When Reginald Dwayne Betts writes about his time in prison, he is actually writing about the aftermath. He is writing about the consequence of a consequence–a cycle of “disappearing years” against a relentless fight for radical honesty. His life–with all its mistakes and redemption–is whole.

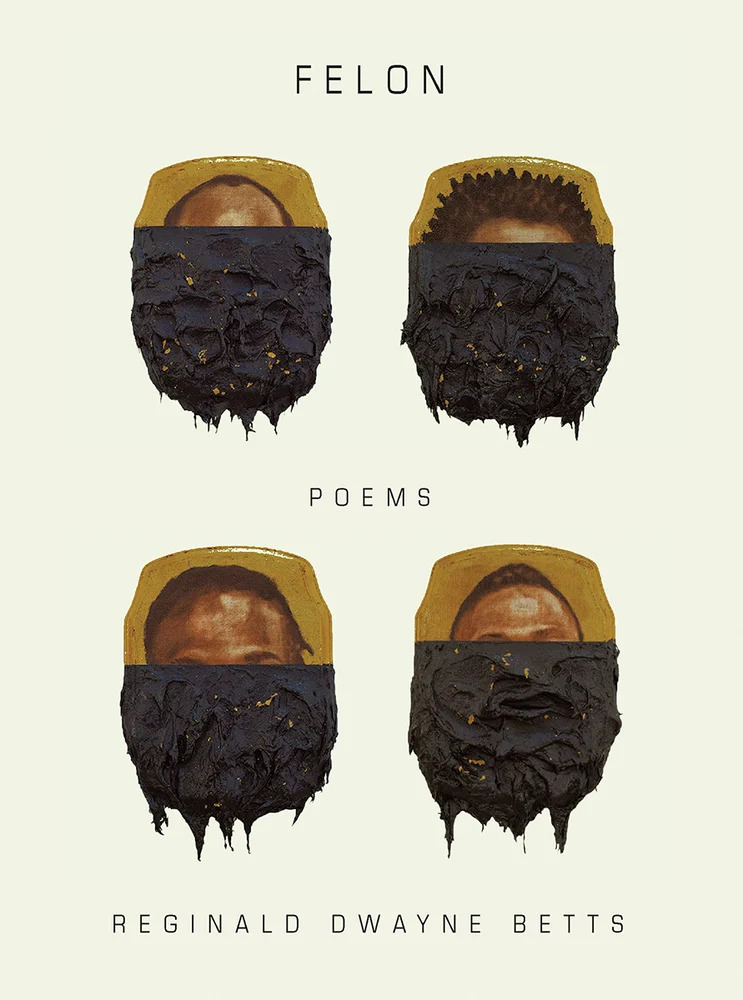

At 16, Betts was arrested for carjacking. He was tried as an adult and imprisoned for nine years. Working with pen and paper behind bars made him a writer. Then, an activist and a public defender. And a husband. And a father. When exploring the impacts of mass incarceration on American society he does not dismiss these multitudes. Instead, the poems in Felon reveal how the many facets of his identity are all weighed down by the words that follow him everywhere–“prisoner, inmate, felon, convict.”

So then he drinks. He loses love. He disappoints his friends and his sons. He fights for his clients but does not always succeed. And this is in part because time in prison doesn’t end there. In this country, it carries on when you try to re-enter society – the “threat that circles.” Betts does not hide just how high the odds are stacked against him, just as he does not hide what he has done.

He claims the label prison gives him–felon–and says, look, I did make mistakes, and now I am dealing with the consequences. But look, also, at how we lend ourselves to the system. How we dehumanize the incarcerated man. How every time he tries to love, we remind him of when he didn’t –“What name for / this thing that haunts, this thing we become.”

This book is for Betts, of course, but also for his cellmates, his clients, his sons, and the Black men like him caught up in the binds of mass incarceration. Betts does not hide just how high the odds are stacked against him. Instead, he shows us how he is freed by his truth and how he finds joy even through the consequences. The system can hold him as a felon even once he is freed. But as these poems show, he is so much more.