“Time was honey,” and I was mostly not sleeping when I read Hillary Gravendyk’s Harm in March 2020, through a fever, at the beginning of the pandemic, and again last month as the mask requirements eased up and many of us with chronicities and/or (dis)abilities exchanged messages with “worry buried in the folds” and daily found ourselves inside a surreal silence while outside the parties and chatter moved fast. Faster—“A bright story is requested.” Instead, we juked the official narratives in our private speech. We piled our excuses up.

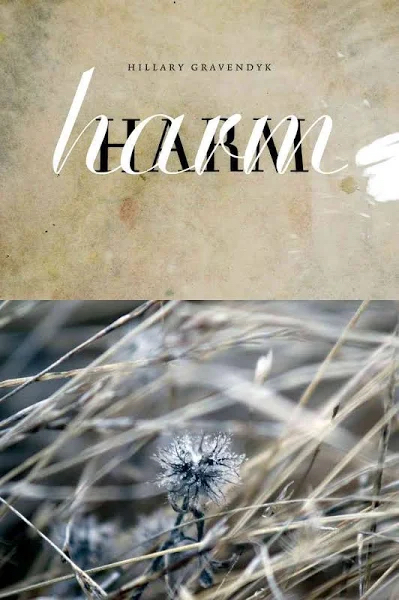

Harm—published in 2011 and written after Gravendyk’s double-lung transplant—wrests up many unofficial occasions of sick bodies, both human and more-than-human, by irregular pulse beats in quietly tensile prose poems and lyrics. While the poems are alert to, and pained by, threats internal and external, they refuse to resolve themselves to dire clinical measures of the person. If the body is “starred with damage,” marked by invasion, error, and anxiety, in its terrifying openness, it also becomes speculative matter, tendering a pathway into alternate pasts and presents.

Through embodied matters, “dark alphabets” and unspeakable grammars spool out entire landscapes of felt significance. “There’s a night inside the night in my chest.” Harm asks us at times to float through long, telescoped corridors of such nights, past “nested rooms” of exposure and embarrassment, at others to simply close our eyes in the waiting rooms of the clinical, and capital, and lie down next to the sleepers of these poems, their bodies “sutured to harm,” where we might listen in at the level of the molecular.

At this level, presence thickens with mute signs, barely audible signals, and oscillating intensities—”quarter-light,” grass-whorl, kisses, traffic, or just “the shush of machines flickering on.” This vocabulary beyond—or, really, before—the word expresses vital transgressions and interdependencies between human, mineral, animal, and machine. In Harm’s clinical theater, each occasion of expiration and increasingly tenuous inhalation is inextricable from a shared, transspecies precarity. That precarity isn’t the (dis)order of only the acute or chronically ill: it is here evoked both as a general condition of beingness and as the ongoing consequence of clinical and capital invasions in an era of irreversible ecological damage. “In the slippery groves of the chest another sleep ratchets closer, yellow with significance, clouded with ash.”

And yet.

I want to say, am failing to say, how astonishingly bright it is: through Harm, you can yet trace the spine of islands on someone’s back, travel a syllabic string, get that kiss, hear the “pink singing” threading itself through every room, glow with listening, make a naked escape even when the “limbs [fill] with sand.” I keep reading it because it makes me desire its inevitable cyborgs and monsters, its palpitated time-signatures, its “pink dreaming riot.” I, too, want to get weaved in. Or—I am already weaved in, and desire a present, and future, that is livable with, and inclusive of, a chronic error-measure. Give me less of that narrative “cure” imposed “across an abrupt jumble of absences” and more of this speculative wildness.