Sparked by Translation or How to Write Classical Chinese Poetry in English

The most influential genre of Classical Chinese Poetry is called ‘regulated verse’ (各路诗), and these forms were thought to gather the world into words and refold them into inter-resonant patterns on a cosmological scale. Each monosyllabic word must be stacked in relation to the one before and after, above and below until the whole rests upon a final balanced point, as relaxed and exact as a cairn of transparent quartz.

While the prosodic patterns of regulated verse arrived in China from esoteric Buddhism in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, they increasingly became integrated into pre-existing Classical Chinese “inter-resonance” cosmology (with concepts like yin and yang and five-element theory). By the time of the late Tang Dynasty, regulated verse patterns were integrated into the Imperial Examination system and this form of poetry became a public mirror for aspiring government officials to demonstrate their ability to balance and harmonize the substrate of human consciousness and society (文, language) with the patterns of nature (道,Dao/Tao). For well over 1,500 years, one’s ability to compose regulated verse became an important gateway into a career in the imperial bureaucracy.

While English poets have long been inspired by the concise imagery of classical Chinese poetry, we have not attempted to stack English words following the ancient patterns of parallel and antithetical inter-resonance ascribed by Classical Chinese regulated verse. It has been assumed that regulated verse can only be written in Chinese, but this is not true because what we call “Chinese” is really a large family of many dozens of distinct languages, all of which can be used to compose regulated verse. Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese (Sino-Japanese, Sino-Korean, and Sino-Vietnamese) were adapted over the centuries so that poets in these language worlds could compose Classical Chinese regulated verse as well. At the end of the day, regulated verse forms require a storehouse of monosyllabic words (with the exception of Japanese which found its own interlanguage hack) and it turns out that English has the largest vocabulary of monosyllabic words after Chinese, and thus “Sino-English” is an ideal medium for these forms.

Sparked by Translation: I began experimenting in English-Chinese interlanguage poetry and poetics as a Chinese major at UC Berkeley in the 1990s, when I served as a “STP” (Student Teacher Poet) in June Jordan’s “Poetry for the People” program. Jordan first gave me the assignment to find a way to reveal the music of Classical Chinese poetry in English and over the course of a winter break, I produced my first prototypes which we taught at Cal, and regional high schools, homeless shelters, and prisons. Over the next twenty years, I continued to develop the systems by translating a wide range of Classical Chinese poetry into rhyming, tonalized English monosyllable verse following a syllable-to-syllable methodology and simply adding Chinese tones to the English vowels:

客 舍 青 青 柳 色 新

kè shè qīngqīng liǔ sè xīn

guèst ìnn greēngreēn wǐl lòw sheēn

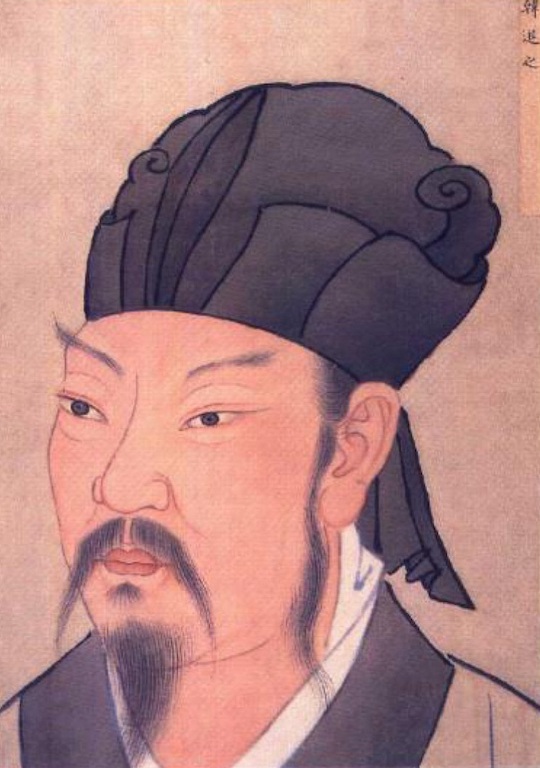

The seeming magical resonance between English and Chinese could work in rare moments of interlanguage serendipity, but in most translations I had to change the word order within lines in order to reproduce the original’s prosody in English. Here is an example of these early translations, a Sino-English translation of “Spring Snow” by the poet Han Yu (韩愈)

春 雪

新 年 都 未 有 芳 花

二 月 初 驚 見 草 芽

白 雪 卻 嫌 春 色 晚

故 穿 庭 樹 作 飛 花

Chūn xuě

xīn nián/ dōu wèi/ yǒu fang huā

èr yuè/ chū jīng/ jiàn cǎo yá

bái xuě/ què xián/ chūn sè wǎn

gù chuān/ tíng shù/ zuò fēi huā

Spring Snow

nēw yeárs/ cōmes bùt/ bloǒms dōn’t grōw

Màrch neàrs/sūr-prīsed/ gràss sprǒuts grów

yét whǐte/ snòw thínks/ sprīng’s còme lǎte

ànd fālls/ thróugh treès/ lìke blōoms blōw

While it may appear that we are looking at a translation that matches word meanings to word meanings, we are not. Instead, the translation is based on matching the meaning of each line, but the translation is re-inscribed into “Sino-English,” which retains the original’s tonal prosody so that one can chant the English version as if it were another dialect of Chinese.

Over time, I moved away from translating existing poems using this method, to further explore the possibilities of composing original verse. With over 5,000 monosyllable words to play with, it is possible to reconstruct a viable life world for regulated verse culture and its poetics in English. To accomplish this end, I have mostly focused on the genre known as “jueju” (a poem of four lines of five or seven monosyllable words), and developed the genre with three levels of difficulty: The first is modeled on “ancient style jueju” (古体诗), while the other two are inspired by the “regulated” genre of “recent style jueju” (新体诗). The later two categories incorporate parallel and antithetical prosodic and semantic rules. For the sake of this writing prompt, I will introduce only the first level (ancient style) jueju, but I encourage everyone to try their hand at the more complex “recent-style jueju” as they can be the most rewarding.

In 2011 I created the Newman Prize for English Jueju at the University of Oklahoma (in conjunction with the Newman Prize for Chinese Literature) which awards $500 to the best English jueju in four categories: Elementary School, Middle School, High School, and College/Adult and this year the competition is open the UK as well. You will find all of the resources (games, rules, vocabularies, and writing prompts) and rules for the regulated jueju forms here:

https://link.ou.edu/english-jueju

https://link.ou.edu/english-jueju-resources