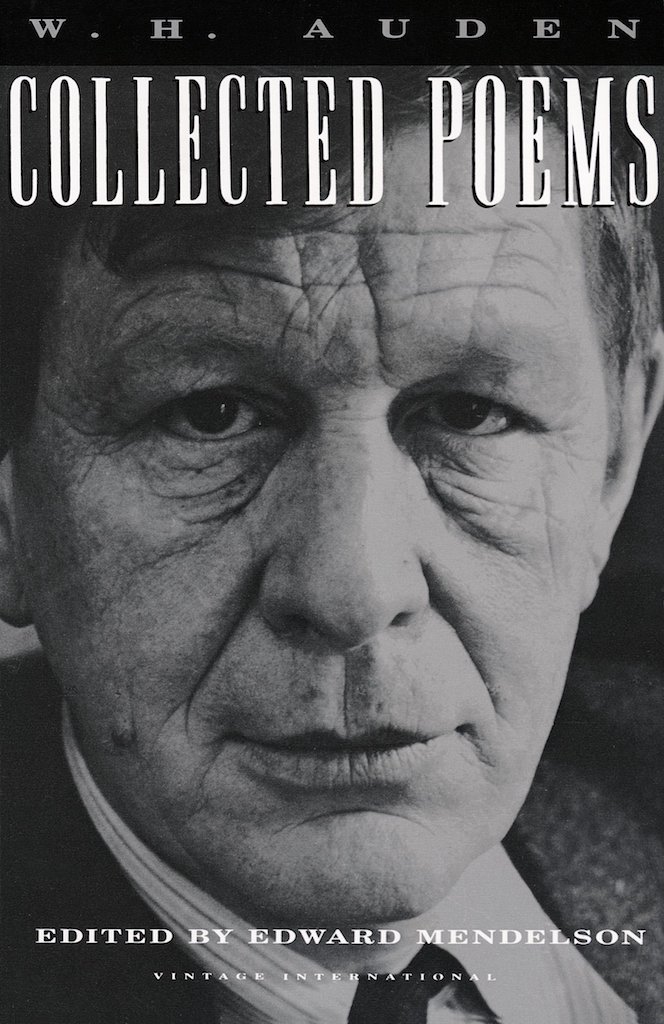

The first time I encountered W. H. Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts” was in my tenth grade English class. I was—to put it mildly—blown away. I let the poem wash over me, and while I lacked the language for both the impact of the poem and the way it achieved those effects, I knew I wanted to stay with the poem and read it over and over again. I have long been afflicted with an obsessive attention—wanting to watch the same film over and over again rather than exploring a director’s full oeuvre, and rereading the same book repeatedly rather than finding the rest of an author’s work. I found myself obsessed with this poem. The rest of the anthology fell away.

Now I think I can articulate what drew me in. Auden is a master of the first line. “About suffering they were never wrong” is rhythmically dense but sonically light. There are two very strong stresses

About suffering they were never wrong

But then the line also has two lighter stresses in the middle of the line:

About suff | ering they | were nev | er wrong

Auden begins the line with two anapests and ends with two iambs, the light tripping of the first two feet speeding up in the tighter rhythm of the second two feet. A slightly Yiddish or Slavic intonation is at work, inverting the expected order of the prepositional phrase and the independent clause (the expected English word order would be “They were never wrong about suffering”). The syntactic inversion is intensified by the naming of the subject at the start of the next line “The Old Masters,” the antecedent following the pronoun in a violation of the decorum of English Syntax.

I remain amazed by how many rules the poem seems to break. The first stanza of the poem is a direct violation of that old dictum, “show don’t tell.” Auden makes a lot of claims about how the Old Masters depict suffering, and he tells the reader how to interpret the paintings being discussed. The Old Masters might be showing, but Auden is quite definitely telling. The fourth line of the poem, in violation of expectation, more than doubles its stress and syllable count:

While some | one else | is eat | ing or op |ening | a win | dow or | just walk |ing dul | ly along

That’s TEN stresses! In TWENTY TWO syllables! In one line! The coherence of the line comes from the iambs, and the two anapestic substitutions give it a bit of a thrill. I didn’t have the language to describe this then, but I could feel both the violation of the expectations created by the line and the confidence of the rhythmic pattern pushing against the intonation of the sentence.

I also loved how self-consciously the poem also follows the structure of an argument. The thesis is in the first four lines, and Auden uses the paintings to prove his point. The descriptions tend toward the periphery of the narrative, and “the dogs go on with their doggy life” may be the most brilliant and charming use of repetition I’ve ever encountered in a poem. In the second and final stanza, Auden introduces the painting of Icarus with “for instance,” clarifying his argument.

Perhaps the least interesting thing to me about the poem was Icarus himself, and never having seen the painting, I didn’t know until a good ten years later that the Breugel painting is actually quite funny. Icarus is a minor detail, his two small white legs sticking out of the ocean, the drama of the fall essentially over. At the time, I imagined a painting centered on Icarus, contorted in agony mid-fall, which made me misread this line: “the sun shone / As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green / Water.” For days, I couldn’t sort out the syntax, and finally I concluded that the painting must portray the sun as having white legs, and that the legs were somehow embarrassing, because the sun didn’t want to stand on them, but “it had to.” I knew enough about Breugel that a grotesque and anthropomorphic sun might be found on his canvases. I knew that something was wrong with my reading, and perhaps I was projecting my embarrassment onto the sun, but I also knew that I loved the poem without being able to understand part of it, and that, absent meaning, it was the sound I loved. Almost thirty years later, as I continue to return to this poem, I find that I’m still attached to that non-existent sun standing on white legs, wading in a green ocean, presiding over a falling boy.